What to do with decaying masterpieces?

When sculptor Naum Gabo made a pioneering series of sculptures in plastic back in the 1930s, he was following the fine artistic principle of experimenting with a then-new material offering an intriguing combination of transparency and flexibility. What Gabo couldn’t know was that his chosen material would warp and crumble over the ensuing decades. Today, sculptures like Construction in Space: Two Cones (1937) lie in fragments, consigned to store-rooms at galleries such as London’s Tate Modern. “It’s sad,” says Bronwyn Ormsby, senior conservation scientist at Tate. “But all we can do is analyse it, and if it’s gone, it’s gone.”

More like this:

– A chronicler of US turbulence

– The artist who likes to blow things up

– How fear shaped ancient mythology

There’s a common idea that museum artworks are somehow timeless objects available to admire for generations to come. But many are objects of decay. Even the most venerable Old Master paintings don’t escape: pigments discolour, varnishes crack, canvases warp. This challenging fact of art-world life is down to something that sounds more like a thread from a morality tale: inherent vice.

Naum Gabo’s Construction in Space: Two Cones (1937) was constructed in a material that was pioneering at the time – but which proved not to endure (Credit: Naum Gabo/Tate)

Responding to the inherent vice that destroyed Gabo’s sculptures, a gallery might, of course, consider using old photos and other documentation to make as-new plastic replicas of Gabo’s “dead” sculptures. But wouldn’t they just be fakes – albeit fakes made by the institution that owns what’s left of the original? It’s a topic of heated debate, with galleries mulling over ethical issues around authenticity, loss and conservation. “Though we got as far as creating 3D digital models to have replicas made,” admits Ormsby.

Damien Hirst’s iconic shark floating in a tank – entitled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living – is another work that put a spotlight on inherent vice. When he made it in 1991, Hirst got himself in a pickle by not using the right kind of pickle to preserve the giant fish. The result was that the shark began to decompose quite quickly – its preserving liquid clouding, the skin wrinkling, and an unpleasant smell wafting from the tank.

Despite its increasingly sorry state, the piece was bought for several million dollars in 2004, which was when Hirst decided to try and sort out the problems. His first attempt to salvage the work involved skinning the shark, tanning its hide, then draping it around a shark-shaped fibreglass frame. Unfortunately, this made an object intended to evoke metaphysical dread look more like a cheap prop at a Jaws convention. Eventually, Hirst remade the sculpture from scratch with a fresh shark plus expert input from preservation experts at London’s Natural History Museum.

Hirst’s shark, or The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), had to be replaced in 2004 as it hadn’t been preserved correctly (Credit: Getty Images)

Other artists help museums tackle issues around inherent vice by encouraging the remaking of work right from the start. Sculptor Tom Claassen, for example, regularly helps conservators redo his works made from highly degradable rubber. Ditto Janine Antoni’s work Gnaw at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) gallery – a giant cube of lard and another of chocolate, sculpted with the artist’s teeth – which is recast afresh every time it goes on display, using moulds she has provided based on her bite.

Freedom to challenge

Yet many artists continuously throw down a gauntlet to museums by making work in tricky materials like soap, blood and faeces. In the 1960s, MoMA decided not to buy a Robert Rauschenberg sculpture due to worries about vermin – a fair concern for an artwork whose central element was a stuffed goat.

Or how about the ground-breaking 1960s works of Swiss artist Dieter Roth, made from food stuffs such as cheese and sour milk? His work Basel on the Rhine, meanwhile – owned by MoMA – was made by painting chocolate on to steel plate. MoMA’s website describes matter-of-factly how the work has changed since its acquisition, thanks to the inherent vice of its materials: “Over time, the chocolate has cracked, developed a bloom (a thin, whitish layer of fat), and been host to tiny insects, as evidenced by the small holes covering the surface”.

MoMA has opted for what it calls “passive conservation” by keeping the piece under glass, and trapping bugs when they are spotted. By contrast, the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts Lausanne in Switzerland is leaving its Roths to decay as fate decides, even though it recognises that eventually they will join Gabo’s crumbled plastic sculptures in the cultural afterlife where “dead art” goes.

Anselm Kiefer has said that “maybe a work is only finished when it’s ruined” (Credit: Getty Images)

Painter Anselm Kiefer is another who messes with the heads of museum folk. His monumental canvases have included electrodes that cause metallic oxidation to spread wildly across their surface, while other canvases are sent to galleries in full expectation that bits of them will fall off in transit. “It is not so easy having a painting of mine,” Kiefer noted wryly in a 2009 interview for The Independent.

Mechanical breakdown, meanwhile, is a conservation challenge for art with moving elements – called kinetic art. As wear and tear impairs moving parts, museums are faced with deciding whether to “retire” works before they get too damaged.

A case in point was when the Centre Pompidou in Paris decided in 1988 to stop the movement of Jean Tinguely’s 1954 kinetic sculpture Méta-mécanique automobile. It was a decision that left Tinguely unruffled, as he explained in a 1984 interview: “My works are not intended for eternity, they’ll wear themselves out and land back on the garbage heap whence they came”.

Breaking down

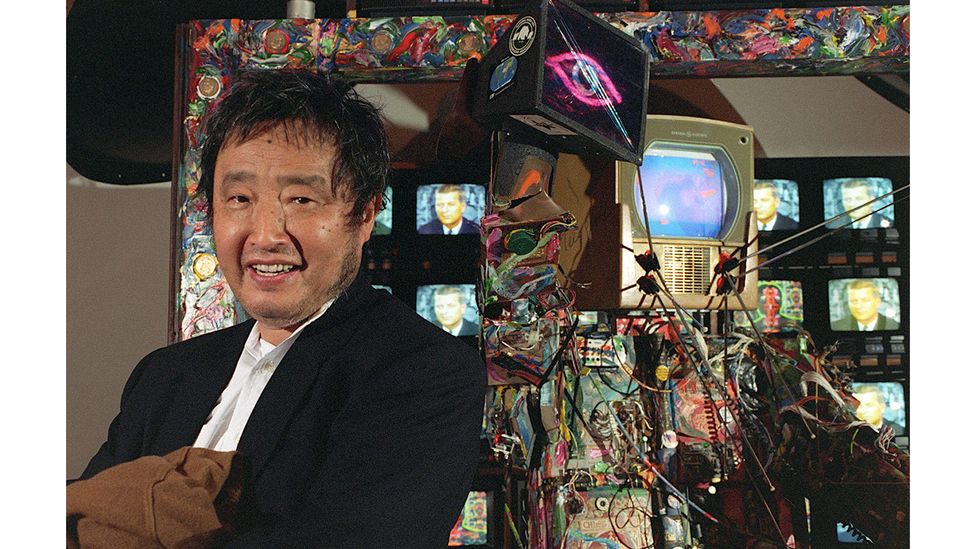

The growing trend for technology-based art works – often grouped under the title Time-Based Media – can also create problems for museum experts. Take Nam June Paik’s seminal 1980s work Video Flag Z in Los Angeles County Museum of Art – a kaleidoscopic wall of 84 old-school cathode-ray tube (CRT) TVs, whose fuzzy pictures are integral to the work. But what do you do when the vintage TVs inevitably start breaking down?

At first, curators simply scrambled to try and buy old CRT sets, but as supplies dwindled, the only sustainable solution to displaying the work was to make new sets that “look like” the real old ones (done with the agreement of the artist’s estate). Rather than glorified fakes, museums prefer to call responses like this “emulations”, aimed at presenting the essence of the artwork – playing against the traditional status of a unique “original”.

South Korean-American artist Nam June Paik, who died in 2006, is considered to be the founder of video art (Credit: Getty Images)

Some artists working in time-based media try to ease the conservation stresses on museums. When Tate bought Michael Craig-Martin’s 2003 work Becoming – an endlessly changing computer-generated animation on an LCD screen – the artist provided its source code to help create future exhibitions on whatever displays might be around.

Further challenges are posed by artworks based on live performance. Pip Laurenson, Head of Collection Care Research for the Tate, explains how Tate Liverpool approached a 2019 display of Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, a live film and musical work by Tony Conrad, which existed only as a string of individual performances since its 1972 debut in New York.

“Although we started conversations with Conrad when he was still alive, the work was acquired after his death. He didn’t like producing scores, so he taught performers what to do each time it was staged,” she explains. “So we collected people’s accounts of performing it, and learned what aspects needed to stay the same and where there was scope for improvisation and interpretation.”

This broadening of the idea of how museums conserve and display art is both a challenge and an opportunity. “It has forced us to rethink what our job and role really is, and in so doing, expand our thinking about what care is and can be,” says Brian Castriota, Time-Based Media Conservator at National Galleries of Scotland.

It’s a living thing

One of the newest categories of art keeping museum curators awake at night is the (literally) growing body of work made with living organisms. How do you conserve and display a work of art that is alive, that can evolve or die?

Take Liz Larner’s works made with bacteria, such as 1988’s Every Artist Gave a Breath. For this, Larner asked fellow artists to exhale on to an agar culture in a petri dish, which was then put on display. Over the exhibition run in the Austrian city of Graz, bacteria in the dish grew into blooms free of any guiding influence from the artist. They then eventually died and turned black.

Another striking example is Simon Starling’s 2006 Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore). This featured a full-scale steel replica of Henry Moore’s Warrior with Shield which was submerged in Lake Ontario for 18 months to slowly become covered by zebra mussels that couldn’t care less if they made their home on a rock or a piece of modern art. The invasion of nature into art took a further twist when the piece went on show at the Art Gallery of Ontario, as it became further infested by moths.

Rauschenberg created Monogram (1955-59) when he was working with stuffed animals – as he said, to “continue their life” (Credit: Alamy)

In museum-speak, these works with living organisms explore interactions between the supposedly sealed and controlled world of an art gallery, and the more uncontrolled reality of nature outside. The artist sets in train a process that creates different manifestations of a work, with the concept being more important than any single manifestation.

At Tate, Pip Laurenson has recently led a major research project called Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, exploring issues Castriota sums up neatly: “The world we’re all a part of is ever-changing – and although keeping an artwork frozen in time may sometimes be a desire, it can also be like trying to hold water in your hands.”

Conservation ethics

Given artworks can be worth huge sums of money, perhaps it’s no surprise the law has weighed into some of the issues around conserving art works that don’t just sit there unchanging – although legislators on either side of the Atlantic have reached different verdicts.

Since the 1880s, Europe’s Berne Convention has defended artists’ right to protect their work from “distortion, mutilation or other modification”. So a litigious artist could in theory judge well-meaning conservation to amount to “other modification” and sue a museum. In contrast, the US Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), passed in 1990, stated that “the modification of a work of visual art which is the result of conservation… is not a destruction, distortion, mutilation, or other modification”. That means conservation can depend not just on available techniques but also on the law or ethics surrounding a repair.

While museum experts fret, perhaps art lovers should just enjoy the interesting and sometimes unintended manifestations of contemporary art, however they are made or displayed. “I would never advise an artist not to use ephemeral media,” says Glenn Wharton. “If art production was driven by durability alone, everything would be carved in granite. What a boring world that would be.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.