Why we keep our loved ones’ old clothes

In the first room of Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child – an exhibition looking at the final chapter of the great French-American artist’s career, currently at London’s Hayward Gallery – there stand a set of doors. They are huddled together, forming a small, room-like space. Their surfaces reveal their age. The wood is faded and splintered. Glass panels hold webs of cracks. Inside, arranged on a series of metal armatures and fat, yellow cattle bones, there hang a series of undergarments: slips, shirts, chemises. The fabrics are feather light against the heavy bones. They betray signs of their storage, crumpled and imprinted with creases from decades of being folded away. On the floor there lurks a watchful metal spider. To one side there sits a model of Bourgeois’ childhood house in Choisy-le-Roi. To the other there is a spiral staircase, threads spooling out from the top and tethering it to these still, white clothes.

More like this:

– Literature’s greatest fashion disasters

– The woman written out of history

– How Paula Rego helped change the world

Entitled Cell VII, this installation was created by Bourgeois in 1998. In the last two decades of her life – which is the period the Hayward Gallery show covers – the prolific artist turned to textiles. Or rather, she returned. As a child she watched her parents mend and trade antique tapestries, her mother repairing them and her father selling them in a gallery in St Germain, Paris. Sometimes Bourgeois helped out, drawing in the missing parts of scenes – often feet, which were the first to wear away because they were at the bottom of the work – but she wasn’t initiated into the intricacies of needlework or weaving.

Louise Bourgeois’ 1998 installation Cell VII features a series of undergarments many of which belonged to her mother (Credit: Hayward Gallery)

She did, however, go on to live a life haunted by fabric. Clothes were a source of great joy and even greater friction. As quoted in Charlie Porter’s What Artists Wear, in 1968 she wrote in her notes, “it gives me great pleasure to keep my clothes my dresses, my stockings… It’s my past, and as rotten as it is I would like to take it and hold it tight in my arms.” Later she would describe these possessions as burdensome, representing “failures, rejects abandoned.” In 1995, she finally managed to let them go, transferring most of her clothes to her studio where she could turn them into raw, sculptural material. She commented on the weight that had been lifted: “the cord was cut and I felt dizzy – the history of the wardrobe had started”. It’s an image that simultaneously evokes birth – the umbilical cord – and death – the cord akin to the thread cut by Atropos, the third Fate of Greek mythology tasked with deciding life’s end point.

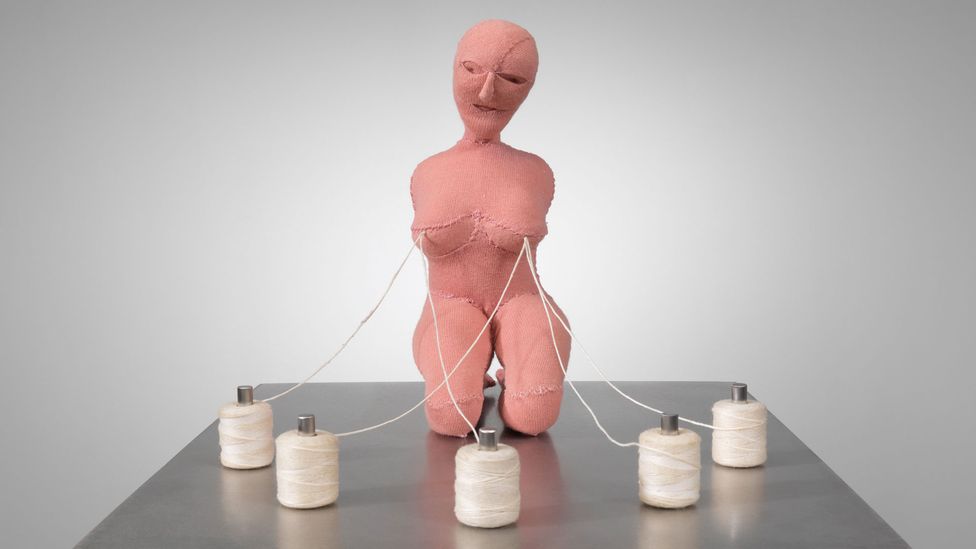

This “history of the wardrobe” shaped the closing chapter of Bourgeois’ long career. Many of her textiles, which also included household napkins and linens, were cut up and turned into sculptures and artworks: contorted faces, cloth books, lumpen bodies constructed with exposed seams like scars. Others were kept as they were. Items from her youth – black cocktail dresses, pink silk coats, pale blouses – became mementoes of previous selves, hanging freely or stuffed and sewn closed to suggest a human form. She conjured family members too, invoking them by the clothes they had once worn. Many of the garments in Cell VII belonged to Bourgeois’ mother Jósephine, who died when Bourgeois was only 22. Jósephine was the symbolic spider who hovered over her anxious, furious daughter, an emblem of protection and methodical repair.

Katie Guggenheim, assistant curator of The Woven Child, sees Cell VII as an eerie assemblage. “They’re intimate clothes – night clothes – and they’re ghostly in the way they float… Like nightmares [or] apparitions,” she says, surveying the thin fabrics.

Clothes are often referred to in ghostly terms, which is unsurprising given their appearance. Suspended, they take on a spectral guise. Like ghosts, they also hold echoes of the dead. Garments outlive their owners. In their presence, they allude to an irrevocable absence. As the academic and author Peter Stallybrass writes in Worn Worlds: Clothes, Mourning and the Life of Things, an essay on memory and a much-loved blazer, “in thinking of clothes as passing fashions, we repeat less than a half-truth. Bodies come and go; the clothes that have received those bodies survive.”

Bourgeois is not the only artist to have been moved by the survival of clothing beyond mortal flesh. Nor is she the only person who has felt both the solace and burden of garments too heavy with meaning to easily dispense with. In life, our clothes are incredibly personal. They enfold us and keep us warm. They signal our jobs, our tastes, the ways we want to be seen. In death, they become tactile reminders of what once was, made to fit bodies that can no longer fill them.

Mourning rites

The heavy scent of perfume. A half-stirred memory of a dress worn on a summer’s day. The prickling texture of a jumper, rubbing against skin. At once mundane and tactile, clothes are extraordinary vessels of memory. This is what gives them their power at the point of death. They retain the most intimate parts of ourselves: our smell, our sweat, evidence of our presence (scuffed toes, worn down elbows). When an artist chooses to use clothes belonging to someone they loved, they make that intimacy public.

In the final part of her career, Bourgeois used her clothes and miscellaneous textiles, such as household linens, to create sculptures and artworks (Credit: Hayward Gallery)

In 2016, the Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey embarked on a project titled My Mother’s Wardrobe. Two years after his mother died, he walked the streets of Accra in one of her patterned dresses, a bag of hers slung over one shoulder. He was joined by other men from his GoLokal art collective, also dressed in clothing belonging to their mothers. It wasn’t just a grief ritual or personal act of remembrance, but a riposte to tradition. In Ghanaian culture a mother’s possessions are often left undisturbed for a year after her death before being distributed among daughters and other female members of the family. Attukwei Clottey, an only son, wanted to claim them instead for himself. Later he worked on a photo series that further cemented the significance of this inheritance, standing quietly in her gowns and posing with the elaborate kente cloth that was used to cover her coffin.

Why do we want to hold onto the clothes of the dead, to wrap ourselves in them? It is, in part, a simple act of possession. Death is the cruellest vanishing act. Someone who was once here, filling the room, transforming it with their presence, is gone – and nothing can bring them back. But that is not to say that they have entirely vanished. Traces linger. Sometimes they are unbearable. In grief, a person might find it impossible to go near a wardrobe, or want to throw everything out immediately in order to lessen the pain (one thinks of Simone de Beauvoir writing in A Very Easy Death, her account of her mother’s death from cancer: “they found Maman lying on the floor in her red corduroy dressing gown… I never want to see that dressing gown again”). But keeping such items close, even putting them on, offers both a form of reclamation – a thread of connection between the living and the lost – and a promise of continued existence.

Authors understand this complicated afterlife of objects. In the moving middle section of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927), a chapter marked by the relentless march of time, a number of characters die. Woolf places their deaths in brief parentheses. The passing of matriarch Mrs Ramsay is described thus: “Mr Ramsay, stumbling along a passage one dark morning, stretched his arms out, but Mrs Ramsay having died rather suddenly the night before, his arms, though stretched out, remained empty.” The real emptiness though is described in the clothes “shed and left” in their holiday home. “For there were clothes in the cupboards… They had the moth in them – Mrs Ramsay’s things. Poor lady! She would never want them again.” A mother’s death is made concrete in her abandoned clothes, in their slow degradation. That is where the real, aching emptiness of loss resides.

It’s notable that in Bourgeois’ Cell VII, the clothes remain intact. Elsewhere the exhibition is full of mutilated materials. Things are cut, stitched, stuffed, frayed, patchworked and repaired. Coats gain tails. Hook and eyes form angry circles. A cluster of red fabric legs dangle from the ceiling. But her mother’s clothes seem sacrosanct. Hanging there in their own little room, they remain untouched – as though Bourgeois could have reached in and taken them down from their cow bones at any point, gathering them in her arms once more. However, decay is present even here. As Katie Guggenheim observes of the work, “because they’re textiles, they are very fragile. You can see these have yellowed. They’re not marble. They’re vulnerable fabrics. They are ageing… like second skins.” Clothing extends time, but it doesn’t freeze it. We can’t hold on to anyone forever.

What could have been

The choice to use or invoke a mother’s clothing feels especially charged with meaning. It suggests the physicality of parenthood: a world of breastfeeding and being held, of kissed foreheads and reassuring hugs. In wearing or working with such garments, an artist turns tangible memory into a relic, offered up for others to see. However, another kind of meaning emerges when clothes are stripped of individual biography. For every garment held onto by a loved one, there is another that has been sent back out into the world shorn of its stories.

Serge Attukwei Clottey’s project My Mother’s Wardrobe saw him walk the streets of Accra wearing one of his late mother’s patterned dresses (Credit: Nii Odzenma/ Gallery 1957)

Often when looking at a vintage jacket or old handbag, one is prompted to picture its previous lives. In a piece in the collection Sketches by Boz (1836), Charles Dickens describes wandering through the second-hand clothes market found on Monmouth Street in London. He characterises it as a “burial place of… fashions,” and a space where “wandering through the extensive groves of the illustrious dead” one might indulge in speculation: “now fitting a deceased coat… and anon the mortal remains of a gaudy waistcoat, upon some being of our own, conjuring up and endeavouring, from the shape and fashion of the garment itself, to bring the former owner before our mind’s eye.” In the world of worn clothes, spectres of former owners are never far away.

Rozanne Hawksley’s Pale Armistice (1987) is a startling funeral wreath. It is composed entirely of white gloves, in every fabric and size. Some are for children. Others for army officers. Cheap nylon suggests a wedding. Soft suede mimics skin. Made to commemorate the losses of World War One, Hawksley’s work uses clothing to suggest a vast number of possible lives and narratives. Gloves are an effective accessory for this kind of exercise, given how closely they resemble the hand they are made to clad. Looking at the wreath, it’s easy to imagine the fingers of a dead soldier or a bride with no one to marry. When discussing the piece, Hawksley spoke of the dual function of the hand as something that brought both kindness and cruelty. A hand can hold a child or aim a gun. Jumbled together, thick layers of gloves conjoined and overlayed with artificial flowers, those meanings become fused into one, tragic whole.

In their anonymity, clothes have this incredible capacity to evoke life – and death – on a vast scale. Christian Boltanski, a French sculptor, spent much of his life making huge memorial-style pieces. He filled rooms and corridors and warehouses with clothes, using them as stand-ins for the people who had once worn them. In an interview for his 1997 monograph, he explained their power: “What is beautiful about working with used clothes is that these have really come from somebody. Someone has actually chosen them, loved them, but the life in them is now dead. Exhibiting them… is like giving the clothes a new life – like resurrecting them.” These resurrections have yielded many interpretations. Among other things, there are powerful post-Holocaust implications, many of his pieces drawing inevitable parallels with museums and memorials that have retained the possessions – especially the shoes – of those who were murdered in concentration camps including Auschwitz and Majdanek.

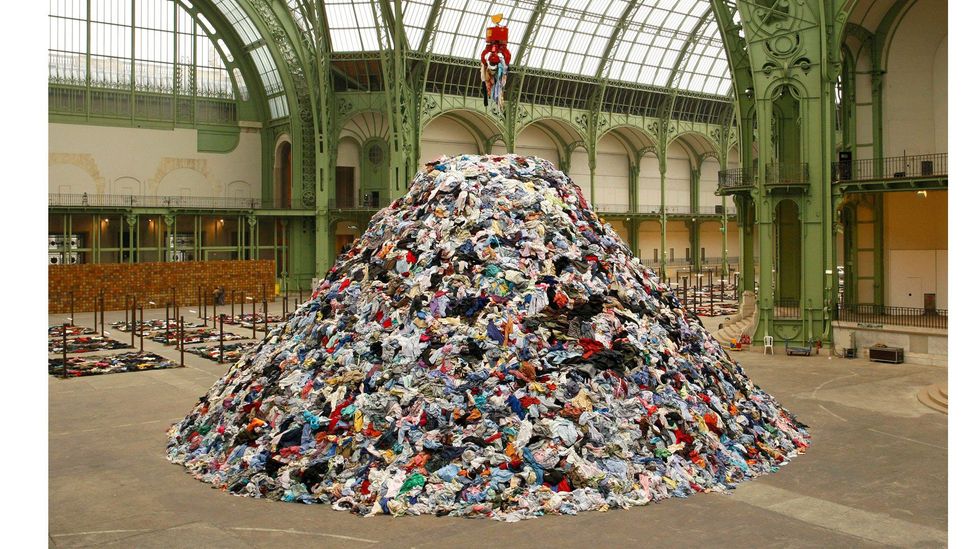

Sometimes, though, the meanings are less straightforwardly legible. For a 2010 piece titled Personnes, Boltanski filled the Grand Palais in Paris with 69 piles of clothing. Laura Cumming, in an echo of Dickens, wrote in her review for The Observer that they were reminiscent of “mass graves, or… a kind of cemetery”. Overhead a metal claw roamed, picking from the clothes at random and depositing them in a central pile that came to resemble a mountain. The only sound in the space was a recorded loop of heartbeats. Here, it was suggested, lay unknown legions – every garment symbolising a person, becoming a souvenir of an entire life. His only regret, he later said, was that they didn’t have a stronger smell. He wanted them to overwhelm the viewer with evidence of those absent bodies.

Telling stories

On the wall near her mother’s clothes in the Hayward Gallery, there is another quote from Bourgeois: “These garments have a history, they have touched my body, and they hold memories of people and places. They are chapters from the story of my life.” A history of a person is a complex thing, whether one is recalling their own life or that of someone they were close to. Like a gown inherited after death, often these histories are subject to competing claims of ownership. We all have our own accounts, our particular interpretations of events and relationships. No wonder, then, that garments have the capacity to hold so many feelings at once: love, ambivalence, grief, resentment, yearning, comfort, unease. In becoming extensions of ourselves, they end up taking on all of our own complications.

The French sculptor Christian Boltanski made huge memorial-style pieces filling rooms and corridors and warehouses with clothes (Credit: Alamy)

There are many ways to tell the story of a life. In using personal items to deal with the intricacies of loss, an artist often finds themselves committing an act of preservation. Bourgeois’ clothes are no longer just clothes. They are part of an installation, treated with the same level of reverence and care as an oil painting or a statue in a museum. The truth is, no one could now take down Jósephine’s slips and feel the fabric beneath their fingertips. Only a select few archivists wearing their own protective layers are allowed to handle them. As Katie Guggenheim explains, “they are handled like the most precious thing in the world.” Reassembly is a finely tuned process, full of slow movements and padded tables. She sees their signs of storage as both literal and symbolic evidence of the passage from possession to creation. “Those folds represent the time they were waiting in between being lived clothes and being artworks.” Cell VII alludes to mortality and memory, but in making it, Bourgeois changed the very meaning of the garments featured.

In using textiles to evoke any number of possible lives now forgotten, an artist engages the imagination. Here there are no dates or details. Instead, piles of trousers and coats or wreaths of gloves invite us to look closer and envision the bodies that once touched them: the hands they passed through, the situations they saw, the drawers and wardrobes they slept in. Such pieces might function as resurrections, but they also demand creative reconstruction. All we have in front of us is cloth. Cloth that was designed, shaped, cut and stitched into something fit to wear. We must speculate for ourselves what kind of life it could conceivably have held.

Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child is at London’s Hayward Gallery until 15 May

BBC Culture has been nominated for best writing in the 2022 Webby Awards. If you enjoy reading our stories, please take a moment to vote for us.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.