The bizarre plot that tricked Hitler

It’s a story so fantastic and macabre that it feels like the product of a writer’s imagination. In 1943, at the height of World War Two, British Intelligence agents hatched an elaborate scheme to convince the Germans that the Allied forces were planning to invade Greece rather than Sicily. The plan, code-named Operation Mincemeat, involved planting forged documents upon a dead body before setting him adrift in neutral Spanish waters, with the aim of the papers ending up in German hands.

The false intelligence found its way onto Hitler’s desk and was evidently believed as Germany ordered tanks divisions, artillery and boats to defend Greece, Sardinia and the Balkans. When Allied troops invaded Sicily on 10 July 1943, the Nazis were caught unawares.

More like this:

– 10 films to watch this April

– The man who hid in the jungle for 30 years

– The bus driver who stole a Goya masterpiece

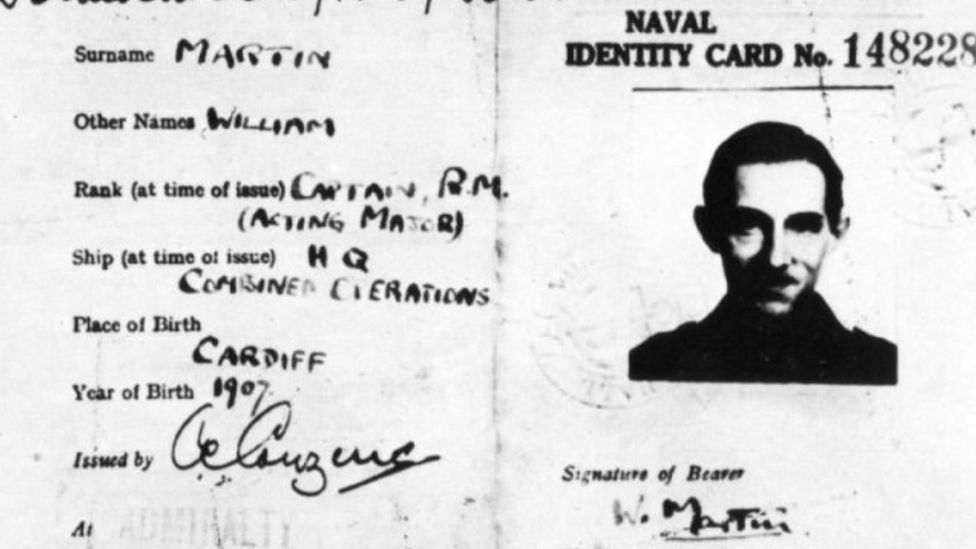

The deception succeeded, in part, because the naval intelligence officers behind it, Ewen Montagu and Charles Cholmondeley, were so invested in the fiction. They created a convincing backstory for the corpse, a whole new identity: a homeless person named Glyndwr Michael, who had died after ingesting rat poison, was transformed into William Martin, an officer of the Royal Marines. They gave him not just a name and rank, but an entire life including a fiancée waiting for him at

home.

The new Operation Mincemeat film stars Matthew MacFadyen and Colin Firth as the scheme’s two masterminds Ewen Montagu and Charles Cholmondeley (Credit: Alamy)

Author and historian Ben Macintyre’s gripping 2010 account of the story is now the basis of a film, also called Operation Mincemeat, directed by John Madden, of Shakespeare in Love and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel fame. It stars Matthew Macfadyen as Cholmondeley, the ungainly aspiring airman who was stymied both by his height and his poor eyesight and seconded to the British security service, MI5, who first suggested the plan, and Colin Firth as Montagu, the shrewd peacetime lawyer who helped develop it.

“They worked together to build this completely imaginary world,” explains Macintyre. Working alongside formidable administrator Hester Leggett and the ambitious young secretary Jean Leslie (played by Penelope Wilton and Kelly Macdonald), they sourced an ID card, a uniform, the underwear befitting an officer, and furnished Major Martin with all manner of “wallet litter”. This included a note from his bank manager, saying he was overdrawn; receipts and ticket stubs from various theatres and clubs, to demonstrate his appetite for nightlife; and, most poignantly, love letters from his beloved “Pam”, with whom he’d had a whirlwind wartime romance. They even gave him an engagement ring.

The creation of the ultimate war story

There’s a real sense that these people lived vicariously through their creation. “These were people who were unable to take part in the actual war on the battlefield, either because they were too tall, like Cholmondeley, or too old, like Montagu, or they were women like Jean and they imagined themselves into a kind of parallel underground war,” says Macintyre. “There’s something touching and remarkable about the idea of a hidden hero.”

In building a life for Martin, the Operation’s team were forced to draw on their creative resources, and needed to think like writers. And writers abound in the Mincemeat story, something the film plays up. The so-called “trout memo” – a list of potential ways to deceive the enemy which inspired Cholmondeley and Montagu – was likely written by James Bond author Ian Fleming, then assistant to Admiral James Godfrey, who in turn got the idea from a novel written by another espionage man-turned-fiction writer Basil Thompson. In the film you can see Jonny Flynn’s Fleming absorbing every outlandish detail for future use.

“I think it’s no accident, in a way that some of the greatest novelists of the 20th Century were also spies: Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, John Buchan, John Le Carré,” says Macintyre. “So much of what spies do is to create a false world and convince someone else that is true.”

This was part of the appeal for writer Michelle Ashford, who adapted Macintyre’s book for the screen, having read and loved it when it was first published. “It’s almost like a Valentine to spy stories,” she says. “And how ironic that the creator of James Bond was actually one of the architects of the story.”

“I love the notion that the whole course of the war was changed by this small group, hunkered down in a smoky, depressing, windowless basement room,” says Ashford. “That they were the ones that made the difference.”

An id card was among the items created for the fake “Major Martin” (Credit: Alamy)

Fittingly, this true story in which fiction plays a part has frequently been fictionalised. In 1950, Duff Cooper, a former cabinet minister, published the novel Operation Heartbreak, a thinly veiled version of events. When challenged that in doing so he was divulging official secrets, Macintyre explains, Duff reasoned that “Winston Churchill was telling the story after dinner every night, so why shouldn’t he tell it?” This gave Montagu the impetus to write his own version of the story, publishing The Man Who Never Was in 1953, (later the basis of a film of the same name, which added further fictional layers to the tale), which he claimed was the true version, though he altered some details – most notably that the family of the deceased man gave them their permission to use his body, which was not the case.

Now, the film’s arrival in UK cinemas (before it comes to Netflix in North and Latin America in May) coincides with the return to UK stages of a hit musical about the very same story, also called Operation Mincemeat. The show, devised by theatre company SpitLip, started life on the London fringe in 2019 and has since played several sell out runs at increasingly larger spaces.

While the songs draw on everything from Beyoncé to sea shanties for inspiration, and it features the best dancing Nazis since The Producers, the show stays true to the spirit of the story. “We really loved how much they loved creating the fiction,” says SpitLip’s Natasha Hodgson, who plays Montagu. “We really wanted to get across the joy of creation and story and narrative because that’s what we were doing too.”

Like the film, the musical conveys a sense of people getting to live out their fantasies and getting slightly carried away. At the same time, the company were aware that “we were telling a story in which the vast majority of the characters were white men at the top of the tree,” says Hodgson. They attempted to circumvent that by casting her as Montagu and having Leggett, a middle-aged woman, played by a man, Jak Malone, who gets to deliver the show’s most moving song, Dear Bill, based on the love letters written by Leggett in the guise of Pam. (“Why did we meet in the middle of a war? What a stupid thing for anyone to do.”)

The impact of song has been sharpened by the pandemic. “It hits doubly now that everyone’s been through something where they might have yearned for a loved one for upwards of two years or lost a loved one and never said goodbye,” reflects David Cummings, who plays Cholmondeley, as a sweetly geeky newt-fancier.

The forgotten man

However while it’s easy to get swept up in the romantic aspects of the story, a cracking tale of wartime espionage populated by colourful characters, what they did was undoubtedly morally dubious. To create Martin, they had to find someone who would not be missed, a body they could treat as a blank slate, as if he had never lived.

Glyndwr Michael’s identity was not revealed until 1996 when amateur historian Roger Morgan found a recently declassified document that contained his name. Rather sadly the only photo that survives of him is one of his corpse dressed in military uniform. Even now very little is known about his life, says Macintyre. He was a vulnerable young man from Wales with no living family – the film gives him a sister – most likely mentally ill, who was found in a disused warehouse in King’s Cross, having possibly taken his own life.

This unhappy element of the story is something that SpitLip was conscious of when writing their show – so that, while the musical is based on the version of events presented by Montagu and his team, “it was important [for us] to shine a light on the less ethical aspects of it,” explains Cummings.

Ashford was keenly aware of these too. In war, she says, “sometimes you’re left with a ghastly decision, no matter which way you go.” She was keen to address this in the film, the tension felt by Montagu that “what we’re doing is really questionable. But what else are we going to do? Because we’re in the middle of war and war quite often means [making] terrible choices.”

A new stage musical reinvents the story of the operation with songs inspired by Beyoncé and sea shanties, and gender-swapped casting (Credit: Matt Crockett)

The codename Mincemeat was chosen in dark humour as an allusion to the operation’s grim underpinnings, something not lost on Adrian Jackson, who as the former artistic director of Cardboard Citizens, a UK theatre company that makes work with and about homeless people, co-authored a play with Farhana Sheikh, simply and pointedly called Mincemeat, which reinstated Michael at the centre of the story,

The promenade performance was staged twice in 2001 and 2009. “We told the story backwards,” Jackson tells me. “Essentially using the same trope as in the Powell and Pressburger film, A Matter of Life and Death: a bloke turns up at heaven, dressed as an airman and with all the papers of one Major Martin, but has no memory of how he got there or who he is.”

The play sees Michael return to Earth in search of his identity. As part of his research, Jackson even managed to track down one of the undertakers who moved Michael’s body in the middle of the night. The play contained a sense of anger that a person could be deemed more valuable after death than when alive. “Telling the story entirely from his angle gave us the full pathos and dignity of his life,” explains Jackson.

“The fact of much of the acting company having had what is now called ‘lived experience’ [of destitution] added authenticity and power,” he adds.

The film includes a scene in which Michael’s sister chastises them for their callousness in using him in this way. It also shows his gravestone in Huelva, Spain, which now bears both the names Glyndwr Michael and Major William Martin, affirming that he served his country, which Ashford feels that he did. SpitLip did not want to shy away from those questions either, but fundamentally they wanted to celebrate what Montagu achieved, and its sheer audacity.

Because for all the ethical murkiness, and the sense of getting swept up in their own deception, they pulled it off. The Allies invaded Sicily as planned, but the Germans remained convinced it was a diversionary tactic. “It’s a really important moment in history,” stressed Macintyre, “because unlike most espionage stories, and I say that with all due humility, as I’ve written a lot of books about spies, this one really did make a difference, this one actually strategically altered the course of the war.”

Operation Mincemeat is out in UK cinemas now and released on Netflix in North and Latin America on 11 May; SpitLip’s Operation Mincemeat is at London’s Riverside Studios, London, from 28 April until 9 July

BBC Culture has been nominated for best writing in the 2022 Webby Awards. If you enjoy reading our stories, please take a moment to vote for us.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.