The tapestries revealing hidden history

For thousands of years history has been written with a needle, with communities using textiles to preserve their cultural heritage and chronicle their past. In recent times, a number of these projects have taken inspiration from the Bayeux Tapestry, the 11th-Century embroidery depicting the Norman Conquest of England in 1066.

More like this:

– Powerful photos of queer life in South Africa

– Striking images of ignored Americans

– The clothing that reveals hidden truths

One example of this is the Keiskamma Art Project: an award-winning collective of 140 artists, mostly women, working in and around the village of Hamburg in South Africa’s Eastern Cape. Their colossal, hand-stitched work is now the subject of a major retrospective at the Old Women’s Jail of Constitution Hill, Johannesburg. The exhibition Umaf’ evuka, nje ngenyanga / Dying and Rising as the Moon Does brings together two decades’ worth of artworks; their masterpieces flood the walls that once imprisoned anti-apartheid activists including Fatima Meer, Albertina Sisulu and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

In their work, the Keiskamma artists consider all kinds of local experience, from climate change to HIV/Aids, and the struggle for racial justice and gender equality. Pride of place in the exhibition goes to the first chapter in the Keiskamma Art Project’s story: the Keiskamma Tapestry. Completed in 2003, it’s a landmark in community embroidery: one that preserves 300 years of Eastern Cape history across 120m of red-ochre hessian.

At the start we see San bushmen, whose silhouettes echo their depiction in their own ancient rock art. Everyday rural life and Xhosa culture is remembered alongside scenes of colonial invasion and atrocities committed by Dutch and British soldiers in the 18th and 19th Century Frontier Wars. Further down the tapestry, Nelson Mandela is burning his passbook in protest of the Sharpeville Massacre – sewn defiantly next to the “architect of apartheid” Hendrink Verwoerd. Images of torture and resistance, including the Soweto uprising, appear before we see hand-stitched ballot boxes from South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994.

“When we look back we’re sort of reinstating our history for the world to see who we are,” long-established Keiskamma artist Veronica Betani tells BBC Culture.

“The history of Hamburg is also the history of South Africa, with all of its unresolved colonial legacies and difficult epidemic histories,” says the exhibition’s co-curator Azu Nwagbogu. “The resilience and will of the people have been crafted into tapestries.”

The power of the process

When people come together to sew local history, they create a space that can be just as important as the end result. The Keiskamma Art Project began when free embroidery training workshops were opened by the Keiskamma Trust in 2002. Women were paid for everything sewn, numbers grew, and the Keiskamma studio became a hub for studying local history, sharing memories, and weaving those stories into tapestries. Today, Keiskamma arts are a vital source of local income, but visual artist and educator Nobukho Nqaba explains that Keiskamma artists also “share, stitch and write personal and collective trauma – experienced by a majority of black South Africans – as a way of healing.”

“We lost so many colleagues on the road,” says Betani. “Some years back I thought I was not going to make it because I was diagnosed with depression, and then epilepsy. After that, I found out that I’m HIV positive. All those things made me think ‘this is the end of the road’ but it was not. So, I’m the one rising and dying as the moon does.” The success of the Keiskamma Tapestry meant Betani and her colleagues embarked on other commemorative works that also feature in the retrospective, including the Keiskamma Guernica and the Keiskamma Altarpiece. Both reflect on the impact of HIV/Aids in Hamburg. Blankets from the Keiskamma Treatment Centre are appliquéd into the Guernica tapestry, while the Altarpiece sanctifies local grandmothers who cared for their families during the epidemic.

The Keiskamma Tapestry isn’t woven on a loom like traditional tapestries, but its name deliberately invites us to see parallels and contrasts with the Bayeux Tapestry. Thought to be a work of propaganda, commissioned by William the Conqueror’s half-brother, the original Bayeux Tapestry is a subversive choice of inspiration for the Keiskamma artists, who are, by contrast, stitching history that is told for the people, by the people. Little is known of the Anglo-Saxon nuns believed to have made the Bayeux, but the same stem-stitch they laid for the titles of kings was used by the Keiskamma artists to stitch their own names across every metre of the Keiskamma Tapestry.

“History is not just what we see in the news, but it’s our everyday lives,” says Eastern Cape performance poet Lelethu ‘PoeticSoul’ Mahambehlala who collaborated with Keiskamma artists for the aBantu Development Agency’s History Re:imagined project. “When they took us through the work, they were calling all the people on the tapestry by name. These women are authors.”

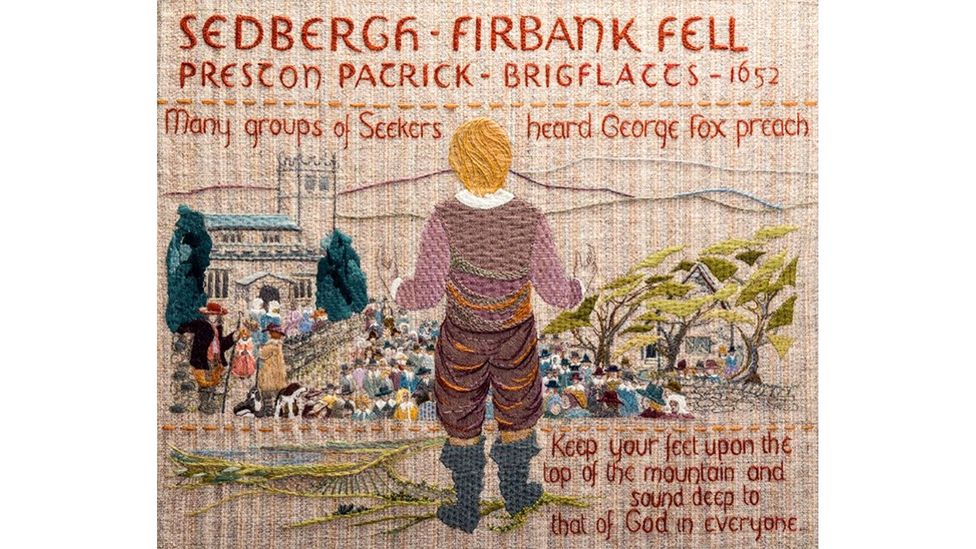

Reimagining history is a common purpose for community embroidery projects inspired by the Bayeux. More than 4,000 people stitched England’s Quaker Tapestry to create a history lesson that doesn’t shy away from the persecution of Conscientious Objectors, The Peterloo Massacre, and the British transatlantic slave trade. In Ireland, the Ros Tapestry reminds us that there’s more to the Norman Conquests than English soil, while The Last Invasion Embroidered Tapestry in Wales brought together women aged 30 to 82 years old to depict French forces landing in Pembrokeshire, Wales in 1797. Like the Keiskamma Tapestry, they echo the Bayeux to say, “our past matters, and so do we”.

The significance of sewing

When we thread a needle and make a stitch we mimic the hands that moved like ours across thousands of years. Keep stitching, and the mind begins to wander: What was whispered between the nuns as they pierced the linen of the Bayeux Tapestry? Did the suffragettes feel the same tension in their wrists as they made banners of protest? The steel between our thumb and finger becomes a little antenna receiving voices from the past as we record our own message for the future.

Looking at history through the eye of a needle is how Clare Hunter’s book Threads of Life explores the social, emotional, and political significance of sewing around the world. Hunter invites us to look closer at the Keiskamma Tapestry, but also the Aids Memorial Quilt and the headscarves of Argentina’s Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, embroidered with the names of their abducted children. They share a common language with shell-shocked World War One soldiers who learned to sew in hospitals, and Hmong women who invented their “story cloths” in refugee camps to preserve memories of home.

“Through time, communities denied a voice have turned to sewing to document and preserve their stories,” Hunter tells BBC Culture. “Nineteenth century schoolgirls in America charting their place in an emerging New World, Scots in the Great Tapestry of Scotland tracing their distinctive history and culture. Community embroidery is imbued with a collective spirit. This is a rarity in the world of public art, and such communal textiles offer a democratic medium through which shared values, celebrations and concerns can be distilled.”

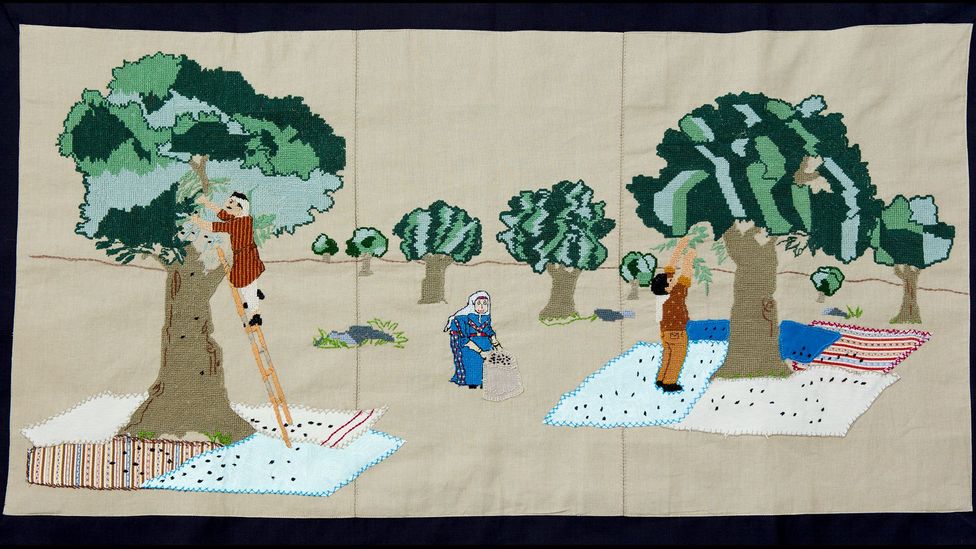

Needlework is a tradition that is often passed down through generations, so it can have a particular pull for people who feel far from home. The Palestinian History Tapestry is an ongoing charity project that traces the region’s history from the Neolithic era to the present day, and it employs Palestinian women within and outside the Palestinian territories to sew individual panels. Described to BBC Culture as “both a project of cultural activism and humanitarian aid” by Israeli historian Professor Ilan Pappé, it captures checkpoints and gunboats, but also countryside weddings, musicians, and the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish. Other panels echo BBC News images while Boys on the Beach recreates an image made by Israeli artist Amir Schiby in tribute to four boys killed in Gaza.

Dr Shayma Alwaheidi worked as the project coordinator for the Gaza branch of the Palestinian History Tapestry and tells BBC Culture that panels titled Olive Harvest and Henna Party bring back happy memories. “I myself am a refugee from Beersheba, my parents’ homeland, and the embroidery of The Key for Return means so much to me and to my family because it is our symbol of resistance, and the hope that one day we will be able to return.”

Palestinian history tapestry patron Professor Avi Shlaim (Emeritus professor of international relations at the University of Oxford) is well acquainted with the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the United Nations Resolution 194 of 1948, but he tells BBC Culture “it was a completely different experience” to see them stitched out. “I knew about this resolution from the history books, but it was much more vivid and emotional to see it on a piece of embroidery, symbolising something which is so fundamental to all Palestinians, which is the right of return,” says the British-Israeli historian.

The tapestry’s founder, Jan Chalmers, was inspired to start another Bayeux-inspired tapestry after teaching embroidery in the early days of the Keiskamma Art Project. Unlike the Bayeux, “the panels are as individual as the people who designed them and stitched them,” says Chalmers. It’s a choice that honours the history of Palestinian embroidery, “tatreez”, a practice that was added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list in 2021.

Palestinian researcher and educator Wafa Ghnaim is the author of Tatreez & Tea: Embroidery and Storytelling in the Palestinian Diaspora, and tells BBC Culture that tatreez is a fitting medium for such a project because in Palestinian history “each village, town, city and nomadic community carried distinct styles in their dress, from the colour palette used, to the symbolism of motifs”. After 1948, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled or were displaced from their homes, “the Palestinian dress evolved into a symbol of unity,” she says, and “the creation of the traditional dress became a reclamation process” to resist the narrative that they were “a people without land and a land without people”.

Ghnaim adds that during the First Intifada (1987-1993), images of Palestinian culture – including flags – were confiscated by the Israeli army. “Palestinian women began to embroider Palestinian flags, the Dome of the Rock, rock throwers and other symbols of resistance on to their dresses to wear to protests.”

“This slow process of creation speaks to the perseverance (sumud) and patience (saber) required of Palestinians to continue to fight for their freedom. These values continue to guide not only our resistance movement, but the skills required to endure the art of Palestinian embroidery.”

Across the world we can find community embroidery projects that answer a question posed by Lelethu “PoeticSoul” Mahambehlala when she showcased the Keiskamma Tapestry on the aBantu Podshack: “If we truly have power – should we not be rewriting the book, retelling the story, rearranging the songs, and adding new colour to the pictures? Is it not time we reimagined history?”

For Keiskamma artist Nozeti Makhubalo, the Keiskamma retrospective is also about looking at what lies ahead. “My future dream is to see the youth join the project. I need to see more young people as artists taking the art project to the stars.”

Umaf’ evuka, nje ngenyanga / Dying and Rising as the Moon Does Is at Constitution Hill, Johannesburg until 24 March, keiskammaartproject.org

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.