The most subversive western ever made

As the idealistic 1960s gave way to the cynical 1970s, US cinema began serving up increasingly nihilistic and psychologically complex stories, all with sour endings to match. Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Easy Rider (1969) foretold the death of the hippie dream. But the western had it in its sights too. Released in 1969, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Desperados, and The Wild Bunch all ended in calamity and bloodshed, all their key players slain. Many more westerns of the era had similarly shocking, symbolic conclusions. Though ostensibly designed to convey the death of the Old West, these end-of-the-line westerns also echoed the way the flower-power fantasy wilted in the wake of the Tate-LaBianca murders, the violence at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival, and the escalating tensions of the Vietnam War.

More like this:

– The films tackling the toxic cowboy

– Why El Topo is the weirdest western ever made

– The legacy of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

But amid these hard-boiled westerns came a different, and softer, film. Released in 1971 and billed as “the first electric western”, Zachariah was chiefly a musical comedy. Ostensibly set in the late-1800s, it boasted an anachronistic, diegetic soundtrack from 1960s rock acts such as the James Gang, White Lightning and Joe McDonald, and plays out as part dusty Woodstock concert film, part acid western à la El Topo (1970), and part pre-Blazing Saddles (1974) genre parody. But it’s in the communion between its protagonists Zachariah and Matthew that the film’s most meaningful messages are found. Like Kelly Reichardt’s recent First Cow (2019), and Jane Campion’s Oscar-tipped The Power of the Dog (2021), Zachariah shot back at the genre’s fatalistic masculinity by celebrating peace, pacifism and, most remarkably, intimate male friendship.

Zachariah was dreamt up by writer-director Joe Massot, whose debut feature Wonderwall (1968) had been scored by George Harrison. Following its release, Massot found himself in India, engaged in transcendental meditation alongside the Beatles. There, while Harrison and John Lennon were locked in a meditative stand-off to see who had the stronger resolve, Massot was struck by the idea of two friends duelling in the desert for spiritual supremacy. Massot based his screenplay on Hermann Hesse’s novel Siddhartha (1922), a tale of two friends and their divergent paths towards enlightenment. It was to be a deeply psychedelic movie, a western characterised more by its out-there visuals than by any moral message.

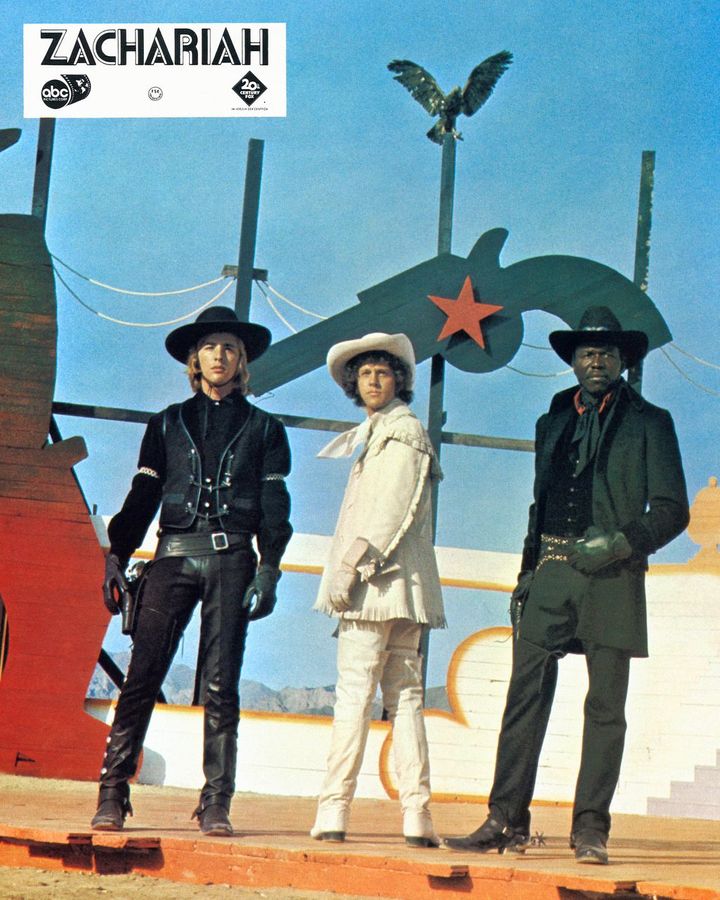

Released in 1971, Zachariah was part acid-western a la El Topo, part pre-Blazing Saddles genre parody (Credit: Alamy)

Massot was in talks with the Beatles’ Apple Films to produce the movie. Lennon would later be instrumental in catapulting El Topo to cult status by praising it publicly; perhaps he could do the same for Zachariah. Massot wanted Bob Dylan to play the eponymous character and The Band to play the Crackers, the film’s literal band of outlaws. Brigitte Bardot was earmarked for the role of sultry showgirl Belle Starr. Drummer Ginger Baker was attached to star too. None of them did. ABC Pictures eventually optioned it and hired surrealist four-man comedy troupe the Firesign Theatre to punch up the script. The US group’s satirical radio broadcasts and comedy albums – made by hippies, for hippies – would go on to be influential across the audio-comedy spectrum. This was going to be their big break in Hollywood.

“Every boy wants to be in a western,” David Ossman, who formed Firesign with Peter Bergman, Phil Austin and Phil Proctor in 1966, tells BBC Culture over Zoom. “That’s the first thing you want to write. You want to get on that horse.” Firesign saddled up in June 1969. The troupe pared back Massot’s visual flourishes to make space for new gags and new dialogue. The director didn’t like dialogue, so he quit, leaving producer George Englund to take charge. “We were thrown into this tumultuous situation,” Phil Proctor tells BBC Culture, “with a director who was visually oriented and an extremely literate producer who was asking us to cross every t and dot every i. We wanted to dot every t and cross every i.”

Pictured in For a Few Dollars More, Clint Eastwood’s man-with-no-name archetype influenced scores of western anti-heroes (Credit: Getty Images)

Weaned on golden-age westerns such as High Noon (1952), Shane (1953) and Gunfight at the OK Corral (1957), Firesign were keenly aware of what a western should look and feel like: dusty desert roads, solitary strangers with shady pasts, pistols at dawn and the climactic duel between good and bad. But the young group also wanted to subvert such expectations and promote the era’s anti-war movement by showcasing peace and pacifism and somehow diffusing that final shootout. Englund, a generation older, wasn’t hip to that. “Not only did he not understand it as a producer,” says Proctor, “he didn’t understand it as a director.”

The story begins as Zach (played by newcomer John Rubinstein) receives a mail-order gun in the middle of the desert, after which he and Matthew, played by a gorgeous Don Johnson, decide to become outlaws proper. When the boys head off to learn from fearsome gunslinger Job Cain (Elvin Jones), both looking to become the fastest draw in the West, Cain pits the pair in friendly competition. But Zach, foreseeing a future in which one of the boys must kill the other, won’t play. He departs, while Matthew, seduced by the outlaw lifestyle, refuses, which leads Zach to utter three little words all too rare to the genre – and especially between men. “I love you, Matthew,” he says. “We said we’d stay together.”

Men with no name

Historically, western protagonists have not been forthcoming with their feelings. John Wayne and Gary Cooper’s characters were “men’s men”, celebrated for their stiff upper lips, broad shoulders and steely resolve. Even when they saved the West and got the girl, the resulting relationships were hardly teary-eyed love-ins. But by the time of Zachariah’s release, US westerns had long been taking cues from their European derivatives and even paper-thin relationships like these were less prevalent. Clint Eastwood’s man-with-no-name archetype established in Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy proved hugely popular. Invulnerable, detached and ethically compromised, Eastwood’s profile in these films would influence scores of western anti-heroes similarly written to embody the corruption endemic to the Old West. Admissions of even heterosexual love were infrequent from these figures. Not only were Zachariah’s protagonists younger and prettier than the grizzled veterans of these gritty westerns, they were also more emotionally available.

Once the boys split up, Zach finds and rejects another kind of love elsewhere. In the town of Camino, he sleeps with showgirl Belle Starr before retreating to an isolated farm, where he cohabits with an elderly man. In westerns, the wilderness – rugged, dangerous, untamed – is a place for men, while the homestead is typically a feminine sphere, kept and commanded by women. Zach adopting a life of domesticity again disrupts the genre’s masculine ideals, the notion that “real” men can exist only in the wastelands, unable to be at peace in the civilised spaces they have sworn to protect. Matthew is becoming one such man. Having overcome his mentor Job Cain in his quest to be the best, there’s only one gunslinger that Matthew has yet to beat: Zach. The film’s climactic duel is set: opposing philosophies settled with a single gunshot. But were it not for Firesign’s subversive streak, its conclusion would’ve been very different.

Zachariah’s screenplay was rewritten many times. But the most crucial alteration that Firesign made to Massot’s original script remained: the ending. By the early 1970s, gruesome movies such as The Wild Bunch, Soldier Blue (1970) and Ulzana’s Raid (1972) had earned the title “Vietnam westerns” for comparing the savagery that the US was meting out overseas with its mythic history of “taming” “savage” lands. But Firesign’s history with the genre was more innocent.

“We were coming out of that line of beautiful 1950s westerns,” Ossman tells BBC Culture. “In the cowboy movies we watched as kids, it’s ‘bang, you’re dead’. What Peckinpah did [with The Wild Bunch] was violate your expectations. Instead of ‘bang, you’re dead’, it’s ‘bang, you’re all over the screen’.”

Massot’s original script ended with Zach gunning Matthew down, hero besting villain. It was important to Firesign to undercut that, while undermining the escalating severity of the genre and addressing the Vietnam War. When Matthew arrives on the farm, he’s disturbed by Zach’s new life, threatened by the idea of settling down in a distinctly feminine habitat. He instigates a duel but Zach slips away, which causes Matthew to break down and cry. “I can’t do it alone,” he says. Matthew needs Zach, and his cries turn to laughter as he realises that Zach’s love for him outweighs his capacity for violence. And so, Matthew flings his gun away and goes to Zach and, still on their horses, still cowboys, the two embrace. In riding out to Zach, Matthew reciprocates the love that Zach extended him earlier. “What Peckinpah was trying to say was, ‘This is what’s happening in Vietnam’,” says Ossman. “Whereas what we were saying was that it doesn’t have to be that way.”

Firesign’s most crucial alteration to the film was its ending, which became a celebration of pacificism and love (Credit: Alamy)

Pacifism is key to Zachariah. It didn’t have to be that way, even if key figures of the western genre thought otherwise. Consider John Wayne and Howard Hawks’ infamous reactions to High Noon, in which Gary Cooper’s town marshal tries and fails to recruit townsfolk to help him defend Hadleyville from an incoming threat, before overcoming the threat himself and then throwing his marshal’s badge to the ground in disgust. Wayne told Playboy magazine in 1971 that High Noon was “the most un-American thing [he’d] ever seen in [his] whole life”. Hawks said that he “didn’t think a good sheriff was going to go running around town like a chicken with his head off asking for help”. The message was clear: asking for help is a sign of weakness. In response to High Noon’s “lily-livered”, “un-American” undercurrents, Wayne and Hawks made Rio Bravo (1959).

Zachariah is clear in its celebration of pacifism: over the course of the film, Zach flees from multiple fights yet is never branded a coward. Gary Needham, senior lecturer in film at the University of Liverpool, calls it “the whole make-love-not-war ethos” that was embedded in the era’s counterculture. In all its Firesign-fuelled youth-culture provocation, Needham tells BBC Culture, the film “captures the overlap between anti-Vietnam War, rock music, sexual liberation, feminism, the emergence of gay rights, civil rights, environmentalism – they’re all coalescing”.

The boys’ embrace at the end of Zachariah, then, is an earnest rebuttal of the toxic, violent masculine mores on which the western genre was built. But it wasn’t written that way. “We were part of the youth movement, the anti-war movement,” says Proctor. “We were making fun of the movement in order to open people’s minds to it. Part of the message was ‘love and peace, maaan’. George didn’t understand that it was kind of tongue-in-cheek. If you put it in the context of a shootout in a western, and the ending is, ‘Come on, let’s not do this, I love you, man’, that’s a joke! But that was not understood.”

Queer cowboys?

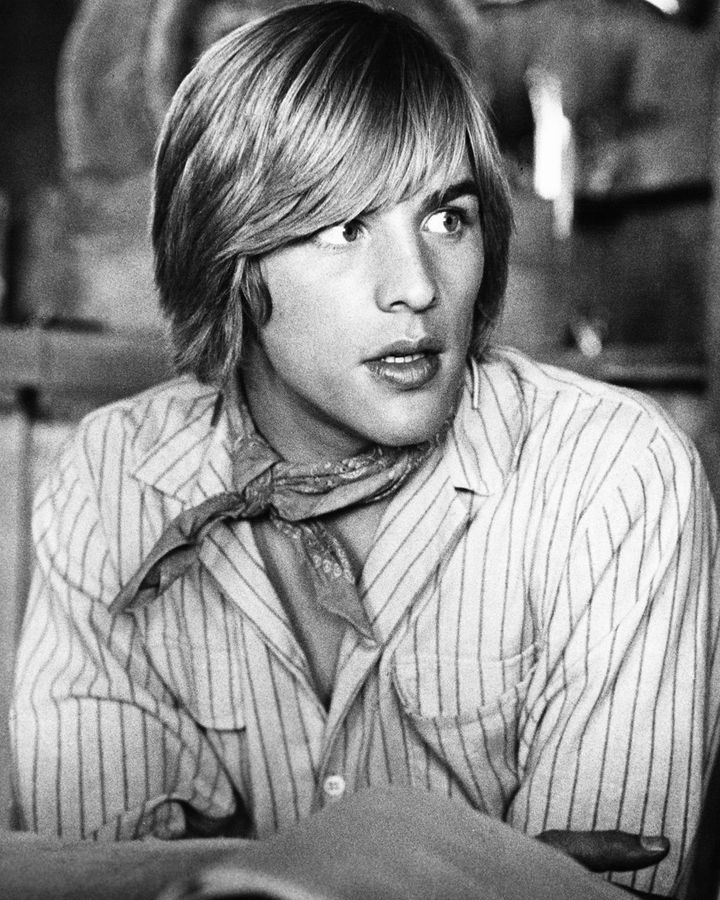

So is Zachariah a gay western? The gay press asked the same question. With Don Johnson gracing its cover, the March 1971 edition of The Advocate, the US’s oldest LGBT publication, featured a review with the headline “Are they gay?”. Harold Fairbanks, The Advocate’s film critic, wasn’t convinced. On the homosexual implications of the friendship, he wrote, “I’m afraid that’s all it is – friendship,” adding that the film’s script leads to the brink of homosexuality only to back away before it becomes explicit.” Gay people will be positive that the boys were lovers, and the straights will be left with only suspicions.” Other publications, including Variety and the Independent Film Journal, neglected to address the film’s queer undercurrents at all. The New York Times’ Roger Greenspun looked closer (too close, perhaps), concluding that the film “propagandised homosexual love“.

Still, the signs are there. In his book Idol Worship: A Shameless Celebration of Male Beauty in the Movies (2003), Michael Ferguson refers to Johnson at this stage of his career as “an instant hit with gay audiences”, and “sold as chicken feed and pecked at with delight”. Johnson’s first feature film was The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart (1970), a hippie-exploitation film in which the then-21-year-old masturbated and appeared naked. Nude stills from his works were regularly printed in gay magazines, and Johnson was, says Ferguson, “extremely gay-friendly and gay-thankful”. The actor’s sexual appeal would continue into Zachariah. When Zach first approaches Matthew, he’s shirtless and sweaty, wearing little but a blacksmith’s smock, Ferguson wrote: “the homoerotic possibilities of this exchange [might] turn it into the first gay western since Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys (1969)”.

Not long after the boys’ first scene together, they are accosted by a man at a local saloon. “You and your girlfriend looking for trouble, huh?” he says to Zach, before calling him “Annie Oakley”. Slurs such as these were often thrown at hippies and long-hairs, and the exchange is meant by Firesign to signify the misadventures of the counterculture youth. But the sequence speaks to the experiences of many gay men too. Zach, for his part, remains unperturbed when his sexuality is called into question. Matthew, meanwhile, glances at his partner’s crotch when the aggressor says, “Look what the tough little boy has in his pants”. The film, however, is sapped of this frisson whenever Johnson is off screen. “Like all love stories,” says Ferguson, “it desperately needs the boy/boy sexual tension.”

As Matthew, Don Johnson first appears shirtless and sweaty, wearing little but a blacksmith’s smock (Credit: Alamy)

But the boys love each other, right? That may be. However, like Fairbanks of The Advocate, Needham isn’t convinced that their love is anything other than platonic. “I think it’s a gesture of intimacy rather than romantic love,” he says of the exchange between Zach and Matthew, “but it’s still super-radical to see men say that to one another in a genre that otherwise has been very clear-cut about its ‘manly’ men.”

Masculinity is not innate to anyone, not least the western protagonist. Instead it is a learnt practice and, until about the 1970s, the western was a predominant mode through which masculine performance was taught, especially to young white American men. “From roughly 1900 to 1975,” writes Jane Tompkins in her 1992 book West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns, “a significant portion of the adolescent male population spent every Saturday afternoon at the movies” watching westerns, which, she adds, “carry within them compacted worlds of meaning and value, codes of conduct, standards of judgement, and habits of perception that shape our sense of the world and govern our behaviour.”

Still, despite the genre showcasing a mostly clear-cut picture of manly US masculinity, that doesn’t mean it hadn’t raised eyebrows before. Red River (1948), a film laced with innuendo in which John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, a closeted gay man, admire each other’s firearms, was labelled a queer touchstone – alongside Calamity Jane (1953) and Johnny Guitar (1954), which also upended gender roles – in Vito Russo’s 1981 book The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, and the documentary of the same name (1995). During the 1960s and 1970s, the queer themes explored in these westerns would become more explicit as the film industry began to interrogate the myths upon which one of its oldest genres is built. Andy Warhol’s Horse (1965) and Lonesome Cowboys (1969) make clear the connections between costume, American male identity and homosexuality. “The cowboy has always had a lot of currency in gay erotica and eventual pornography,” says Needham, who points also to gay-liberation films such as Song of the Loon (1970), and gay porn features such as The Savages (1971), as examples.

In 1969, Midnight Cowboy would repackage these themes and aesthetics to ask questions about America’s models of masculinity. Needham writes in his essay Hollywood Trade: Midnight Cowboy and Underground Cinema, the film “‘outs’ post-war gay culture’s cultural production and erotic fascination with cowboys”. Zachariah isn’t as explicit with its themes as Midnight Cowboy but the films share a clear interest in man-to-man intimacy rather than mano-a-mano showdowns: like Buck and Rizzo, Zach and Matthew care deeply about one another, even if only platonically. That, says Needham, might be part of Zachariah’s appeal to gay audiences: because it depicts men, even if they’re not interpreted as gay, as unbound by the masculine paranoia that surrounds touch, feelings and emotions. “For some men,” he says, “any type of male-male intimacy is to be feared.”

There was clearly a precedent for gay cowboys by 1971, even if it was mostly unknown to Zachariah’s makers. But whether Zach and Matthew ride into the sunset as friends or lovers is irrelevant. Ironic or not, the film is a celebration of the intimacy with which the US archetype of the cowboy has traditionally been afraid or unwilling to engage. And as Sam Elliott’s controversial comments regarding Jane Campion’s The Power of The Dog’s “allusions to homosexuality” this week show, it’s an archetype that some find hard to shake.

Whether by accident or design, Zachariah did things differently. Through their love, the boys not only sidestep the toxic masculinity and nihilistic isolation that ensnared so many golden-era western protagonists, who choose to trot off into the wilds rather than be accepted into civilisation’s outstretched arms, but also the bloody fate that befell the Vietnam-era gunslingers too.

“We gotta start thinking beyond our guns,” says Pike Bunch, the leader of the Wild Bunch. Zach and Matthew already had. Where Peckinpah’s Bunch choose to go out the only way they know how, in a hail of bullets, Zach and Matthew choose not to go out at all. Together, they undermine the western, the war and the western’s response to it. Their spiritual enlightenment comes as they throw down their weapons, both having found what they’re looking for.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.