Black British experience laid bare

Black British experience laid bare

(Image credit: Tam Joseph/ Wolverhampton Art Gallery)

The often stark reality of Caribbean-British life has been reflected in art over the decades. Precious Adesina explores the remarkable artworks that reveal some uncomfortable truths.

I

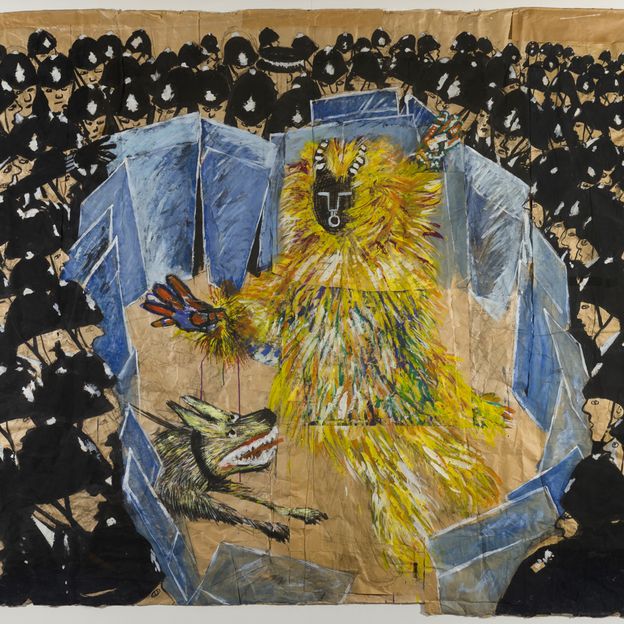

In Spirit of the Carnival (1982) by Tam Joseph, a masked performer wearing a fiery yellow ensemble is surrounded by a sea of riot police. The painting depicts a Sensay, a person in a traditional Dominican masquerade costume, with their hands stretched out as an angry dog breaks through the circle the officers have formed around the man. Joseph remembers going to Notting Hill Carnival with his parents growing up; the place being filled with friends, family and people of Caribbean heritage who were looking for something that reminded them of their culture. But it was the tension between carnival-goers and the police that stood out to him, inspiring this composition.

More like this:

– Britain’s first black aristocrats

– The real history of Notting Hill

– The artist skewering white privilege

With the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement over the past couple of years, Joseph’s work feels as if it could have been made today. However the artist wants people to feel the excitement and vibrancy of the Sensay, rather than getting caught up in socio-political discourse.

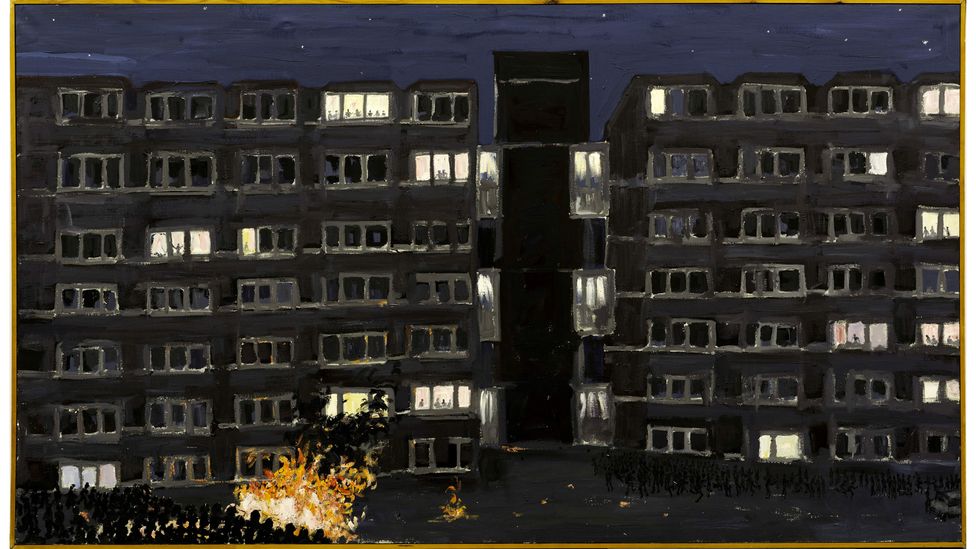

The Sky at Night (1985) by Tam Joseph is among the artworks displayed in Tate Britain’s Life Between Islands exhibition (Credit: Tam Joseph)

But, walking through Life Between Islands at Tate Britain, an exhibition about Caribbean-British art from the 1950s until today – where the painting can currently be found – it’s hard to ignore the artworks that conjure up conversations around race – discussions that are still as prevalent today as they were 70 years ago. This is especially the case after the Windrush Scandal in 2018, and the 2020 global protests following the murder of George Floyd in the United States.

Alex Farquharson, director of the gallery and co-curator of the exhibition, alongside the art historian David A Bailey, says that he started working on Life Between Islands six years ago, before both incidents. “Black people in Britain, including artists in the exhibition, have often had to deal with extreme hostility and societal discrimination,” he says, noting that he doesn’t see Life Between Islands as deeply political. “Some of the documentary photography reflects that depressing reality and the courageous struggles against it, but there are as many photographs in the exhibition from the 60s, 70s and 80s that convey creativity, joy, intimacy and community.”

Spirit of the Carnival (1982) by Tam Joseph is a powerful depiction of Notting Hill Carnival (Credit: Tam Joseph/ Wolverhampton Art Gallery)

Despite this, the relationship between black people and the police is apparent on multiple occasions, as does the discrimination against black people in Britain, especially around the time of Joseph’s paintings. “The early work of the black arts movement in the 1980s was often unsparing in confronting the contemporary realities of racism in Britain,” Farquharson says. This was particularly the case with the BLK Art Group, a collective of young black artists founded by Eddie Chambers in 1979. The curator points out Chambers’s The Destruction of the National Front (1979-1980) a four-part collage that sees the Union Jack transform into a swastika. “[It] epitomises that early phase of the black arts movement,” he says. “This was at the height of the ‘popularity’ of the National Front, who would parade with impunity through black and Asian communities.”

“Police harassment of young black British people was routine, unemployment very high, and the political rhetoric often inflammatory – black and Asian people were described as having ‘swamped’ Britain by the Prime Minister at the time,” he adds. “The pent-up anger boiled over in major riots, or uprisings, in Brixton, Toxteth and many other urban centres in 1981.”

Isaac Julien’s documentary Territories (1984) is a montage of beautiful scenes alongside news reports (Credit: Courtesy of the artist/ Victoria Miro, London/ Venice/ Isaac Julien)

Isaac Julien’s documentary Territories (1984), made while Julien was still a student, looks at the role of the media in portraying carnival, using a montage of beautiful scenes alongside archival news reports. “The music was dismissed as noise, the dancing as… sexual misconduct and debauchery,” says one narrator, before an interviewee discusses how police presence at carnival in 1976 caused uprisings. “The police attitude is aggression against sound systems on [street] corners because they see any gathering of young black people as threatening,” the man says.

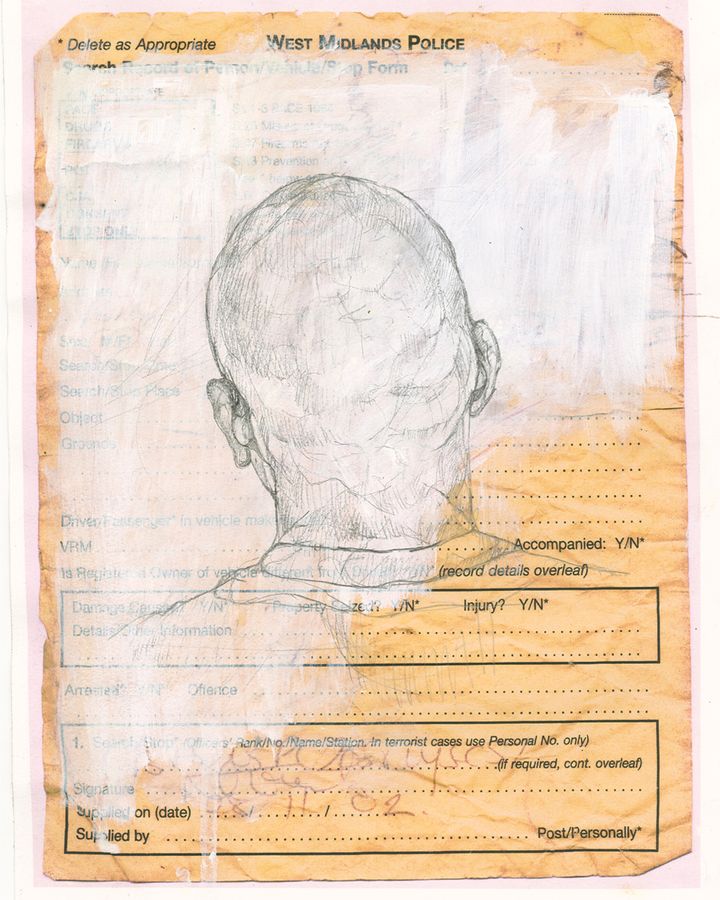

More recently, Barbara Walker’s drawings in the exhibition look at the misrepresentation and stereotyping of black communities, but from a more personal perspective. Louder than Words is a series created between 2006 and 2009 about Walker’s son Solomon, which features copies of police dockets that were given to him while walking around their hometown Birmingham, during UK stop and search procedures (where police frisk members of the public). Drawings and paintings of her son or the places where he was stopped are superimposed on top of these documents or newspaper articles. One headline reads “In The Wrong Place At The Wrong Time,” alongside a detailed charcoal sketch of Solomon looking plainly at the viewer. “I was intrigued about the almost ritualistic procedure of stop and search, but most of all, I wanted to make art about the dreadful ways in which my beloved son was being treated,” Walker tells BBC Culture. She believed that by stopping her son, the police reduced him to a deviant. “Why should he be roughly treated, as though he were a convicted criminal?”

Barbara Walker’s My Song (2006) is one of a series exploring the racial stereotyping of the artist’s son (Credit: Richard Wilson and Kelly Smith/ Barbara Walker)

Farquharson says that the exhibition shows that Britain has come some way in the treatment of black people, albeit not far enough. “The black contribution to British culture is stronger, more visible and more celebrated than at any time prior, especially in recent years,” he says. “But the events of the past few years were powerful reminders that racial injustices continue, often in ways that are invisible to white British people – Black Lives Matter has acted as a powerful wake-up call in that respect.”

The exhibition Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now is at Tate Britain, London, until 3 April

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.