‘The emojis of the 19th Century’

Flowers have a longstanding tradition as a means of emotional expression. When we wish to convey our affection, joy or condolences, and words won’t suffice, we rely on their beauty. Through the art of floriography, a coded means of communication more commonly referred to as the language of flowers, emotional intimacy has been allowed to flourish where it may otherwise be repressed. According to the Royal Horticultural Society, it’s a practice that dominated Victorian culture in England and the US, and, despite being largely forgotten for decades, is steadily gaining popularity once more.

More like this:

– The vintage French style resonating now

– The hidden meanings in wearing black

– Eight nature books to change your life

One of the most prominent examples of recent floriography is King Charles’s choice of funeral wreath for his mother, the late Queen. Bound by a tradition that is steeped in keeping emotions concealed, he expressed his sense of loss through his choice of blooms; myrtle for love and prosperity, paired with English oak to represent strength. To the uninformed, the wreath stood alone as a symbol of familial grief, its meaning derived from its presence not its substance. It was only by analysing the stems that the breadth of his emotions could be better understood.

Such poignant personalisation is part of a cultural foundation we all share. The tradition of floriography has always been there, but these days is a shadow of its former self – many know that a bouquet of roses symbolises romance, for example, but few know why. We might not perceive certain stems as positive or negative as the Victorians did, but we do still know that certain blooms better suit certain occasions. An understanding of flowers’ meanings, however, can help us progress from the simplicity of sending a bouquet based on only its beauty to tapping into a deeper and more nuanced emotional intimacy.

“Flowers, as gifts or for special occasions, can be all the more thoughtful when using the language of flowers. This could be based on the colour, or the type of the flower, or both,” explains Harriet Parry, a florist for Bloom & Wild. “Floriography has been around for thousands of years, but we still have customers today asking for flowers that mean something special to them, either personally or through their symbolic meaning.”

How floriography influences our decisions has enabled florists, like Bloom & Wild, to make some fascinating observations. For one, they have recorded that 29% of people select their blooms based on bouquet colour, with red being the most popular choice. The colour of passion, red is universally recognised as an expression of love. Pink, however, has a myriad of meanings depending on where you live; in Thailand it’s symbolic of trust, while in Japan it’s believed to be a symbol of good health. In a single hue there’s a variety of symbolism, yet this only begins to scratch the surface of floriography.

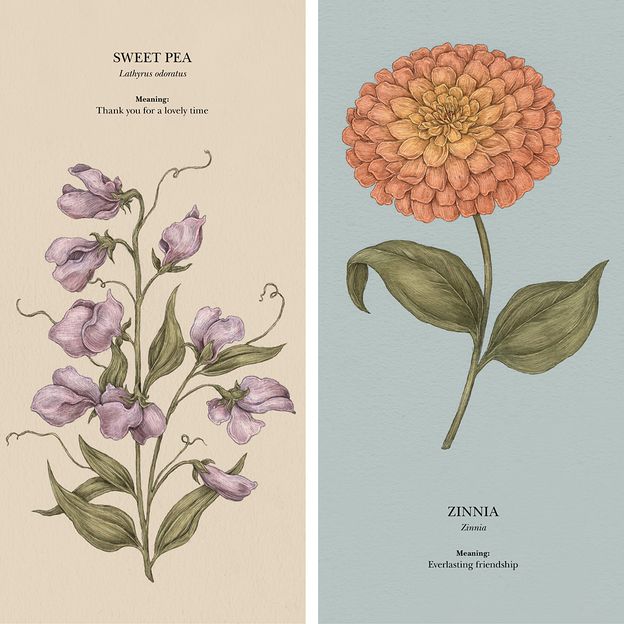

Take the sweet pea, a summertime flower that comes in an array of colours, but whose meaning remains the same: as a token of thanks. In the Victorian era, sweet peas were the go-to gift when thanking a host for a wonderful time, a gratitude that could be expressed even further by pairing it with other stems. If paired with zinnias, a flower that signifies everlasting friendship, your bouquet would help differentiate between casual acquaintance and dear friend.

But like everything in this world, for a good there is a bad, with some flowers used to represent negative feelings towards the recipient. You might think yellow carnations are beautiful, but they have a long history of being a symbol for disdain. Another flower also best to avoid is the buttercup, its yellow petals synonymous with childishness. And it was long considered inauspicious to place red and white plants together, with the belief that this combination foretold death still held by some.

The significance of all these codes and connections is explored in An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers by floriography expert Jessica Roux. Symbols of all kinds have long been part of culture, she tells BBC Culture. “Historically, we’ve been using symbolism since the beginning of our human history, working in meanings of stylised icons and hieroglyphics based on characteristics and ideas we see and experience every day.”

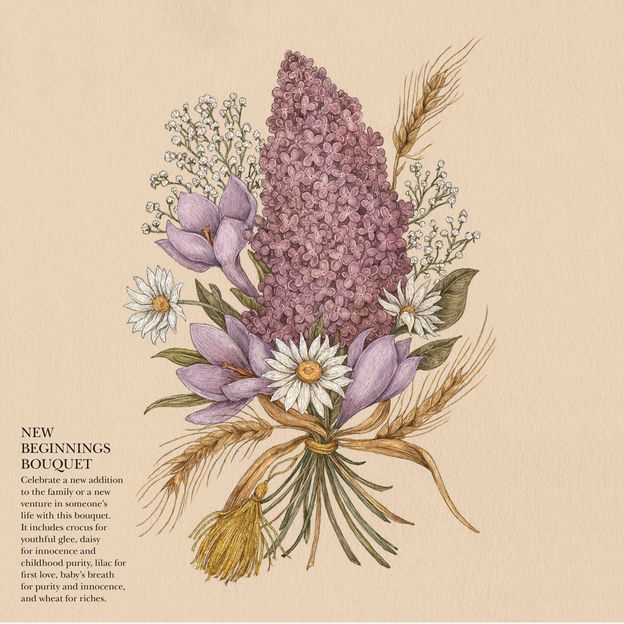

In her book, which has recently been adapted into a calendar, Roux explores the long, multifaceted development of floral language. “Flower meanings were taken from literature, mythology, religion, mediaeval legend, and even the shapes of the blooms themselves. Often, florists would invent symbolism to accompany new additions to their inventory, and occasionally, flowers had different meanings depending on the location and time.”

Although our modern-day use of floriography comes from a different place, we’re not too unlike our Victorian ancestors in our desire to only share certain aspects of ourselves. Most of us might not be trapped by repressive etiquette, but we are still bound by the perception of others. “I wouldn’t say we’re living in a similar repressed world of etiquette today,” says Roux. “But I do think we present only certain sides of ourselves online.” During the Victorian era when “stiff upper lip” was the expected societal decorum, the language of flowers was a means of bypassing repressive etiquette. Roux explains: “The Victorian language of flowers – also called floriography – emerged as a clandestine method of communication at a time when etiquette discouraged open and flagrant displays of emotion.”

Say it with flowers

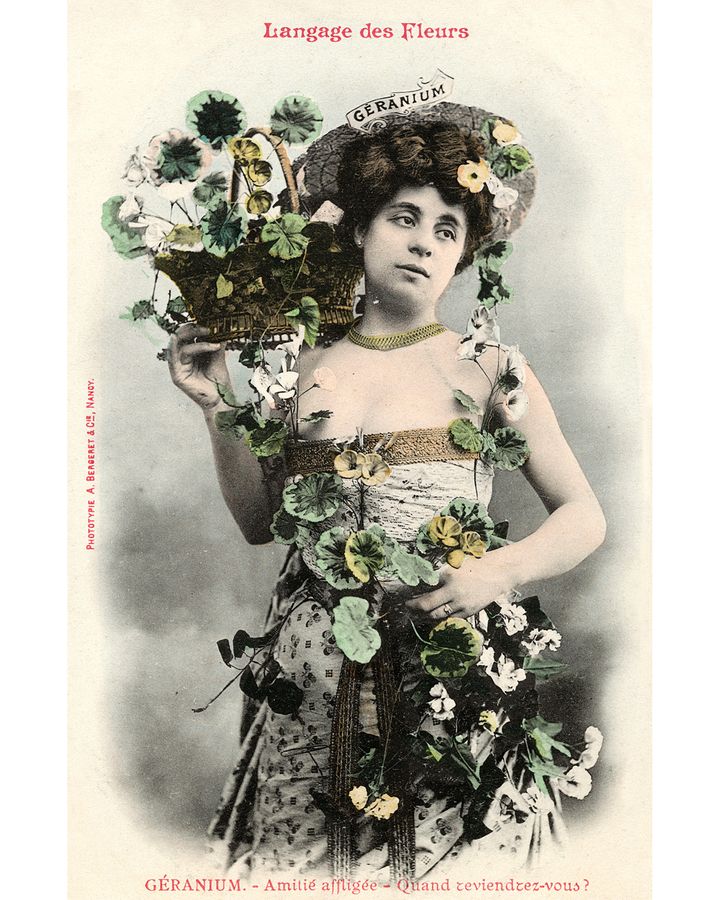

Charlotte de la Tour’s Le Langage des Fleurs, published in 1819, was the first book of its kind that detailed the immense symbolism of flowers. This book had such a profound impact on 19th-Century Western society that scholars cite it as a valuable artefact in understanding the traditions of the time.

Although the practice filtered through the social classes, it was primarily popular with women of the privileged classes – a demographic that, while in a position of financial privilege, was still regarded as inferior to its male counterpart. In a time when women were not encouraged to be outspoken, these floral accessories allowed them to communicate with their peers, offering a means for them to speak out without impeding their societal status.

“Young women of high society in this era embraced the practice, sending bouquets as tokens of love or warning, wearing flowers in their hair or tucked into their gowns, and celebrating all things floral.” Roux explains. “Many of them created small arrangements of flowers, called tussie-mussies or nosegays, by combining a few blooms in a small bouquet. Worn or carried as accessories, these coded messages of affection, desire, or sorrow allowed Victorians to show their true feelings in an enigmatic and alluring display.” Tussie-mussies were also thought to help ward off disease.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, particularly once World War One started, the art of floriography was largely lost. In a society fractured by war, austerity became the language everyone spoke, leaving in its wake the obsession with aesthetically elegant flowers.

Nonetheless, the memories of those floral customs, so deeply woven into Victorian culture, still resonated; floriography still permeated literature, ensuring the tradition was always in the periphery. Most notably, floriography plays a key role in Edith Wharton’s 1920 novel The Age of Innocence, set in the Gilded Age of New York.

Centred around an upper class couple’s imminent marriage, Wharton’s story explores the intricacies of societal mores in 1870s New York, a salacious landscape of gossip. Wharton was able to tap into the complexities of high society through an understanding of the era’s traditions. Consequently, the use of flowers plays an important role in the narrative, with the character of May always sporting white blooms.

While lily-of-the-valley blooms are used to reference May’s innocence in worldly matters, in stark contrast, there’s the character of Ellen, May’s cousin, who is associated with yellow throughout the novel. Archer, May’s betrothed, sends Ellen yellow blooms because he believes them fitting of her confidence and worldly experience. In Archer’s eyes, Ellen is an exotic, knowing woman, with the brightness of yellow capturing that belief. The continued juxtaposition between white and yellow cements the notable differences between the two women, an important thread that would be lost without the language of flowers.

Later, in the 1980s, Margaret Atwood drew on the symbolism of flowers in her 1985 dystopian classic The Handmaid’s Tale – red tulips were symbolic of the handmaids’ fertility as well as their confinement, for example. And even today, fiction still uses floriography as an important narrative tool. Barbara Copperthwaite’s Flowers For The Dead may be a thriller, but at its heart is the language of flowers, with the killer courting his victims through their varied meanings. Although clearly more chilling than Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, Copperthwaite’s story shows how these coded messages still resonate – they have a timelessly irresistible allure.

By welcoming the tradition of floriography back into wider culture, we can explore the depth of our emotions in unique ways. It becomes a postmodern means of communication, able to grow as we do, its symbolism steeped in tradition but open to change. “I’ve heard Victorians’ usage of floriography compared to how we use emojis today to communicate in messages,” says Roux. “They can vary in meaning depending on who’s using them, the context of how they’re being used, and with what other emojis (or, for the Victorians, flowers) we combine them with.”

We can talk without typing a single word. Send a heart here, a fire icon there – emojis speak through their aesthetics, a secret language all their own. Flowers are no different. They’re merely the emojis of the 19th Century, still filtering through after all this time.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.