How to survive the ‘post-book blues’

In recent weeks my world has been tainted by a break-up… I’ve ended a month-long relationship with Billy Connolly, the much-loved Scottish comedian – via my audiobook app. I’ve spent hours listening to Billy reading his life story – his comedy, his music, his love of digestive biscuits, and I’m not sure what I’m going to do without his lilting Scottish tones. It was the same with past audio-based chums: Dave Grohl, Peter Frampton, Barack Obama, Roger Daltrey. And where would I be without comedian Bob Mortimer, with his relatable life story and tips for carrying “pocket meat”? (…For those who don’t know who or what Bob Mortimer is, “pocket meat” is more innocent than you think.)

More like this:

– The best books of the year so far

– The writer who predicted the future

– The overlooked masterpieces of 1922

This “post-book blues” thing is a side-effect that doesn’t seem to get mentioned much, if at all. It’s not an in-person relationship as such, but it is one forged in a unique, unwritten contract with the reader or listener – signed by your subconscious when turning to the first page, or hitting “play”.

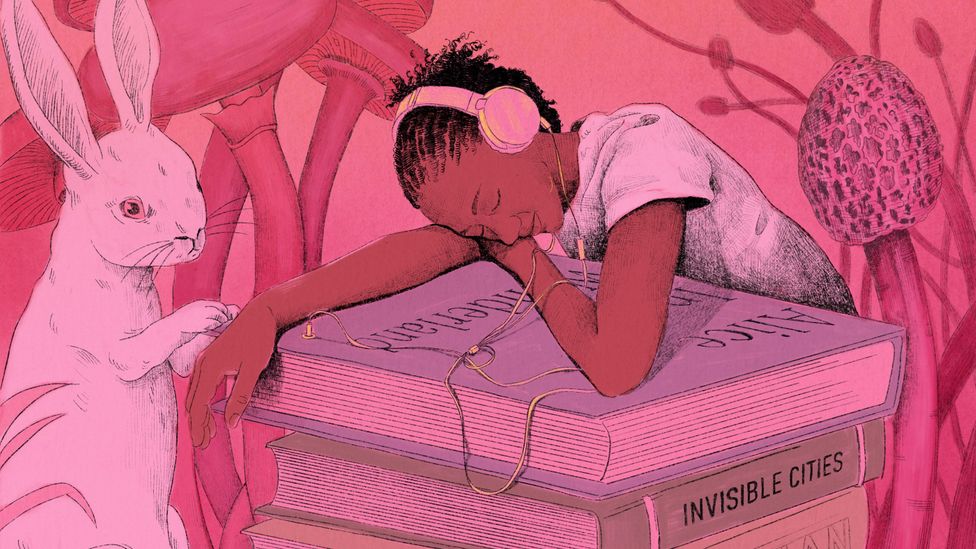

(Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

For a day, a week, or a month you actively immerse yourself in someone else’s world. You get a story, escapism, possibly even life-changing revelations. In return they get your undivided attention. But what happens when you finally re-emerge from that transaction? The longer it goes on for, the harder the end seems to be, as my recent situation with Billy suggests. How usual is this feeling? Do I let myself get too immersed? And how does one cope with those post-audiobook blues?

Bijal Shah, a bibliotherapist and author, is like a literary version of a matchmaker and counselling service in one – helping her clients find books that aid their mental well-being. According to Shah, the post-audiobook blues might be a hint of something innately human. “That is very, very common. It’s a sense of loss that you feel at the end [of a book] and you’re grieving. It’s like saying goodbye to so many friends you’ve made, because you’ve got to know this person over the course of the book and now there’s no more connection, and this is why sequels do so well – it’s that continuity.”

The Covid-19 pandemic appears to have re-calibrated many of our lives and our minds in ways we’d never thought likely. So, here in 2022, where are we heading with our yearning for personal connection? “I think the way our culture is going is that we are so focused on individualism, that we are now sort of craving that collective community. My parent’s generation and their parents grew up in these communities where it was all about helping each other and less self-focused,” Shah says.

“Whereas now… we need other people to constantly affirm us because we don’t have those natural connections that our parents’ and our grandparents’ generation had – that sense of community where we knew our place, we knew who we were, we knew where we belonged. I think we’re lacking that, currently. I think books probably fill up that space because they’re forging [that sense of community] by vicarious connections, so filling those holes, perhaps.”

Leap of the imagination

On the face of it, it isn’t surprising that we’re more in need of community, a connection, than ever before. But it’s always been in our nature to be attracted to these aspects of life. So, what exactly draws us into a story? Cognitive psychologist Keith Oatley, from the University of Toronto, is the author of Such Stuff as Dreams: The Psychology of Fiction, which looks at how works of fiction interact with the brain and imagination.

(Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

“I think it is a natural reaction,” says Oatley. “People choose books with which they can resonate. And so you can recognise these aspects [of a story] within yourself. What writers do is they offer suggestions, and then we as readers or audience members or listeners take them up and then imagine them for ourselves.” While the author is responsible for creating the work, argues Oatley, reading it is “a shared activity”.

“What the author or writer does is provide maybe one third, but we ourselves, as we engage in that, we provide two thirds. Because what we’re being offered are not descriptions, they are suggestions which we then take up and imagine for ourselves. And our emotions are our own as well,” says Oatley.

All we need is a whiff of description in a story, and our brain picks up the baton and runs with it. Before you know it, we’re hooked and we have created our own, partly self-invented, fantasy land. But suggestion runs deeper than just epic mental Minecraft, as Oatley explains. “The word that I use is ‘enable’ because the person actually has to lean in a bit. I think the thing about fiction is it’s an invitation for the reader which that person has to take up, and then is enabled to make up their own mind.”

Oatley’s current focus is on the types of genre that might elicit this power to alter our psyche. “We’re trying to get into what engaging with fiction really does for people. And it isn’t just any old fiction, literary fiction enables people to think more deeply, and we’ve also done studies in which reading a literary piece of work enables people to change within themselves. And so rather than persuasion, where someone says ‘you ought to think this’ or ‘you better do that’, what literary art does is it enables people to change within themselves, but in their own way.

(Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

“In another study that we did, which we wrote about in the New York Times, [we found that] reading Chekhov’s most famous story The Lady with the Little Dog enabled people to change. But then we measured the amount of change of their personalities, and rather than everybody’s personality changing in one direction, everybody changed in their own way,” says Oatley.

As Shah can attest, one of literature’s strengths is its ability to aid and enable those with mental health issues, to help to deal with certain aspects of how they feel. “The key with any form of art therapy,” she says, “including books, is that ability to explore your own emotions from a safe space, and literature is definitely a medium that allows you to do that because it allows you to step back, but still explore painful emotions through another object, so there’s that distance. That in itself is something that’s quite powerful for any form of art therapy and particularly for literature. It’s holding up a mirror almost.”

But what about empathy? That’s surely a big driver to that feeling of mourning when the final chapter has played out? One key to emotional connection is the all-important protagonist. It’s why some people deliberately don’t finish certain books, because either they may not want to know what happens to a favourite character, or the end of a special read is worth prolonging…forever.

Oatley explains: “It’s a little bit like meditation. When you’re reading or listening to a book you put aside your current day-to-day concerns and take on the concerns of a character, usually a protagonist. So, you experience emotions, but they’re your own emotions in that situation.”

(Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

To apply what I’ve discovered so far to my own scenario, Billy and his life are in effect living in my head, but it’s essentially my own reboot of his story. I’ve invested my own very real emotions in his journey, and maybe it’s even changed my character in some way.

Fiction and non-fiction stories have always been there to help catch our fall during troubled times. It’s pure, healthy escapism. No matter who wrote the book, we each absorb them and our brains do the rest. Best of all, you might even meet some new friends, no matter how fleeting or one-sided your bond, along the way. For me, Billy Connolly and his life story will now be chalked up as time very well spent. Perhaps the best way to get over the post-book blues is to be grateful for what you’ve learnt, and enjoy where your imagination has taken you.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.