A misunderstood horror masterpiece

The story of Ganja & Hess is just as compelling a tale as the film itself. Written and directed by Bill Gunn, and released in New York on 20 April, 1973, the black vampire movie has lost none of its power over the past 50 years. It artfully depicts a wealthy anthropologist Dr Hess Green (Duane Jones), who is stabbed by his assistant George (Gunn) with an ancient African ceremonial dagger before George kills himself. The dagger turns Hess into a vampire, and further complications ensue when George’s widow Ganja (Marlene Clark) comes to Hess’ home looking for her husband, and the two fall hopelessly in love.

More like this:

– Where do vampires come from?

– Films that scare in unexplainable ways

– A horror dubbed the ‘number one nasty’

The film defies easy classification with its hallucinatory visuals, rich metaphors for addiction, raw sexuality and lyrical dialogue that offers a wholly unique treatise on African-American identity. For the film critic and programmer Kelli Weston, who recently co-programmed the In Dreams are Monsters season at London’s British Film Institute, which screened Ganja & Hess, “the story has a quite classic structure for a horror film” and is founded on “the core premise of horror cinema, that what is repressed must always return”. “But Ganja & Hess is enlivened by these black characters and the tension between spirituality, addiction and the predatory nature of empire,” she adds. “Hess faces a curse from another place that he’s sort of tied to – there’s a rupture between black Americans and Africa, but a sense of feeling always bound or even haunted by it.”

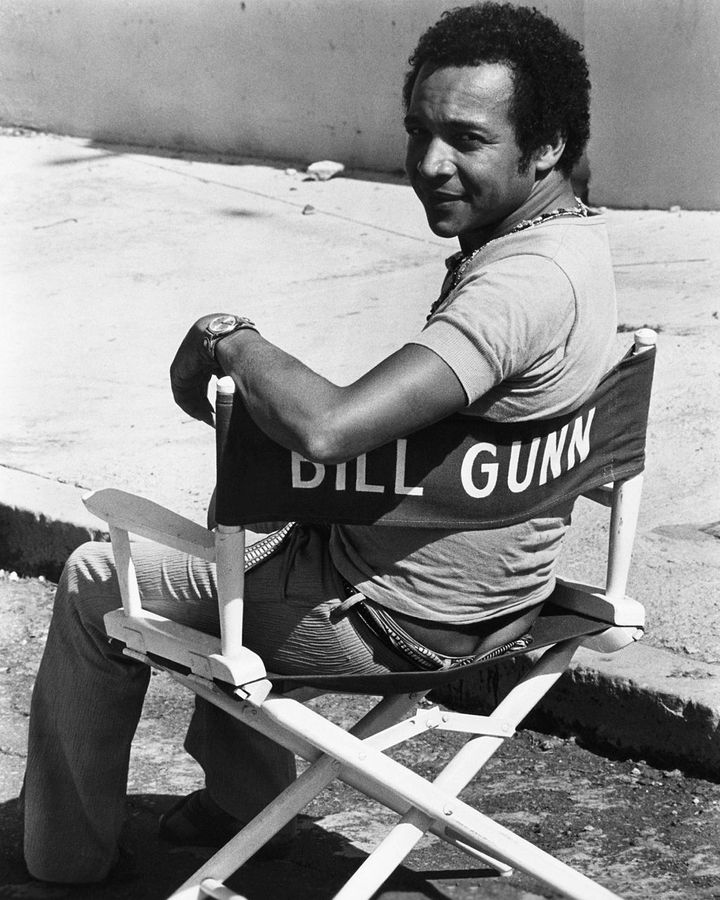

Ganja & Hess lead actor Duane Jones (pictured left) had previously made his name in another horror classic Night of the Living Dead (Credit: Kelly-Jordan Enterprises)

But, while Ganja & Hess is nowadays widely praised, the journey that Gunn’s film has had to gain due respect is infamous, having been mistreated and misrepresented for decades. Gunn was born in Philadelphia in 1934 to a respectable middle-class family and a father in the military. He dropped out of high school but by the early 1970s he had become a celebrated writer, actor and director. After the box office success of William Crains’s 1972 blaxploitation film Blacula, Gunn was approached by the independent production company Kelly-Jordan Enterprises to make a black vampire movie. Gunn had recently made his feature film directorial debut with relationship drama Stop! for Warner Bros, though the studio shelved it and it remains unreleased to this day. Nicholas Forster, a Lecturer in African American Studies and Film & Media Studies at Yale University, who is currently writing a biography of Bill Gunn, emphasises Gunn’s professional stature at the time, pointing out that he was “one of the first five black directors hired by a major Hollywood studio and even though that movie doesn’t get released, he was at least somebody that Warner Brothers had taken a chance on. He had had success as a playwright at that point too – he sat on panels at the New York Film Festival and he was well recognised within that screenwriting world as a great writer and a really good actor.”

While the reasons for Stop! being consigned to purgatory are complex, Forster provides the further context that the 70s was “this very weird time. One of the reasons why Stop! was not released was that Warner Brothers went through three different ownership changes in the period of just a few years when Gunn was making it. Supposedly some paperwork has been lost and that makes it impossible for Warner Brothers to release the film, even though they have the print.” That there is a full Gunn-directed feature still sitting in a vault because of an administrative mix-up, despite the current interest in his oeuvre, is almost laughably absurd.

But while Warner Bros had failed to release his first film, his next one was born of a more independent spirit. Kelly-Jordan Enterprises was not one of the major studios: it was co-founded by Jack Jordan, a black American producer who had worked with Josephine Baker and considered Gunn “the black Stanley Kubrick”, and Quentin Kelly, an Irish-American producer. The two had worked with Maya Angelou on the 1972 film Georgia Georgia, for which she wrote the screenplay. So while the established narrative is that Gunn was tasked with artlessly making another Blacula by cash-hungry executives, Forster says “it seems reductive to say that they were just out for a cash grab”, while allowing for the fact “they’re producers, so what are they trying to do is have some sort of return on investment and this is the era of blaxploitation.”

Regardless of the intentions of the powers that be, Gunn wrote the screenplay and made the film in upstate New York, recruiting his actor friend Duane Jones to play the eponymous doctor. Jones had a single but significant screen credit to his name, having played hero Ben in George A Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), one of the most influential horror films of all time, made all the more radical by having a black actor at its centre. Forster explains that “at the time, Duane Jones had become a professor of French and he was like Gunn, very well read and kind of aristocratic. They both dressed very well and read philosophy and literature and loved music. They weren’t necessarily politically avant-garde in the typical sense, but they were both invested in aesthetics.” Marlene Clark, who had previously worked on Stop!, took the role of Ganja and his musician friend Sam Waymon (the brother of Nina Simone) played the Reverend Luther, Hess’s chauffeur and spiritual confidant, and wrote the score.

Bill Gunn on the set of his first film Stop! – which was set to be a major studio picture, but was shelved before release (Credit: Alamy)

Clarke’s role as Ganja is for Weston, the film’s most potent element. “In her autonomy, [Clark] is one of the major things that sets this film apart from its peers of the time. In the era of blaxploitation, black women don’t get the best representation, shall we say. Their roles can be quite stifling but her performance and her character is given so much richness. She’s such an alive figure, and that’s really rare.”

Watching Ganja & Hess is like listening to an expertly conducted orchestra. Gunn pulls from the distinct talents of each member of his ensemble and across arthouse, horror, blaxploitation and beyond to create a unique sensibility that is heart-stoppingly gorgeous. From the moment when Ganja and Hess marry, their union juxtaposed with symbols of Christianity and African spirituality, to the scene when Hess lovingly curses her with the same vampiric affliction that has transformed him, each frame radiates with meaning and is carefully composed like a Baroque oil painting. Amid the haziness of the 16mm cinematography, black skin lightly shimmers and crimson blood is preternaturally vivid. It’s sexy, confounding and deeply moving, and watching it, it seems to enter your bloodstream, moving gently through you and leaving you indelibly marked by all the beauty and despair Gunn sees in the world.

From rapture to derision

The film became the only US film selected for the 1973 Cannes Film Festival’s Critics Week and reportedly received a rapturous reception. While sincere enthusiasm is often hard to measure at a place like Cannes, where standing ovations are de rigueur, Forster says there was no denying that “Gunn was – as with many black artists of the mid-century like Richard Wright, Chester Himes or even James Baldwin to an extent – better recognised by a French audience than the predominantly white American audience. I do think that [the story of its reception] at Cannes might be somewhat exaggerated. But what exists now is French scholars and critics writing in French journals, celebrating the film or celebrating Gunn.”

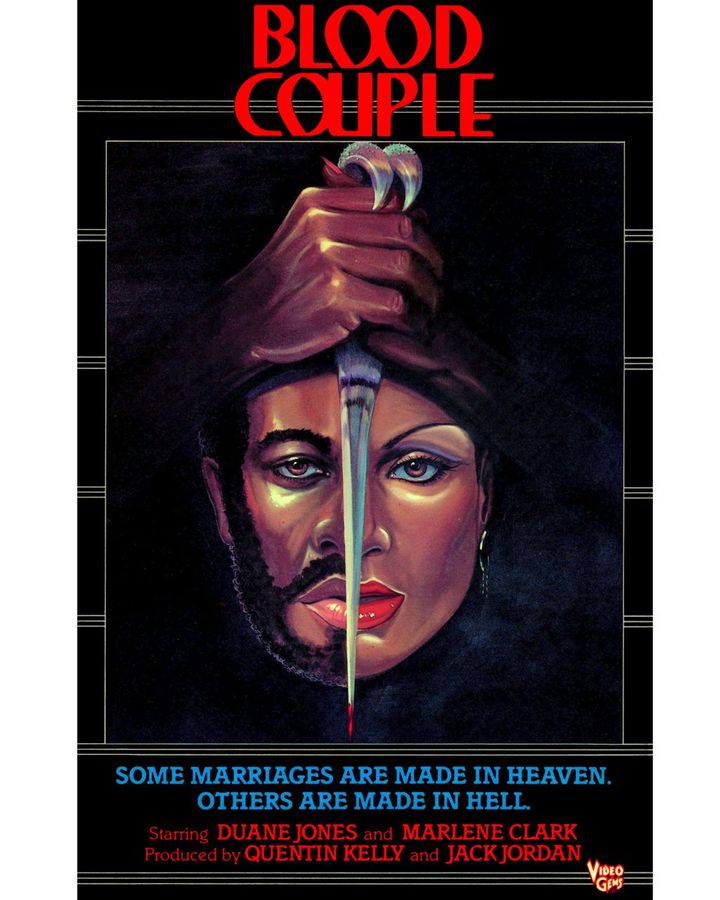

What is beyond doubt is just how poorly the film was then treated when it came back to the US. It premiered at New York’s Playboy Theatre and was derided by the critical establishment. Bad reviews led to bad box office and Kelly-Jordan Enterprises scrambled to recoup what they could, selling the rights to grindhouse company Heritage Pictures who put out a new version, substantially cutting it while including some additional footage and renaming it Blood Couple. Later, they labelled it with a whole host of titles including Black Evil, Black Vampire, Blackout: The Moment of Terror, Double Possession and Vampires of Harlem. Gunn wrote a damning indictment of his treatment in a now-famous open letter in The New York Times – the very paper that had described his film as “ineffectually arty”. Titled “To Be a Black Artist”, it is nearly as impressive a masterwork as the film itself.

It begins “THERE are times when the white critic must sit down and listen. If he cannot listen and learn, then he must not concern himself with black creativity.” He goes on to point out how little care the critics put into their reviews, fumbling major plot points. He points out that not one of them mentioned Cannes and took pride in their fellow American’s recognition abroad, but he reserves particular vitriol for the fact that Marlene Clark, “one of the most beautiful women and actresses I have ever known, was referred to as ‘a brown-skinned looker’ (New York Post). That kind of disrespect could not have been cultivated in 110 minutes. It must have taken at least a good 250 years.”

Gunn had his name removed from Blood Couple and the other butchered iterations of the film. A single print of Gunn’s original version of Ganja & Hess remained in existence; that was donated to New York’s Museum of Modern Art. With Gunn’s approval, it was screened there until its later restoration. In 2018, the distribution company Kino Lorber, The Museum and Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation collaborated to restore and remaster it in HD from a 35mm negative, making it more available for a wider reappraisal as a triumph by one of the great African-American artists. In the subsequent years, it has continued to be screened in rep and made available on multiple streaming platforms.

Ganja & Hess was re-cut and rereleased as Blood Couple after it was sold to the grindhouse company Heritage Pictures (Credit: Heritage Pictures)

Looking back at the reception to Ganja & Hess and Gunn himself, what is so striking is how confounding both he and the film were to critics. The New York Times itself labelled it a “confusingly vague mélange of symbolism, violence and sex”, and Forster explains that Gunn himself “was thought of as ‘difficult'” in a way he believes was “really just deeply anti-black”. The elegant and wealthy protagonist Dr Hess Green, and to a certain extent Gunn himself, lay far outside the mainstream culture’s limited view of black manhood and that was something of which Gunn was acutely aware. As Forster recalls, “Gunn has a line in his second published novel that ‘nothing is more confusing to a white man than a black aristocrat’. And he goes on to say, ‘white folks can understand an educated black man, but they cannot understand a sophisticated black man’.”

A critical renaissance

Duane Jones died in July 1988 and Bill Gunn the following April, before they could experience the cultural reappraisal and rerelease of their masterpiece. But while there is undeniably sadness in the fact they never got to bask in the glory of their film’s new audiences, to repackage him as a tragic figure that was simply of the wrong era is to do him a further disservice. As Brandon Harris wrote in Filmmaker magazine ahead of his 2010 BAM series The Groundbreaking Bill Gunn, “You could say that Bill Gunn was a man who came before his time, but that leaves you working under the flimsy assumption that a time more hospitable to this man of undeniable talents and mercurial preoccupations would someday come” asserting that he “was a man with a vision we were never quite ready for, black or white, studios or independents, 1970 or 2010”.

While no era may be fully equipped to appreciate the genius of Bill Gunn, fans of his vision have incrementally but steadily grown and Ganja & Hess’s status as a bona fide cult classic has been cemented over the past five years in particular. The restoration aside, Weston believes that is partly because over this period there have been “these conversations about representation and the relationship with black people in front of the camera and also behind the camera, particularly where it concerns horror cinema. And it was really interesting to have a resurgence of a film that daring and bold and ambitious. Around the same time [in 2017 and 2018], Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust was having a resurgence [too]. But Ganja and Hess had been on the rise long before that and it feels really precious that all of these things lined up for it to re-emerge in the way that it did.

One blip in its journey of reappraisal came from another black auteur, Spike Lee, who in 2014 remade Ganja & Hess as Da Sweet Blood of Jesus. While no one is denying Lee’s directorial prowess, it is, to put it mildly, not one of the stronger entries in his filmography. As Weston gently points out, “Bill Gunn is adept at subtlety, nuance, complexity, and allowing women the full depth of their own autonomy and independence. These are not things that I would argue are amongst Spike Lee’s many natural talents.” However Lee’s poor interpretation of the film may have in some ways contributed to the wave of renewed interest in the original.

Lee described the original as “one of my favourite films” and labelled Gunn as “one of the most underappreciated filmmakers of his time”. But while Ganja & Hess and Gunn were undeniably underappreciated, that is, in some respects, the least interesting thing about them.

For Forster, it’s important to recognise that while the story of Ganja & Hess and its reception is “powerful as a political tale about the exploitation of a black artist”, that narrative “can almost suck everything out of the richness and the vibrancy of a life that refused to be pinned down by any kind of categorical distinction that we would want to turn to”. He continues, “To me, when people say they wish Gunn had made more stuff, they are asking him to fulfil their needs in the present, rather than engaging with what he was actually looking to do or how he felt in his life.”

Spike Lee’s 2014 Ganja & Hess remake Da Sweet Blood of Jesus was poorly received (Credit: Alamy)

Most importantly it’s key to remember that Ganja & Hess, for all its glory, was not necessarily the apex and was certainly not the end of Gunn’s career. He continued living a life filled with uncompromised creativity. He spent much of his later years indulging his opulent tastes. Although Forster says that he doesn’t “totally understand how he was so financially okay”, Gunn lived in great comfort. “The house that he lived in in [the village of] Nyack [outside New York] was hundreds of years old and had been the house of [writer] Ben Hecht. It had a copper roof and had more than 23 rooms. It’s a very extravagant home.” He stayed closely bonded to Duane Jones and the filmmaker Kathleen Collins, and the trio would all die within a year of each other.

After Ganja & Hess, Gunn wrote the play Black Picture Show, about an ageing black screenwriter/playwright/poet who is near death and his director son. It is by Forster’s assessment “a complicated and difficult play” and was largely given an equally cold embrace as Ganja & Hess by both the white and black press. But Gunn was a man with vision, be it applied to a black vampire movie, experimental theatre productions, or novels, of which he published two. The spirit of Gunn was not one that would bend to the limits of the broader cultural imagination. To live a life and produce art that is so singular and uncompromised is ultimately more triumphant than tragic. For Forster, “it’s key to remember that Gunn was always dedicated first and foremost to an artist’s vision, his vision and he was able to pursue the life of an artist who would write 30-plus manuscripts over the course of his life.”

Forster has seen his upcoming biography’s subject steadily grow in recognition and popularity since he started writing it, but the surge in interest in Ganja & Hess and its creator is bittersweet. “He’s had a renaissance since I began this project and I’m glad that I’ve thankfully been some part of it. But I always clench my jaw a little bit when I hear him being put into those categories of like, ‘He’s a Black Arts Movement artist’. The reason I clench my jaw is they’re doing the same thing that hurt him in his life, which is putting him into a category that exists already, rather than reckoning with the fact that he was more than the challenges that he faced, and he broke so many of the categories that existed.”

So while Ganja & Hess’ journey from Philadelphia, to Cannes, to the archives of MoMA, to becoming a celebrated horror classic is a remarkable one, like Gunn, it is a work that defies easy classification. Engaging with this wholly unique film requires the viewer to challenge their preconceptions on vampires, class, colonialism and black artistry and even 50 years later, Gunn’s vision has lost none of its bite.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.