The Lord of the Rings’ ancient roots

Despite being set thousands of years before the novel itself, Amazon Studios’ new prequel to The Lord of the Rings promises to contain many of the ingredients beloved by Tolkien fans. Its characters include Galadriel and Elrond (both elves, who are conveniently immortal in Middle-earth) and small folk known as Harfoots that turn out to be the Hobbits’ evolutionary predecessors – and then there are the iconic symbols that provide the series with its title: The Rings of Power.

More like this:

– Why the world’s most difficult novel is so rewarding

– Did Tolkien write ‘juvenile trash’?

– Hobbits and hippies: Tolkien and the counterculture

The series takes its cue from an appendix Tolkien wrote for the final instalment of his epic, slenderly outlining the history of Middle-earth’s Second Age. This was a time when the legendary rings were forged and the dark Lord Sauron rose to power, a time when the island kingdom of Númenor flourished (and then fell), and elves and men were compelled to band together in order to do battle for the soul of Middle-earth. By necessity – legal as well as creative (Amazon doesn’t own the rights to posthumously published materials in which Tolkien goes into greater depth on the Second Age) – the show’s writers have had to alter and embellish, compressing time frames, inventing new characters and tinkering with the storylines of some canonical creations.

As the series gets underway, there’s sure to be plenty of debate over how faithful it is to Tolkien’s vision, but just how original that vision was in the first place is a subject that’s long enthralled scholars. One thing is certain: even as it harnesses all the cinematic razzle-dazzle that its mega-budget can buy (it’s reportedly the most expensive television series ever made), in channelling the imagination of an Oxford don writing in the middle of the last century, the series will also be tapping into lore and legend from literature too ancient to be accurately dated, whose narratives are full of heroism and tragedy, dwarves and elves – and of course magical rings.

Amazon’s new series The Rings of Power is a prequel set thousands of years before the events in Tolkien’s novel (Credit: Amazon Studios)

It’s sometimes assumed that Tolkien was inspired by the most famous ring in opera, Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungs. The German composer began work on the libretto and music for his cycle almost a century before Tolkien first introduced his rings to readers with the publication of The Hobbit in 1937. Tolkien himself was dismissive of the notion, famously writing to his publisher: “Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceases.” Yet as his biographer John Garth tells BBC Culture, “It’s a moot point, because there are other resemblances – power, a corrupting influence.”

It’s still more understandable that by the time The Fellowship of the Ring, the first instalment of the trilogy that’s now published as The Lord of the Rings, appeared in 1954, Tolkien would have wanted to distance himself from a composer who had become deeply problematic. In a letter written during World War Two, the author can be found railing against “that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hilter” for “ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble Northern spirit”. That the Nazi leader felt such an affinity for Wagner would have been more than enough to turn Tolkien fully against his Ring Cycle.

What’s generally agreed is that both Tolkien and Wagner drew inspiration from the same sources, chiefly Nordic sagas. In the UK, after 19th-Century academics and archaeologists rehabilitated the Vikings, the public appetite for all things Norse had become huge. It was even claimed that Queen Victoria was descended from the god Odin, and that the entire Hanoverian royal family was related to Ragnar Lodbrok, aka Ragnar Hairy-Breeches. For Tolkien, born in 1892, the obsession began in childhood, when he read Andrew Lang’s Red Fairy Book and fell in love with the story of Sigurd the dragon-slayer.

“As a teenager at King Edward’s school in Birmingham, Tolkien began reading Norse sagas in the original medieval Icelandic (West Norse) and even presented a paper on the subject to the school’s Literary Society in 1911,” Grace Khuri, an Oxford University doctoral researcher, tells BBC Culture. Her thesis, which covers the influence of Norse mythology on the writer, is the first Tolkien-related thesis the author’s alma mater has deemed rigorous enough to allow. “He also treated his closest friends to informal, spirited recitations of Old Norse and other medieval material,” she adds.

At Oxford, Tolkien initially studied Classics but his interest in predominantly Germanic languages led him to switch to English, a course steeped in Old and Middle English literature and philology. Though already a devout Roman Catholic, he became enthralled by texts that seemed steeped in remnants of pre-Christian belief, among them Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, whose pages are haunted by enchanters and trolls, and Beowulf, whose hero uses superhuman abilities to battle dragons. These, it was believed, were descended from older Germanic stories lost to time.

A ‘master synthesist’

One of Tolkien’s earliest Norse purchases was the Völsunga saga, which back then was available in just one English translation, undertaken by William Morris and Icelandic scholar Eiríkur Magnússon and first published in 1870. It features a reforged sword and a golden ring, known as Andvaranaut, the final item in a ransom paid by the gods to a man whose son they inadvertently killed after he took the form of an otter. That ring was stolen and then cursed, and another Norse ring, Odin’s Draupnir, was able to multiply itself. Both were forged by dwarves.

In these narratives, rings were often used as a metaphor for power. To share a ring with someone was to share a property with them. There was also a feudal Germanic tradition, Garth notes, of lords giving rings as rewards to their retainers. Not all rings were meant for fingers, either. In the Icelandic saga Eyrbyggja, Khuri explains, an arm-ring becomes the magical binding contract between gods and men.

It has been assumed that Tolkien’s rings were inspired by Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungs, but Tolkien was dismissive of the notion (Credit: Getty Images)

Norse sources had particular meaning for Tolkien and his contemporaries, Khuri suggests. “The often-bleak heroism, dynastic tragedy, and the apocalyptic imagination of Norse myth and legend resonated with Tolkien and many of his contemporaries, especially at a time when empires and kingdoms were swiftly collapsing during, and immediately after, World War One.” Their influence extends, too, far beyond the ring symbol. Gandalf, with his long white beard and wide-brimmed hat, his staff and cloak, recalls Odin, another spreader of wisdom and knowledge. His name is taken from a list of dwarf monikers in the mythological poem, Vǫluspá, as are several of the dwarves’ names in The Hobbit: Durin, Thorin, Fili, Kili, Oakenshield.

And then there’s Frodo. “The name derives from the Old Norse fróðr and Old English Frōda (‘wise’), and Tolkien chooses the Old Frisian spelling of the name,” Khuri explains. “Ironically, the Danish king, Fróði, is quite the opposite of Tolkien’s humble hero, as in one legend (told in Grottasöngr), he enslaves two giantesses out of greed (so they can grind out wealth from a magic grindstone). In some ways, Frodo’s eventual (magic-induced) compulsion to keep the One Ring is a dim echo of this greed, which is induced in his case by the Ring’s own power rather than any innate failing (and he is able to resist this magic until very late in the story).”

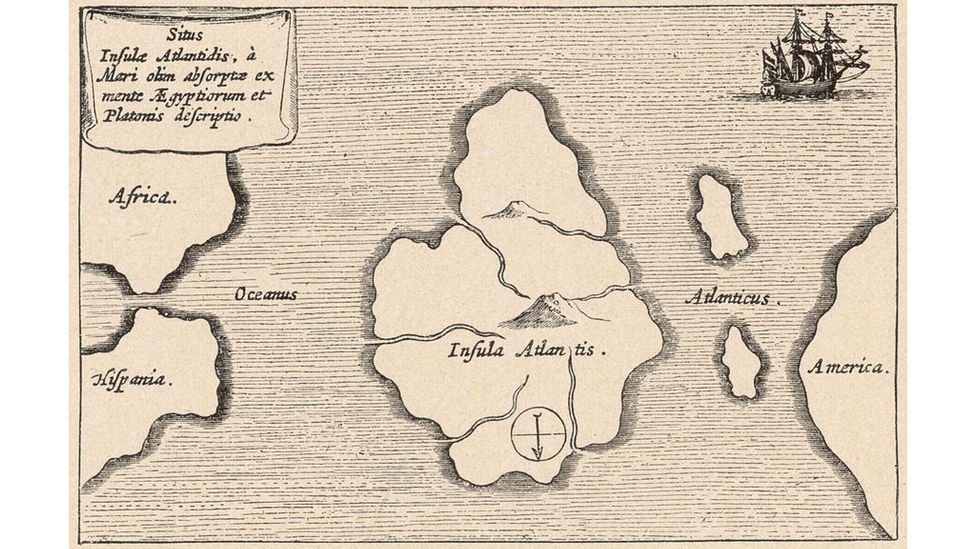

One of the underappreciated aspects of Tolkien’s genius, Garth believes, is that he was a “master synthesist”. As he goes on, “People tend to think simultaneously that he got all his ideas from Northern myth and that he made everything up out of nowhere. In fact, he found his inspirations in many places”. Or from all four points of the compass, as Garth sets about explaining in latest book, The Worlds of JRR Tolkien: The Places that Inspired Middle-earth. From the East, for instance, came medieval legends of Alexander the Great and the Egyptian infatuation with mortuary architecture that continues in the Middle-earth kingdom of Gondor. Among the least explored are those that came from the South, the classical influences that were so dominant in Tolkien’s own cultural era. The author was explicit in the role that the Atlantis legend played in shaping his Númenor, for instance, and as Garth explains, his account of its downfall – a key element of the Amazon series – builds from Plato’s account of the powerful Western sea-empire destroyed by hubris.

Plato’s Republic also mentions a ring, the Ring of Gyges, and like Tolkien’s, it bestows invisibility on its wearer. We certainly know that Tolkien was familiar with the site of a Romano-Celtic temple to Nodens, a Celtic healing god. Named Dwarf’s Hill and located in the Lydney Park in the UK’s Forest of Dean, it was first excavated by archaeologists Tessa and Mortimer Wheeler from 1928 to 1929. Tolkien himself worked on the dig and became fascinated by the hill’s folklore. In particular, he investigated Latin inscriptions, one of which brought down a curse on the thief of a ring.

Tolkien built on Plato’s account of the Atlantis legend in shaping his Númenor (Credit: Alamy)

Though Amazon’s Harfoots seem to have soft Irish accents, Tolkien often displayed a relationship with Celtic sources that was conflicted at the very least. “Tolkien did have a couple of memorable outbursts about ‘mad-eyed’ Celtic art,” Garth says. “I think they were bluster. One was when a publisher had just rejected The Silmarillion because it seemed Celtic. Actually, the Welsh language inspired Grey-elvish Sindarin, and he was fascinated by Celtic myth, even if it didn’t always have the flavour he wanted for his own mythology. His elves owe much to the Irish Tuatha Dé Danann, and his idea of undying lands over the Western ocean is straight out of Celtic myth.”

The impetus behind Tolkien’s legendarium was the creation of a specifically “English” mythology that would live up to all the others he admired, and which he drew on to make up for what he thought lacking in his native tradition. At a moment of hyper-vigilance related to cultural appropriation, his mythopoeia is a reminder that, when done well (and that part is crucial), such literary “borrowing” becomes less about assumed ownership – less, even, about homage and preservation – than about honouring the narrative’s most elemental desire to be told and retold, again and again. He succeeded so well that his legendarium has arguably now become a mythology of its own, there for the plundering by other writers, screenwriters included.

Meanwhile, hardcore Tolkien lovers have been adding another layer of meaning to the ancient symbolism of the rings. As Garth says, “It is astonishing that some fans actually marry with replicas of the curse-engraved One Ring ‘to bring them all and in the darkness bind them’.”

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power premieres on 2 September on Amazon Prime Video.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.