The original master of anti-minimalism

Why we still love original anti-minimalist William Morris

(Image credit: Queens Square collection from Morris & Co)

The 19th-Century maximalist and activist is still inspiring the artists and interior designers of today. Cath Pound explores why his vibrant, nature-filled designs speak to us.

W

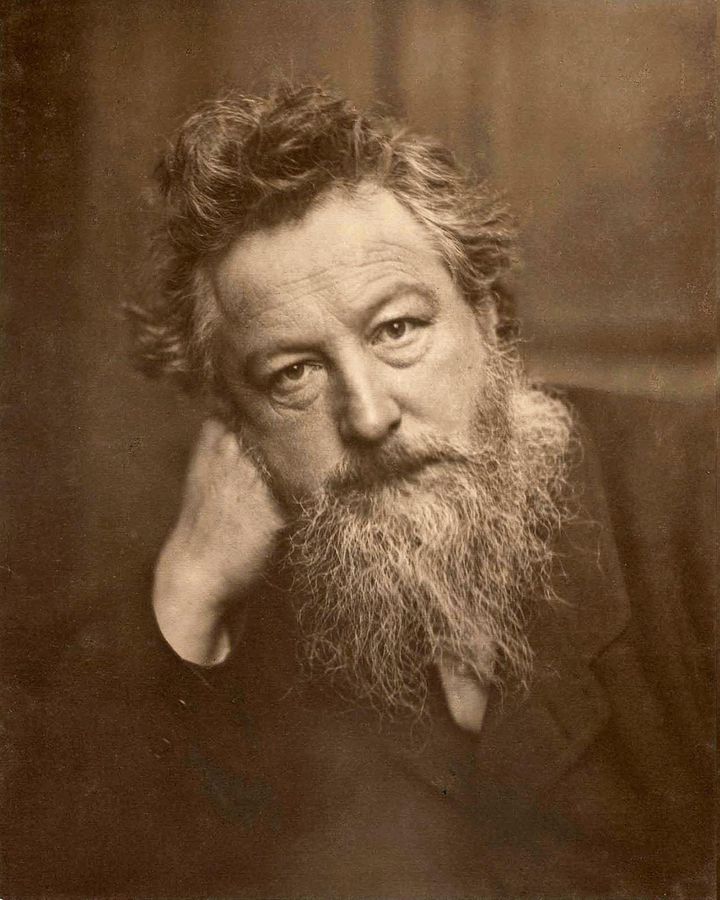

William Morris was undoubtedly one of the most original and radical creative forces of the 19th Century. With 2021 marking 125 years since his death, his designs are as popular as ever, helped by the occasional contemporary makeover, while his legendary versatility and activism continue to inspire new generations of artists and designers. His life and work is celebrated in a sumptuous new volume by Thames and Hudson, while his enduring influence is evidenced by the Victoria and Albert Museum’s acquisition of Portrait of Melissa Thompson by Kehinde Wiley, a US artist who has long been inspired by Morris’s designs.

More like this:

– The first eco-warrior of design

– The anti-minimalist trend for clutter

– Why Hogarth is the UK’s greatest artist

Although the original Morris & Co folded in the 1930s, the Sanderson group acquired the archive, and has continued to print the designs ever since. Seeking to explain their continuing popularity, Claire Vallis, creative director of the Sanderson Design Group, cites a number of reasons. “There’s the nostalgia of them – people remember them from their childhoods – and then there’s such storytelling in his designs that I think people really connect with them. A design like Strawberry Thief was inspired by Morris looking out of his window and seeing thrushes picking the strawberries which he found very amusing and created a story around.” The Morris aesthetic – with its vibrant patterns, full of intricate detail – is also a perfect fit for the current love of maximalism, eclecticism and nostalgia in interior design, a look referred by some on social media as “cluttercore“.

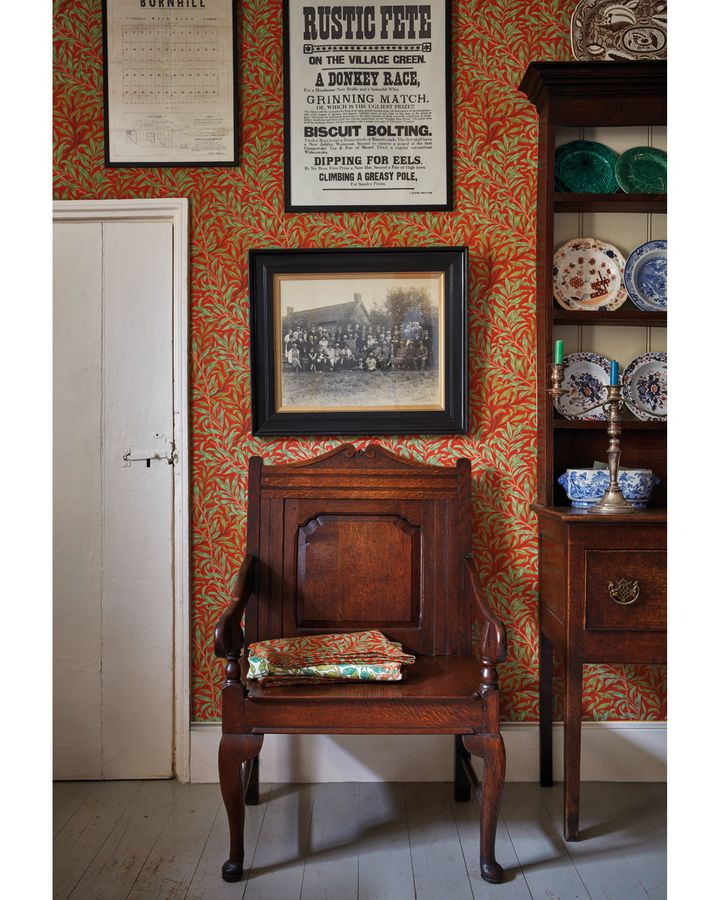

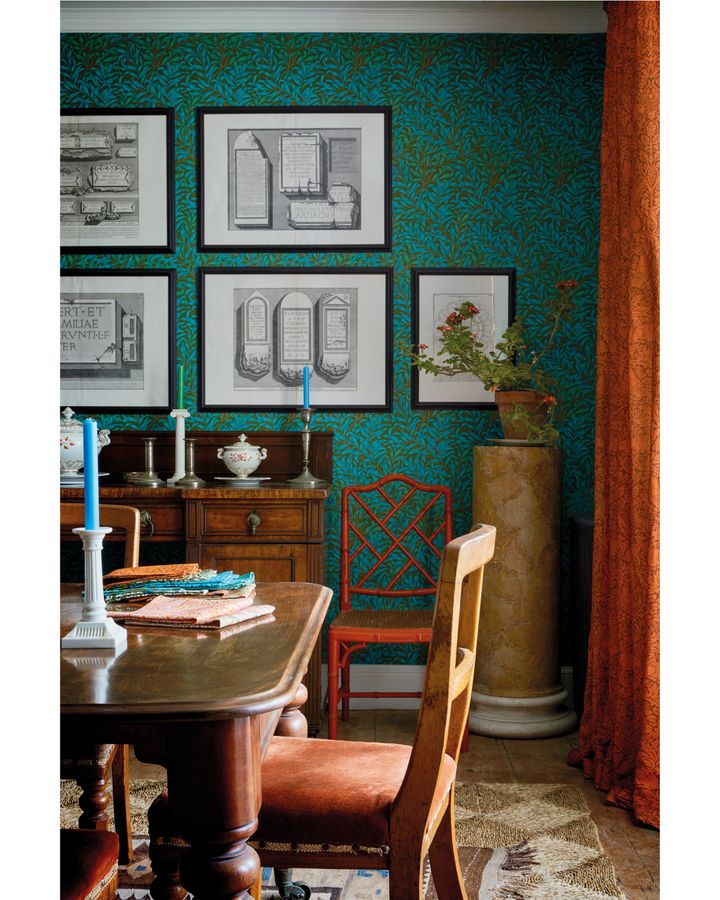

Morris’s designs have a romanticism and nostalgia about them (Credit: Queens Square collection from Morris & Co)

Strawberry Thief, along with the fecund florals of Lodden, are two favourite designs at London’s Liberty, a store which has long been associated with Morris. “There are certainly moments when interests in the designs peak but there is always a love and affinity to Morris for the Liberty customer,” Mary-Ann Dunkley, design director of Liberty fabrics and products, tells BBC Culture. Although the original designs and colourways are perennially popular, both Morris & Co and Liberty have experimented with different colour combinations. “We often recolour the designs and play with scale depending on the seasons and the trends. When a heritage Morris pattern is recoloured in a tonal way, they have a contemporary appeal and work really well with solid fields of colour – for example when used with plain fabrics and painted walls,” explains Dunkley.

Morris and Co’s Pure Morris range “explored the architecture of the designs, really paring them back,” says Vallis. “We used a lovely linen ground and then took an embroidered stitch effect to create the outline of his design. They’re incredibly popular in Japan and Scandinavia because they have this simplicity to them.”

At the other end of the spectrum are the vibrant colourways created by interior designer Ben Pentreath. “He’s always loved Morris and he’s used him in nearly all of his schemes, but when he came to the archive, he couldn’t believe that we still have the 1970s pattern books with all the colourways that he remembered from his childhood. Straight away he wanted to recreate those,” says Vallis. Iconic designs such as Willow Bows and Marigold have been recast in bold shades of red, turquoise and green, with Pentreath combining textiles and wallpapers to stunning effect. “He is very good at creating a variety of patterns and they all work very well together,” says Vallis. Pentreath’s enthusiasm, combined with the vast range of source material available to draw on in the archive, means another collection is planned for next spring.

Interior designer Ben Pentreath recast classic Morris prints in bold new shades for the Queen Square collection (Queens Square collection from Morris & Co)

Vallis says there has been a real return to pattern recently, and that the ageless appeal of Morris’s designs undoubtedly adds to their attraction to consumers who might want to experiment. “Morris has that reassurance, you know if you dip into pattern it will have longevity, it’s not going to go out of fashion.” Their versatility is also a factor. “They cross over so well from a contemporary to traditional interior and from city to country,” says Dunkley.

This is certainly part of their attraction for interior designer Rachel Chudley. “I like to use Morris designs in unlikely areas to give them a new perspective and lease on life. There is a great joy in sitting great design from very different eras next to each other and seeing what they do to each other,” she tells BBC Culture via email. For one of her projects, she says: “I chose a deep, rich Morris forest scene to create the feeling of a secret garden in a lower ground floor kitchen”.

Chudley believes that Morris’s respect for nature and his opposition to industrialisation also plays into his appeal. “We are seeing a huge love for craft and a handmade, carefully designed quality with our clients. I think a big part of this is a reaction to the digital surface world. Just as the Romantics retreated from overpowering industrialisation, people now are attracted to the sensory real-life experiences that seem to be choked out by social media.”

The artist’s way

The diversity of Morris’s oeuvre also means there are multiple strands for contemporary artists to draw on, from the purely aesthetic to the social and political. Kehinde Wiley has been using Morris’s designs as a backdrop to his portraits for more than 15 years. His Yellow Wallpaper series, of which the V&A’s acquisition is a part, was inspired by Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1892 feminist text of the same name, which highlighted the consequences of denying women independence via the story of a woman confined to her bedroom following a diagnosis of hysteria. Wiley has said he wanted “to use the language of the decorative to reconcile blackness, gender, and a beautiful and terrible past”. Although Wiley’s interest in Morris was initially purely aesthetic, he also discovered an unexpected historical link via The William Morris Gallery, where the series was first exhibited in 2020: Perkins Gilman “knew Morris and she corresponded with his daughter May,” explains curator Rowan Bain.

US artist Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Melissa Thompson (2020) interprets a Morris design (Credit: Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery/ Todd-White Art Photography)

The William Morris Gallery frequently holds exhibitions of artists inspired by Morris, and also runs an artist-in-residence scheme. “It’s not asking people to create something that looks like Morris might have made. He’s so rich in his thinking and his ideas, it’s very much to see how contemporary artists can use him as a catalyst to explore something further,” explains Bain. The gallery is particularly enthusiastic if a project brings in new audiences. Studio Carrom, which consists of print designer Nia Thandapani and illustrator Priya Sundram, chose to explore Morris’s connections with South Asia.

“Often it’s a footnote or an aside that Morris was influenced by South Asian patterns and cottons,” explains Bain. The duo used their residency and a later exhibition as an opportunity to work with the South Asian community who live around the gallery, and bring them into a space they rarely visited. “Morris was a white wealthy man living in the 19th Century and we can’t take him out of that context, so it’s really important to us that people who come to the gallery can see themselves though contemporary responses,” says Bain.

The gallery is always looking to explore Morris in new and unexpected ways. “Something we’re really interested in and haven’t yet found is someone to look at digital processes. There’s a lot of potential for exploring digital pattern-making or Morris’s work in a digital way,” says Bain. Perhaps the lack of candidates is down to misconceptions about Morris and technology. “It’s not totally true to say that he was against all machine processes. He was interested in it when it could benefit quality and benefit the maker. For example, for his tapestries, he had photographs of his designs taken and then blown up very large so his workers could work from the prints,” says Bain. “It would be interesting to think what he would be like now. Would he be like David Hockney and embracing the iPad?” she muses.

A love of nature was integral to Morris’s aesthetic – and also to his world view (Credit: Alamy)

“He’d run an ethical tech company and probably a political party at the same time,” says Turner prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller when asked to consider what Morris might be doing if he were alive today. “He was into technology, into process, into design. He did more or less everything that an artist could do. It proliferates your interest in them because their careers are so sprawling, what we’d call multimedia. You can take what you want from people like him because his career is so huge, it’s such rich and fertile ground”.

Deller has used Morris’s work in numerous ways. In 2014 he curated a show comparing his and Andy Warhol’s careers. Although the two artists are seemingly worlds apart, Deller sees them both as “artists of their time and artists of the future at the same time… they were both world-changing artists whose influence just gets bigger,” he says.

He also memorably created a mural of Morris hurling Roman Abramovich’s yacht into the Venice lagoon. “That was him as an activist giant, a colossus of history, in terms of his ideas but also his abilities and activism,” says Deller. “He loved Venice so he would have hated the way it has been despoiled by these yachts, even though he might have been interested in the design of them.”

UK artist Jeremy Deller’s 2014 mural depicts William Morris as ‘an activist giant, a colossus of history’, hurling a superyacht into the Venice lagoon (Credit: Alamy)

“His political beliefs are very relevant right now, his love of nature and his disgust at how it [was] being abused and how elites [were] destroying lives. His relevance is much more than any other Victorian visual artist,” says Deller.

Morris’s influence shows no signs of diminishing 125 years after his death, and on a purely aesthetic level there is still more to discover. “We’re always trying to pull out a new design, there are still designs in the archive we haven’t explored, so we keep on bringing new things to market,” says Vallis. Deller’s colossus of history seems likely to straddle the 21st Century too.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.