The images that fool the mind

In Which Is Which? (1890) by the little-known US artist Jefferson Chalfant, two identical postage stamps sit side by side above a faded newspaper clipping. The artwork looks like a collage, but one of the stamps is authentic, the other a painted replica. And the clipping, which reads, “Mr Chalfant pasted a real stamp beside his painting” – true enough – is a self-referential fiction that never appeared in any newspaper. This one small work “proffered two new conceits: faux collage and fake news”, the curator Emily Braun writes in a catalogue essay for Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition, a ground-breaking exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

More like this:

– Five paintings that show how we see

– The Japanese craft that helps us heal

– The great conspiracy of ancient art

Hanging next to the Chalfant in the show is Juan Gris’s Cubist collage, Still Life: The Table (1914), also full of sly jokes about art, illusion and reality. A clipping from the masthead of the newspaper Le Journal is folded so it appears as Jou, from the French jouer, to play. Beneath that a headline reads, “Le vrai et le faux,” the true and the false. Gris couldn’t be plainer about the teasing mind game he is setting up.

Paintings by trompe l’oeil artists of previous centuries are displayed alongside 20th-Century Cubist works at a new Met Museum exhibition (Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

These two works capture the essence of the exhibition, which makes a connection almost entirely overlooked until now, linking the iconoclastic Cubist trio of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Gris to the playful, trompe l’oeil (literally translated as “deceives the eye”) paintings of the past, many by artists ready for rediscovery. The show does not posit the direct influence of specific earlier works on Cubism, but examines their echoes in the early 20th-Century movement, from its embracing of still life to including unreliable texts. And all these artists use their optical tricks purposefully, to engage viewers in questions of truth and falsehood, issues that make the exhibition perfectly suited to our own age, when facts themselves are in dispute.

Trompe l’oeil reached its height in 17th-Century Europe, in paintings so realistic that the objects in them seem to be projecting forward from the canvas into the viewer’s space, close enough to touch. In a common motif, straps seem to be physically holding up various objects – such as sheet music or letters – on a display board, when the entire image, wooden frame included, is actually a painted illusion. The Cubists, of course, did the opposite, fracturing images to grasp an object’s essence. In her memoir Life With Picasso, Francoise Gilot quotes the artist as saying, “We tried to get rid of trompe l’oeil to find a trompe l’esprit. We didn’t any longer want to fool the eye; we wanted to fool the mind.” But a major point of the exhibition is that mind games questioning the nature of reality and of art itself were already there in the most ambitious 17th-Century trompe l’oeil paintings. “Any mimesis is not real, despite how real it might look,” Braun tells BBC Culture. Trompe l’oeil, she says, offered a “sophisticated and philosophical discourse in the Baroque period, and then again when the Americans took it up in the 1890s,” a pattern the Cubists were heir to.

The visual trickery may be fleeting, but it is often dazzling. Two of the show’s most beautiful and elegantly composed paintings are by Cornelius Norbertus Gjisbrechts, a court painter to King Christian V of Denmark, and virtually unknown today. In his Trompe l’Oeil with Violin, Music Book and Recorder (1672), it appears that a leather strap is holding up sheet music and quill pens, below a violin dangling from a nail on a wooden board. (It is all oil on canvas.) Next to it at the Met is Picasso’s Violin Hanging on a Wall (1912), depicting a fragmented but recognisable violin against a wooden wall in a similar composition.

In Still Life with Chair Caning, 1912, Picasso creates a trompe l’oeil effect (Credit: Musée National Picasso-Paris / 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / ARS, New York)

Elizabeth Cowling, the co-curator of the exhibition, tells BBC Culture that while there is no hard evidence that the Cubists would have known the 17th-Century works, there are unmistakeable visual clues that they knew the genre. Cowling says of juxtaposing the Gijsbrechts and Picasso violins: “We wanted to do that kind of thing wherever we could, because you go into that room, and I don’t think you need any wall texts or anything. You can see that there’s a relationship.” In fact, the wall text does note, “Picasso based this composition on classic trompe l’oeil board painting.” Through the centuries, the playful spirit is just as strong a connection as the visual. Sebastian Stoskopff’s 17th-Century Trompe l’Oeil (Galatea) is a painting masquerading as an engraving attached to a board by red sealing wax. Gris’s The Marble Console (1914) includes bits of mirror, reflecting viewers’ own faces in fragmented form, like a do-it-yourself Cubist selfie.

Cognitive conflict

As in magic, viewers of trompe l’oeil know they’re being deceived, and are in on the joke. And there may be something hard-wired in our attraction to those tricks. Gustav Kuhn, Reader in Psychology at Goldsmith’s, University of London, studies cognition and illusions, specifically in magic. No one really knows why we like to be tricked, he says, but he speculates that the attraction comes from “some sort of deep-rooted cognitive mechanism that encourages us to explore the unknown.” Studies of infants point in that direction. “Cognitive conflict is at the essence of magic,” he says. If you hide an object, then reveal the empty space where it was, “For really young infants, they don’t have a concept of object permanency, and so it doesn’t violate their assumptions about the world and they’re not really that interested. However, after the age of about two, where this violates their assumptions, they become captivated.”

As magic often is, 17th-Century trompe l’oeil was immensely popular but regarded as a cheap trick, looked down on by connoisseurs as a “lower” art form. Cowling says that its status as “a kind of outsider art” is just what the Cubists liked about it, part of the transgressive nature of their work. Unlike the artists of the Paris salons, they defiantly used ordinary materials like manufactured wallpaper, and referred to commonplace objects such as playing cards and cheap bottles of wine. Braque, who came from a family of house painters, learned early on to simulate the look of wood, a skill he brought into his Cubist works, including Fruit Dish, Ace of Clubs (1913). Using working-class materials and references, Cowling says, could be seen as “a kind of assertion of the necessity of being of your time, rooted in reality,” even as their art grew less and less mimetic.

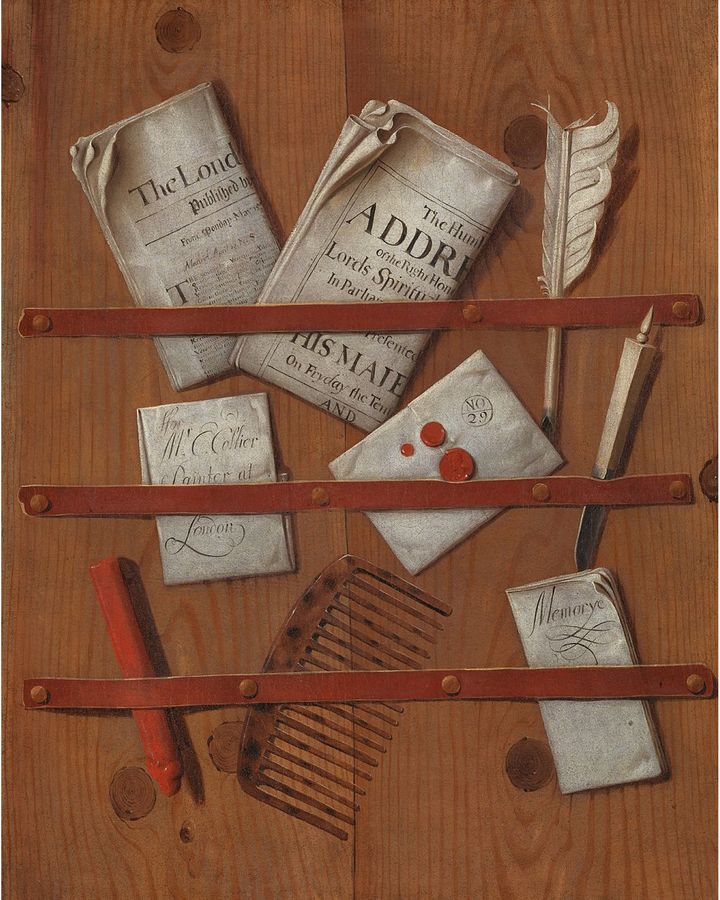

Edward Collier’s A Trompe l’Oeil of Newspapers, Letters and Writing Implements on a Wooden Board, circa 1699 (Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art/ On loan from The Tate)

The reality of society and politics is never far from the art in this show. Edward Collier’s 1699 Trompe l’Oeil of Newspapers, Letters, and Writing Implements on a Wooden Board reproduces The London Gazette and a pamphlet commenting on the Glorious Revolution. But Collier tweaks the spelling and words in the texts they are based on. Braun says, “One of the throughlines in this exhibition from the past to the present is about making us aware that things are not necessarily as they appear to be visually, and that just because something is printed, even more so digitally now, that it may have been fiddled with. Not all news is news, it’s also opinion.” Responding to an unsettled world creates a connection between the artists in this timely exhibition and those working today. Braun says that NFTs (non-fungible tokens) point to questions of authenticity and value, issues the Cubists toyed with. Picasso sometimes stencilled his name on a work, or painted it to look like a stencil instead of signing it. Does that make the art less valuable or authentic?

And Subradar: The Deceptive Image In the Screen Environment, an exhibition at the Laure Genillard Gallery in London earlier this year, considered how illusion is used today, when screens are almost overtaking reality. Jim Cheatle, a painter and sculptor who curated the show, tells BBC Culture, “I deliberately didn’t put trompe l’oeil in the title because I didn’t want [to reference] the old idea of trompe l’oeil” – in other words, as a simple visual trick. Visual illusions are even more complicated and metaphorical after post-modernism, according to Cheatle. Andrew Grassie’s painting of an art warehouse, Flat Packed Art Fair, could be taken for a photograph. In fact, the photorealist painting is based on an actual photo, and Cheatle points out that there is an added layer distancing us from reality when we’re looking at an image of that painting on a computer screen.

Jim Cheatle’s painted cast of 2021 was displayed in a recent exhibition that considered how illusion is used today in our screen-dominated world (Credit: Jim Cheatle/ @jimcheatle)

Cheatle’s own painted cast of an envelope full of paint is called Please Find Enclosed the Remainder of the Paint You Lent Me: An Intimate Note on the Absurdity of Painting. He says he intends the sculpture to register metaphorically, encouraging the viewer to engage with his work and consider the meaning of painting itself. Cheatle adds, “You could see the world we live in now as Cubist in nature, fragmented with opposing views and perspectives given to us all at once, except instead of returning us to some flat empirical reality it attempts to replace it.”

When Picasso talked about fooling the mind, Gilot writes, he went on to say that the Cubists wanted to jolt viewers by displacing objects from their usual meaning. A newspaper becomes a bottle. “This strangeness is what we wanted to make people think about, because we were quite aware that our world was becoming very strange and not exactly reassuring,” he said of the time Cubism began, as World War One was looming. The 2022 world that questions facts has its own strangeness, a connection the Met show invites us to consider.

Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art until 22 January 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.