The music most embedded in our psyches?

When we’re playing a videogame, we’re also dancing to its tune: catchy or haunting melodies; audio clues that spur us to quicken our pace; triumphant notes to confirm our success. When we hear this music outside gameplay, it can prove unusually moving. The first time I caught the London Video Game Orchestra in concert, I found myself hollering for my favourite characters during the Street Fighter II medley (Yoko Shimomura’s exhilarating 1990s soundtrack, specially arranged here by Mark Choi). I also joined a surreal singalong, as LVGO conductor James Keirle swept the audience into a classic console start-up theme: “Se-ga!” It felt like a five-second hymn: nostalgic and weirdly rapturous.

More like this:

– The forgotten pioneers of electronic music

– How the first pop star blazed a trail

– An album that defined the 20th Century

“SFII was honestly one of the most enjoyable arrangements I’ve done,” enthuses classically trained musician, composer and life-long gamer Choi. “The individual themes are pretty short but intensely memorable, and irrevocably intertwined with their characters and the stages on which they fight. When themes get so deeply embedded into our psyche like this, it’s impossible not to be moved when hearing them again.”

Choi adds that while there are many parallels between videogame and movie soundtracks (such as title sequences, recurring character motifs, and narrative cut-scenes), gaming’s non-linear, participatory nature means that the music strikes a potent chord in us: “The power of videogames lies in the fact that you actually become the protagonist of the story; although the story itself may have been predefined, you control how and when it unfolds,” he says. “It’s precisely this power – that you’ve been given to interact directly with the experience – that makes videogames stand apart and continues to excite me as an artist.”

The upcoming Prom is the latest in a line of concerts that includes Video Games Live, a tour with different orchestras (Credit: Getty Images)

Videogame music really does play our emotions. Its impact and increasing sophistication has inspired a growing number of academic studies (in a field sometimes tagged “ludomusicology”); in their 2006 essay The Role of Music in Videogames, Sean M Zehnder and Scott D Lipscomb noted the multi-functionality of gaming soundtracks; they “enhance a sense of immersion, cue narrative or plot changes, act as an emotional signifier, enhance the sense of aesthetic continuity, and cultivate the thematic unity of a video game.”

Ontario-based academic and filmmaker Karen Collins is associate professor at the University of Waterloo, and her excellent book Game Sound (2008) explores the history, theory and practice of videogame music and sound design. As Collins observes, the gamer is not a passive listener, but can actively trigger music in the game, as well as subconsciously reacting to it; she writes that “Mood induction and physiological responses are typically experienced most obviously when the player’s character is at significant risk of peril, as in the chaotic and fast boss music… sound works to control or manipulate the player’s emotions, guiding responses to the game.” She points out that silence is additionally used to powerful effect, whether heightening tension, or when the player is inactive (a musical fade that she describes as the “boredom switch”), prompting us to finish the task so that the game can progress.

Videogame music is a global expression, both in its international studio collaborations and audience reach. Earlier this year, the Poland-based Game Music Festival presented a London concert, including a Polish big band performing the boisterously jazzy, Latin-inspired grooves of much-loved adventure Cuphead (2017), composed by Canadian artist Kristoffer Madigan. The concert finale focused on LA-based Brit composer Gareth Coker’s enchanting (and devastatingly beautiful) award-winning scores for the games Ori and the Blind Forest (2015) and Ori and the Will of the Wisps (2020).

Coker originally studied composition at the Royal Academy of Music, and later lived in Japan; his musical range is expansive, including scores for film and TV – but his love of videogames runs especially deep. “Growing up, I have the fondest memories of playing videogames with my parents,” he explains. “Those memories I’ve created with my own family, I’d like to be able to give to someone else.”

For the Ori games, Coker spent several years with the development team, creating music that feels distinctly attuned to the title character/player role (a child-like forest spirit), and supernatural surrounds. “I respond heavily to visuals when I’m working on a game; then I can really get inside creating a soundworld for them,” he says. “The visuals in Ori allow me to create that tapestry with the music, because we’re asking people to expand their imaginations.

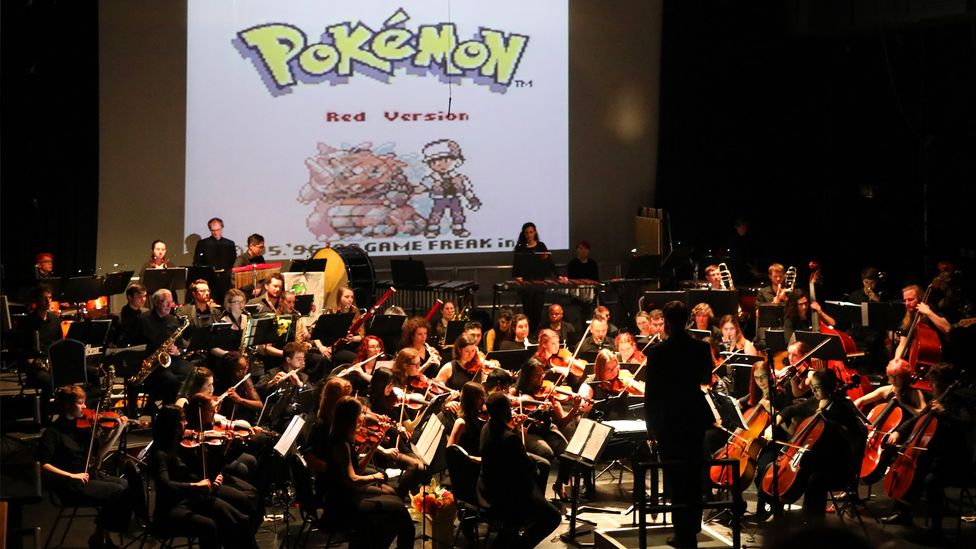

The LVGO’s repertoire includes pieces from Pokemon, Halo, Final Fantasy, The Legend of Zelda and Assassin’s Creed 4 (Credit: Rancho Dass)

“When you’re playing a game, you’re an active participant, so your brain has to handle a lot more. So how you write game music is fundamentally different, and the best games understand that you can’t pile on everything, unless you’ve built up to that moment. When you’re moving through Ori’s environment, the music doesn’t change all the time, because that’s too much for the brain to deal with. Every musical cue is placed for a reason. There is a melody in Ori, but it’s quite withdrawn and gentle, until it absolutely needs to take over.”

This sensitive touch can yield a mighty emotional punch, as anybody who has encountered the Ori games and music can attest; they’ve also inspired numerous online “reaction videos” (with gamers invariably in tears by the ending). “I’m insanely lucky, because now we have sites like Twitch and YouTube, I get to see other people reacting to my work, in the way I remember reacting myself,” smiles Coker. “It’s kind of addictive; you get a real-time visceral reaction.”

Spectrum of emotions

Coker’s varied soundtracks seem to summon a spectrum of emotions, whether it’s his music for the Minecraft Mythology series (“It’s like a jukebox, designed to transport the player to that time and place; it gives the brain room to build,” he says), or his contributions to the latest instalment of a role-playing blockbuster, Halo Infinite (2021).

“While Halo is an action score, it’s not wham-bam-in-your-face for hours on end; it’s very precise and measured, much like the main protagonist, Master Chief; nothing fazes him on the battlefield,” says Coker. “Combat music is designed to make you feel like you really are a very powerful soldier; Halo is very rhythmic and groove-based, which is designed to make you feel confident when you walk through the environment. In the final level of the game, I basically had carte blanche to do what I want. We ended up using a Bulgarian choir and a ton of synths, over-processing traditional folk music to make it sound really otherworldly; it created quite a distinct sound for a new faction, the Endless.”

Coker mentions that he’d like to see more classical concerts present long-form videogame symphonies, and engage gamers and non-gamers alike. “If you get it right, you’ll leave the audience with something much more profound,” he says. “We’re looking to transport people to a time and place, and you cannot do that if you’re clapping every five minutes, because the immersion spell is broken.”

Each hotly anticipated videogame brings its own soundworld; the recent samurai adventure Trek To Yomi blends monochrome visuals with a heavily atmospheric score by Cody Matthew Johnson and Yoko Honda. The imminent new Cuphead game, The Delicious Last Course, promises fresh bops from composer Kristoffer Madigan, who tells BBC Culture: “While it retains much of the exciting, uptempo big band stylings from the original Cuphead, we have explored many styles and sounds new to the Inkwell Isles… my biggest inspirations were the early film scores of Max Steiner and Erich Korngold, as well as Disney’s Leigh Harline and Frank Churchill.”

This summer, videogame music also makes it to the BBC Proms, for the first time ever. From 8-Bit to Infinity on 1 August presents orchestral and electronic themes, including Shimomura’s classic Kingdom Hearts and the European premiere of Hildur Guonadottir and Sam Slater’s Battlefield 2042 – suite 14. As conductor/arranger Robert Ames says: “Videogame music has been on the cutting edge since its inception. Those early consoles were very basic compared to the technology we have now, and composers were really pushing them to the limit. I think that spirit is still very much part of videogame composing now.”

Composer Gareth Coker has created award-winning scores for games including Ori and the Will of the Wisps (Credit: Moon Studios)

Meanwhile, the LVGO’s next London concert (11 June) rewinds Choi’s Street Fighter II medley, and adds a vocal level to the show, with community choir Ready Singer One. “We’re all nerds and gamers to some extent, so RS1 is a safe, empowering space to be creative and explore our favourite universes together,” says founder Elisabeth Swedlund. “Singing about so many diverse characters and challenges is, each time, an immersive experience. Because the themes are much more varied than in pop repertoire – we’re pirates, sailors, AI! – the experience of being in a choir is much richer.

Their set list includes the exuberantly jazzy Jump Up Super Star from Super Mario Odyssey (composed by Naoto Kubo, 2017). “The piece has a variety of ‘Easter Eggs’, both in the words and in the music,” says Swedlund. “There’s a moment where we sing an exclamative “woo-oh!”, and we very much feel like Super Mario bouncing around!” Videogame music offers an infinite playlist: transcendent and transformative, resonating way beyond game over.

The London Video Game Orchestra perform at Woolwich Works, London on 11 June.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.