A chronicler of US turbulence

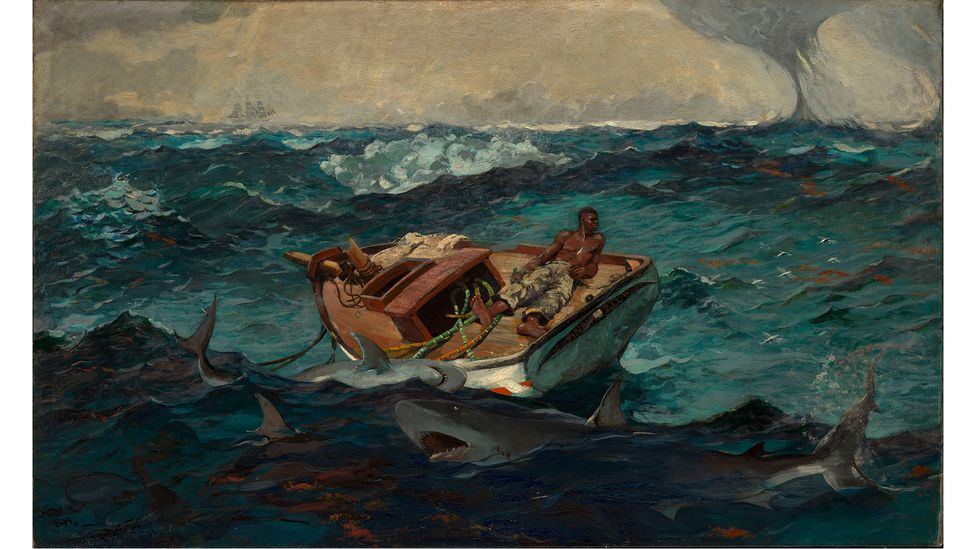

From the moment you enter the exhibition Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents, you are immediately at sea, caught up in the US artist’s 1906 masterpiece, The Gulf Stream. Against a swirling backdrop of storm-tossed waters and churning clouds, a lone black sailor lies propped against the edge of a small, battered boat. With his legs stretched before him, he turns his face to the side, away from both the damaged ship’s mast that has left him adrift, as well as from the open-mouthed sharks lurking in wait. He fixes his gaze with stoic determination on the dark, expansive waters filled with waves through which any number of fish fly and jump. But focused as he is in that direction, he cannot see the distant ghostly outline on the opposite horizon of a three-masted ship that just might offer the possibility of rescue.

More like this:

– The artist who likes to blow things up

– How fear shaped ancient mythology

– The women who redefined colour

“All of Homer’s themes come together” in this painting, says Stephanie L Herdrich, exhibition co-curator and associate curator of American Painting and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They include the struggle and conflict inherent in the natural world; the physical and emotional trauma of the US Civil War; the inequities of race and slavery left unresolved by that war; the thoughtless devastation of nature, whether due to battle or predatory hunting; and the US imperialist ambitions in the aftermath of the Spanish-Cuban-American War. It’s not the survival of the fittest that Homer dramatises, but the resilience that life requires to endure and withstand the struggles we meet. Taken together, these themes provide not just a subtext but a fuller context for a deeper understanding of his work.

The struggle for survival captured in The Gulf Stream is on one level obvious. But the deeper conflicts hinted at within the painting make it a touchstone of Homer’s art, and emblematic of US history and culture.

The Met’s exhibition guide says that The Gulf Stream is ‘an allegory of human endurance amid the forces of nature’ (Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

To begin with, in this painting, as in so much of his work, Homer depicts a story in medias res – a literal drama of life and death, rescue or wreckage – that is still unfolding but remains as yet unresolved. These unknowns yield palpable tension, filling the canvas with suspense and ambiguity. Among the questions to be answered: who is the sailor, where does he come from, and what is his destination (not to mention, his destiny)?

Homer has provided a variety of suggestive clues, starting with the origins of the boat, whose name and home port, “Anna-Key West”, are painted across its perilously tilting rear. As for its cargo, one of the sailor’s bare feet lies atop an entangled set of colourful sugarcane stalks – a reminder of the commerce across the Atlantic Ocean that was at the heart of the slave trade, and whose legacy remained alive then, and continues now.

By titling his painting The Gulf Stream, Homer brought still another dimension to this cross-Atlantic entanglement. The Gulf Stream is a natural phenomenon that affects the ecology and climate on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Homer was well aware of its geographical course, having read works of oceanography, and himself having travelled along its route. Starting at its source in the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf Stream’s warm currents track the coast of US southern states before branching off at the tip of Florida towards the islands of Cuba, the West Indies, and Bermuda. From there, the stream travels swiftly up the North American Eastern Seaboard all the way to the northern edge of Canada before turning east across the Atlantic Ocean towards Northwest Europe, the British Isles and Scandinavia.

Winds of change

These currents are responsible for the accelerating wind velocity that carries ships more quickly from North America to Europe. But they can also contribute to destructive, high-speed hurricanes, like the one depicted in this painting, and the powerful storms that increasingly plague these same environments in our own time of climate change. No wonder that, gazing at Homer’s The Gulf Stream, it’s natural to wonder what will be the fate of this protagonist, caught in this storm’s seemingly unyielding crosscurrents? What are the metaphorical crosscurrents beyond the Gulf Stream that we confront in our lives today?

The exhibition – which comprises 88 oil paintings and watercolours – remains on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art until 31 July. A slightly smaller version will then transfer to London’s National Gallery in September with the title, Winslow Homer: Force of Nature.

National Gallery’s director Gabriele Finaldi says that Homer explored ‘the struggle for survival and personal isolation’ – as in The Life Line (Credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art)

This will be the first in-depth survey of Homer’s work to appear in the UK, but the show is a revelation, whatever the viewer’s familiarity with his work. Homer’s eye for the dramatic detail makes each work of his into a story, which the viewer enters into with empathy and emotion. His scenes of the US Civil War (1861-1865) make more than real the legacy of conflict, both in terms of the human cost and the wastage of nature. His seascapes feature the ports, villages and communities of Maine as well as of England and the Bahamas – all places that harbour nature’s breathtaking beauty as well as its attendant, sometimes fatal, risks and wrecks, which only heroic, gasp-producing rescues can help avert.

It’s impossible not to be struck by the crosscurrents of slavery and freedom on display in the works here, related to the Civil War and its aftermath. By the time war broke out, Homer, who was born in Boston, had moved to New York City where he had begun a career as a freelance illustrator for Harper’s Weekly and other magazines. Embedded with Union troops, he visited the front three times. As he marched with the men, he documented the daily routines of camp life alongside battle manoeuvres and bloody skirmishes, kept watch with soldiers serving on the pocket lines, and observed surgeons and medics trying to save the wounded.

The stark images of the conflict took hold of his imagination and made their way into his art. His first oil painting, The Sharpshooter (1863), captures with chilling, anonymous intimacy of the work of a uniformed marksman as he perches on a pine-tree branch for camouflage, even as he squints into the viewfinder to find his target and puts his finger to the rifle trigger. But his immersion in the daily life of war also took an emotional toll. Homer compared the sharpshooter’s job as being “as near murder as anything I ever could think of in connection with the army”. Upon his return from his sojourns at the front, his mother wrote in a letter, “He came home so changed that his best friends did not know him.”

In works like The Veteran in a New Field, Homer chronicled some of the most turbulent and transformative decades of US history (Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Still, when the war ended, Homer embraced hopes of national reconciliation, emotions embodied in the painting The Veteran in a New Field (1865), says co-curator Herdrich. “The veteran has cast aside his uniform,” which is visible in the lower right corner, and exchanged the battlefield for a field of grain – a scene that evokes the passage from Isaiah, “They shall beat their swords into plowshares”. But there is ambiguity, too, with the soldier-turned-farmer’s single-bladed scythe also a reminder of the Grim Reaper’s vast death toll over the course of the war.

There is also uncertainty and ambiguity present in such paintings as A Visit from the Old Mistress (1876) – which depicts a family of four black women engaged in a testy conversation with a white woman, dressed in sombre widow’s weeds, who had once enslaved them. Equally haunting is The Cotton Pickers (1876), a scene from the post-slavery economy of the South featuring two young black women rendered with exquisite sensitivity and empathy as they go about their labour in the fields.

These renderings are the opposite of the caricatures of black people typically produced at the time, says William R Cross, author of the comprehensive biography, Winslow Homer: American Passage. “Throughout his life, Homer had a deep heart for the figures who were often forgotten and neglected,” extending beyond black Americans to indigenous groups as well as the poor and disadvantaged.

Through paintings like A Visit from the Old Mistress, Homer depicted black people in a more nuanced way than other artists of the era (Credit: Smithsonian American Museum of Art)

From the 1870s onward, Homer increasingly focused on themes of nature, especially in the course of his visits and travels to the coastal regions of Maine, Massachusetts, the Caribbean, Bermuda, Florida and England, where he spent time at the coastal village of Cullercoats. Increasingly, in these works, he delved into the subject of the unpredictability of life and struggles for survival. Dramatic scenes of heroic rescue from the water, such as The Life Line (1884) and Undertow (1886), underscore the precarious balance between life and death, between deliverance from danger and falling prey to the elements of nature.

Homer’s paintings also explored the imperialist ambitions of the US, such as with Searchlight on Harbor Entrance, Santiago de Cuba (Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

And even decades after the Civil War, the dangers of other wars resonate in Homer’s work, especially in Searchlight on Harbor Entrance, Santiago de Cuba (1901) painted in the wake of the Spanish-American War of 1898. The painting’s sense of foreboding derives from the eerie darkness that surrounds the monumental Spanish-built fortress and long mortar canon that dominate the canvas. The searchlight casting its light on the harbour is neither Spanish nor Cuban, though; it belonged to the US Navy. Cuba itself seems of less importance in this image than the two powers of the US and Spain that are warring over it.

Perhaps it was no accident that Homer suggested to his art dealer that this painting might pair well with The Gulf Stream. Both paintings are linked by the sugarcane trade between Cuba and the United States. Sugarcane is the cargo carried in The Gulf Stream’s battered ship. America’s victory in the Spanish-American War served to ensure smooth sailing for American business – regardless of how wildly the winds blew.

A dangerous passage

And always at the centre of this exhibition, both physically and metaphorically, is The Gulf Stream. At the Metropolitan Museum exhibition, viewers first glimpse the canvas, which dates to the end of his career, hanging on the wall of another gallery in the distance. That glimpse stays with you as you move forward from gallery to gallery, through evocative scenes of Civil War soldiers, and then the fraught aftermath of slavery. You arrive at Homer’s sunny seascapes of the Caribbean and then feel thrashed all the more by the life-threatening storm waves that assert themselves in other works set in communities on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and along the course of the Gulf Stream itself.

This, then, is the passage traversed by the black sailor in The Gulf Stream. For Cross, this figure is a kind of Everyman who is both American and black. Homer “put his Everyman in a position in which the outcome is quite uncertain”, Cross comments. “There is great hope – evidenced by the fact that he is looking to the flying fish – and also the presence of the ship which I find rather ghostly. It would seem in some ways like a part of a dream rather than a real ship. There’s no hiding the threat that comes from the storm or from the sharks. And yet this Everyman does not appear to me to have given up hope. He is poised with a sense of honesty about the circumstances, and is also intent on his own survival.”

As a painting, says Cross, The Gulf Stream “should be regarded in the same context as Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and other great works of art and literature.” But as a physical force of nature, the Gulf Stream also carried additional significance for Homer. “I think that ultimately Homer believed in an order which he saw in the Gulf Stream,” Cross says. “It was a system, and unlike the evil system of slavery, the Gulf Stream was a natural system that brought with it both danger and beauty.” In this exhibition, all those aspects are on display.

Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 31 July; Winslow Homer: Force of Nature is at the National Gallery, London, from 22 September until 8 January 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.