The British author loved in India

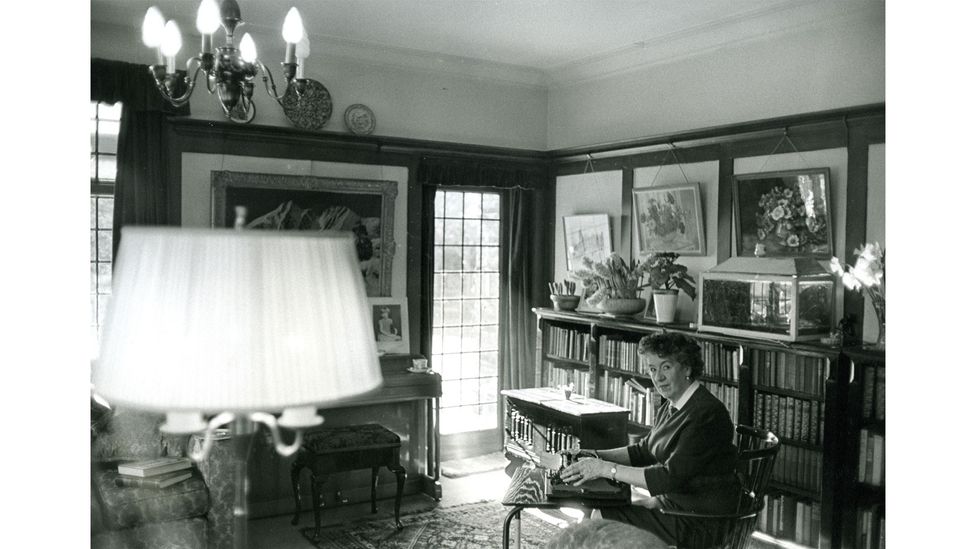

On a rainy, windswept morning in August 2021, in the Western Indian city of Pune, Alisha Purandare (35), a former German language tutor and parenting blogger, witnessed a rather heart-melting sight. Her 74-year-old mother-in-law and her eight-year-old daughter were sitting shoulder-to-shoulder on a sofa, reading in companionable silence. They were immersed in a world of mystery books written by the British author Enid Blyton.

More like this:

– The fairy-tale myth that endures

– The 26 best books of the year so far

– The mysterious ancient culture for now

For Purandare, who owns a vast collection of 300 books authored by Blyton and describes herself as a “superfan”, it was a special moment. She’s been hooked on Blyton since the age of six, when she received her first two paperbacks – possibly pirated versions of a Famous Five and The Folk of the Faraway Tree – as a gift from her uncle. It didn’t surprise her that her mother-in-law, a native Marathi speaker, who rarely read other English language books, still enjoyed Blyton. “That’s the power and magic that Blyton wields in India,” Purandare says.

Long before the era of Harry Potter, Enid Blyton was a phenomenon – a worldwide best-selling author since the 1930s, with more than 600 million copies in circulation and over 800 titles translated into 90 languages. In India, especially, her popularity soared. An entire generation of Indians grew up on a steady diet of Blyton in the 80s and 90s, especially at a time when there were few other children’s books available and libraries tended to stock more British authors than any other nationality.

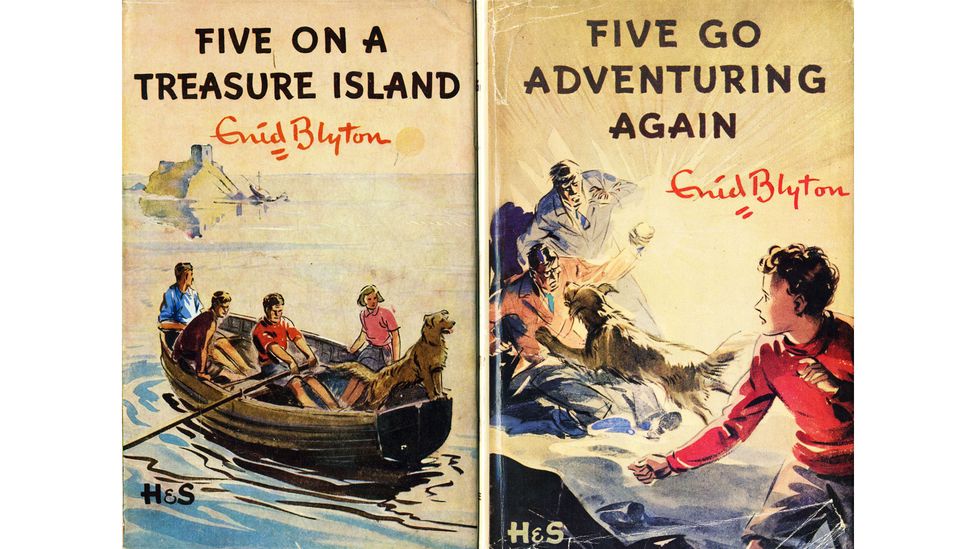

Even today, there’s a thriving demand and brisk trade in Enid Blyton across India. “Blyton is one of the few author brands whose work remains unshakable,” says Thomas Abraham, the managing director of Hachette, India. The UK division of Hachette owns worldwide rights to distribute Blyton’s books. “She’s still the third largest-selling children’s author in India in any present year after recent sensations JK Rowling, and Jeff Kinney. But if you were to consider her sales across all her books from over 70 years, I’m pretty certain she would probably be the largest-selling author, period. Because even today, her top series Famous Five [which celebrates its 80th birthday this year] sells over 250,000 copies, with the Secret Seven topping 100,000 copies year on year.” Though these two are the author’s strongest sellers, Abraham says that Blyton has several other hits such as her school series (Malory Towers, St Clare’s, Naughtiest Girl), mystery-adventures (The Five Find-Outers, the adventure series, the secret series, the Barney R mystery series, The Adventurous Four) to the family and farm adventures (Willow, Cherry Tree, Mistletoe).

Younger readers are drawn to her series, from Amelia Jane to the Faraway Tree. “She was by far one of the most prolific writers in the world,” says Abraham. “Apart from the clean, wholesome, value-educating appeal… her enduring popularity here is threefold: first there’s nostalgia as most parents start their kids off on Blyton reliving their own childhoods, then there’s the storytelling itself, from mystery and adventure to food feasts, and thirdly she’s of course still seen as one of the best English tutors in the world, and in India that’s key to getting ahead.”

Roxanne Noronha from Mumbai, who grew up loving Blyton’s books as a child, has tapped into that appeal. In June 2021, Noronha created a WhatsApp group to sell off the many books she’s collected from childhood. It was a life-changing move, she says, and it helped her connect to Blyton lovers not just across India, but Asia as well. Today, she’s made a career out of trading in Blyton and chasing down rare editions for collectors. “I’ve hunted down Blyton books piled up with second-hand dealers in dusty, narrow lanes, chanced upon reading nooks in neighbourhood restaurants and cafes and in old run-down local libraries. Finding a new edition and sharing it with like-minded collectors is an adventure and a joy,” she says. So far, she’s sold more than 500 books, a mix of paperbacks and rare first editions.

A rocky road

Noronha is aware that Blyton’s success didn’t come without its fair share of speedbumps. “Blyton once famously said that she didn’t concern herself with criticism by readers over 12; a statement with which I wholeheartedly agree,” she says.

Over the years, however, criticism for the author has been building in her native country. English Heritage noted how in 1960, Macmillan refused to publish Blyton’s novel The Mystery That Never Was, because of a “faint but unattractive touch of old-fashioned xenophobia”. It would go on to be published by Harper Collins. In 2019, the Royal Mint had proposed to put Enid Blyton’s image on a 50-pence coin to commemorate the 50th anniversary of her death, but those plans were cancelled out of concerns over her outdated views on race and gender.

Blyton’s fans in India aren’t blind to her faults. The author “colonised young Indian minds far more easily than the British East India company,” says novelist and radio commentator Sandip Roy, who defended Blyton in a 2019 op-ed for one of India’s national papers, The Mint, even as he agreed with her critics. “The amazing thing about Blyton is how it shaped not just our childhoods, but an entire trajectory of our reading, starting from when we first began to read as children (with the Noddy series), well into our teens (with the Malory Towers and the Famous Five adventures),” says Roy. Very few children’s writers could cover that much ground during one’s growing years, and that’s why her influence was so oversized, he feels. In a 2021 essay for The Times of India, Roy wrote: “Blyton’s greatest accomplishment as a writer might have been not in her home country of England but in the spell she cast over its former colonies, especially India. She colonised us with crumpets and make-believe.”

An unexpected outcome of this steady diet of Blyton were the larger-than-life impressions of England that it painted for Indian readers – Blyton even made bland English food sound utterly delicious, says Roy. “I grew up reading about potted-meat sandwiches for picnics, scones for tea, and yearned to see snowdrops and buttercups, only to go to England in my late teens and to find all of that… quite underwhelming,” he says.

However, Blyton did fill his childhood years with excitement and a sense of adventure. He loved the fact that children in her books had agency – they ran away from home, could take trips on their own, living in hollow trees in woods or camping in caves. “It was worlds apart from the very sheltered upbringing I had in Kolkata,” he says.

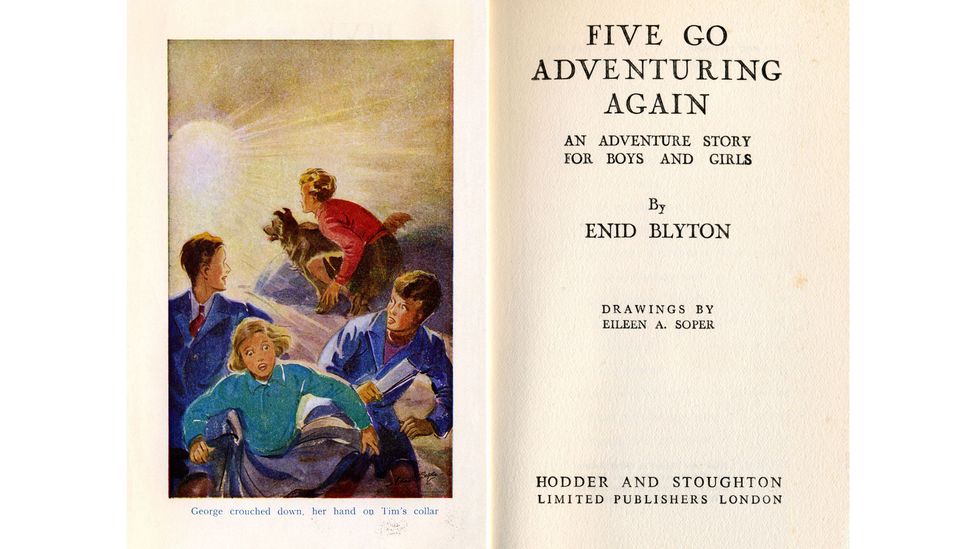

Reading Blyton as an adult, says Purandare, was a very different experience. She couldn’t overlook the many disturbing references that she’d failed to see as a child. It wasn’t until last year, when she started collecting dust-wrapper editions from the 1960s, that she realised how much Enid Blyton’s books have been sanitised, with offensive and racist slurs changed by publishers over the years.

Some of these changes are entirely justified, she says. For instance, the book The Three Golliwogs tells the story of three of these dolls, named after offensive, racist slurs. The dust-wrapper editions of these books published in 1968 and 1973 still retained those names. In the subsequent editions of these paperbacks, these terms were sponged away, says Purandare.

Exploring older editions and comparing them to more modern ones, Purandare began to find that many of these omissions were based on gender. In the 90s edition of the standalone novel The Family at Redroofs, an entire passage is missing, she says: it’s about the instructions that a father, who is about to go on a trip, gives to his young son, when he leaves him in charge of the household. He has an older daughter, but he doesn’t rely on her. There’s a lot of casual sexism, in spite of Enid Blyton having created the character George, the star of the Famous Five, who was seen as a rebel and who rejects the tropes of gender, Purandare notes.

“Blyton did patronise women in her books a lot while playing up to populist sentiment on gender. She reinforces how a woman is supposed to be a primary caregiver, how the household falls apart without a woman at home, an irony when Blyton herself was a successful career woman who did no caretaking of her own,” she says. But expunging the books of these flaws prevents the reader from discussing them and seeing authors as a product of their times. “By completely wiping out any of the references that we feel may be politically incorrect, we’re preventing deeper discussions about these prejudices that it could spark in young readers,” says Purandare.

One critique that grew over the years was that her books clearly lacked brown and black characters. Those that were there were often looked down upon, like the gypsies in the Famous Five series, who were made out to be undesirable and petty thieves. “If her books had brown and Indian characters, we would have perhaps been more aware of the racist undertones,” says Roy. “In India [at the time], we were hardly aware of race politics and thought nothing of the lily-white nature of our books.” And for many readers, the adventure mattered more than anything else and it was what they consciously chose to focus on, he says. A current generation of readers, however, is bound to be more aware.

Bridging that void now is British Indian author Sufiya Ahmed, who has been commissioned by Hachette to make the Famous Five more inclusive for South Asian readers. Ahmed was born in Gujarat, and raised in Bolton and London. She first began reading Blyton as a child in the 80s, she says, when all the problematic references had already been removed. “Her books gave me so much pleasure, transporting me into worlds where mysteries were solved, adventures were experienced and fantastical settings were explored. I think it’s the escapism that grabbed me really and that made me a reader,” she says.

It also made her dream of being a writer. “Today, I’m just making the setting for the Famous Five’s adventures more reflective of the world that young readers live in, without changing the essence of their appeal. The Five still love the countryside and the coast, go camping on their island, and are good-hearted children who help their friends and neighbours and of course are devoted to Timmy the dog, but the new adventures are more reflective of modern times,” she says. The settings for the Famous Five adventures are now more diverse, with more people of colour in Kirrin Village, where they live.

The first book in series, Timmy and Treasure, was released in January. The second story she’s written, Five and the Runaway Dog, released in May this year, introduces Simi, a girl of South Asian heritage, and her family who have moved into the village. Simi plays a major part in the story and is also featured on the front cover. The third book, Five and the Message in a Bottle, an upcoming release slated for May 2023, includes a police chief of Nigerian heritage. A girl in a hijab is featured in images and as a village resident.

Another author – Jacqueline Wilson – has written a new story for The Magic Faraway Tree series, addressing some of the gender prejudices of the original. The book, which was published in May, retains the characters of the Faraway Tree that readers know and love – Moonface, Silky the Fairy and Saucepan Man – and introduces new characters Milo, Mia and Birdy. In the revised editions, among other subtle changes, the girls aren’t the only ones helping with domestic chores and Milo is a boy with longish hair who often wears pink.

The re-written Famous Five books have been received well by young audiences – and not just in the UK, but Spain and Portugal, too, says Ahmed. “My readers see the Britain they are familiar with, one that is multi-cultural and inclusive,” she says.

Though Blyton is still popular in India, she doesn’t hold a cultural monopoly over young minds. Indian authors and publishers have long catered to young children, and children’s book publishing in the country is going through a revolution, as publishers experiment by translating into different Indian languages and exploring new subjects. The Delhi-based Children’s Book Trust, a pioneer in children’s publishing that has been operating for 60 years, now reaches hundreds of readers in India’s remote rural villages. Pratham Books, a non-profit publisher in India, has been producing engaging children’s stories since 2004, which have been translated into 21 Indian languages, including four tribal languages. The award-winning Duckbill, acquired by Penguin Random House, has published books about Indian characters such as Chumki in Chumki and the Elephants, a story of how a young girl learns more about the wild animals who are so much a part of her home. “These are books about children from different cultural backgrounds even within India, giving children a peek into the lives of kids who are so different from them, and yet, so alike in many ways,” says the author of Chumki, Lesley Denise Biswas. “When books are written by diverse authors, their personal experiences are invaluable.”

And yet, Blyton still has the power to overcome her critics and to transfix; as Purandare discovered on that August morning, when her daughter Rumi spent long, happy hours reading with her grandmother. “It made me nostalgic,” she says. “Growing up, it was all I ever did with my pocket money: invest it in buying more books by Blyton. So, it made sense to me that Blyton was able to transcend any generational gap – to be so loved and read at all ages.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.