The Slavic witch that still fascinates

In fairy tales, women of a certain age usually take one of two roles: the wicked witch or the evil stepmother, and sometimes both.

More like this:

– The horror that demonised older women

– The brutal new female icons in film and TV

– The silent horror that still terrifies, 100 years on

A key figure from Slavic folklore, Baba Yaga certainly fulfils the requirements of the wicked witch – she lives in a house that walks through the forest on chicken legs, and sometimes flies around in a giant mortar and pestle. She usually appears as a hag or crone, and she is known in most witch-like fashion to feast upon children.

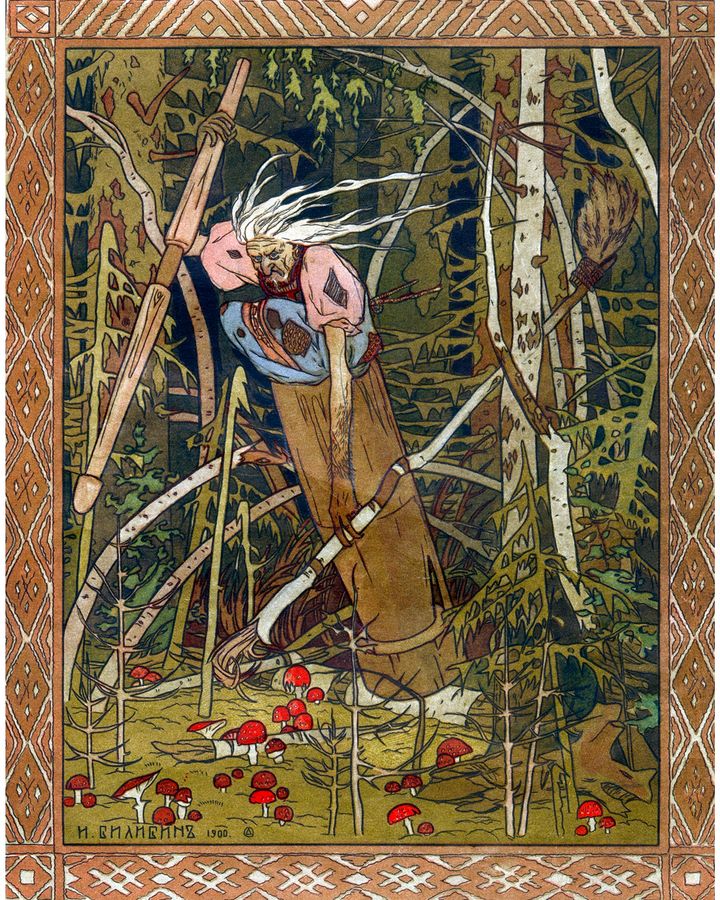

As demonstrated in the Russian fairy tale Vasilisa the Beautiful (depicted above in a 19th-Century illustration), Baba Yaga can be both hero and villain (Credit: Getty Images)

However, she is also a far more complex character than that synopsis suggests. Cunning, clever, helpful as much as a hindrance, she could indeed be the most feminist character in folklore.

So enduring is the legend of Baba Yaga that a new anthology of short stories, Into the Forest (Black Spot Books), has just been released, featuring 23 interpretations of the character, all by leading women horror writers. The stories span centuries, with Sara Tantlinger’s Of Moonlight and Moss offering a dream-like evocation of one of the classic Baba Yaga stories, Vasilisa the Beautiful, while Carina Bissett’s Water Like Broken Glass sets Baba Yaga against the backdrop of World War Two. Meanwhile Stork Bites by EV Knight ramps up the horrific aspects of the myth as a salutary tale for inquisitive children.

The history of Yaga

Baba Yaga appears in many Slavic and especially Russian folk tales, with the earliest recorded written mention of her coming in 1755, as part of a discourse on Slavic folk figures in Mikhail V Lomonosov’s book Russian Grammar. Before that, she had appeared in woodcut art at least from the 17th Century, and then made regular appearances in books of Russian fairy tales and folklore.

If you’re a film fan, you might recognise the name from the John Wick films starring Keanu Reeves, in which the eponymous anti-hero is called Baba Yaga by his enemies, giving him the mysterious allure of an almost mythical bogeyman. Japanese animation legend Hayao Miyazaki used Baba Yaga as the basis for the bathhouse proprietor in his award-winning 2001 movie Spirited Away. Baba Yaga appears in music, too; Modest Mussorgsky’s 1874 suite Pictures at an Exhibition features a ninth movement called The Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba Yaga). She might well be making an appearance on the small screen soon, as well; Neil Gaiman used her in his Sandman comics for DC, the adaptation of which has just had its second season announced by Netflix.

Gaiman also used Baba Yaga in The Books of Magic comic series, and the way he has deployed the character highlights her moral ambiguity: where she was helpful in Sandman, she is more of a baddie in Books of Magic. He tells BBC Culture he first encountered Baba Yaga aged six or seven when he read children’s fantasy book The Dragon’s Sister and Timothy Travels by British writer Margaret Storey, in which she appeared. “[I] felt she was the most interesting of all the witches, and felt that way even more when I read some of the Russian stories in which she appears,” he says. “She seems to have her own life outside of the story, which so few fairy tale characters do.”

Into the Forest is edited by Lindy Ryan, a writer and full-time professor of data science and visual analytics at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey who is also the founder of Into the Forest’s publisher Black Spot Books, a small press dedicated to female horror writers. So how did an American end up fascinated by this Slavic myth?

“My Russian stepmother emigrated to the United States shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union,” says Ryan, “and along with my stepsister and step-babushka, she brought borscht, matryoshka dolls, and Baba Yaga. While most girls my age were growing up with nicely sanitised Disney version princesses, I preferred the stories by Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, and Hans Christian Andersen – and, of course, in the books of Slavic fairytale and folklore that talked of Baba Yaga.”

Baba Yaga has been an inspiration for animation legend Hayao Miyazaki, including with the character of the bathhouse proprietor in Spirited Away (Credit: Alamy)

In fact, the origins of Baba Yaga might go back far further than the 17th Century — there’s a school of scholarly thought that says she’s a Slavic analogue of the Greek deity Persephone, goddess of spring and nature. She’s certainly associated with the woods and forests, and the wildness of nature. “The essence of Baba Yaga exists in many cultures and many stories, and symbolises the unpredictable and untameable nature of the female spirit, of Mother Earth, and the relationship of women to the wild,” says Ryan.

What lifts Baba Yaga above the usual two-dimensional witches of folklore is her duality, sometimes as an almost-heroine, sometimes as a villain, and her rich, earthy evocation of womanhood. “Baba Yaga still remains one of the most ambiguous, cunning, and clever women of folklore,” says Ryan. “[She] commands fear and respect, and simultaneously awe and desire. I admire her carelessness and her independence, even her cruelty, and in a world where women are so often reduced to hazy blurs of inconsequence, she is a figure that reminds us that we are ferocious and untameable, and that such freedoms often come at a cost.”

In fact, she’s something of a proto-feminist icon. “Absolutely she is,” says Yi Izzy Yu, one of the authors who has contributed a story to Into the Forest. One of the ways in which she merits such a description is that she completely upends the nurturing mother stereotype applied to women by eating children rather than pushing them out or breastfeeding them. “She’s powerful despite not being attractive in a conventional sense. She lives by her own magical terms rather than mundane rules,” says Izzy. “And she challenges conceptual categories at every turn. Even her home is both house and chicken, making her, yes, housebound in a sense, but not in any way ‘tied down’. In this [way], I guess, she is an early motorhome gypsy.”

A true outlaw

Izzy likens Baba Yaga to trickster characters from many mythologies, such as Norse god of mischief Loki or Coyote from Native American folklore. “While Baba Yaga often plays a villain, she is also likely to offer assistance. For example, in Vasilisa the Beautiful, she helps free Vasilisa from the clutches of her evil stepfamily,” she says. “And while Baba’s dangerous to deal with, like many of those who operate on the shadowy side of the law in contemporary movies, she can as well prove herself invaluable in dangerous circumstances.

“In this way, Baba Yaga complicates the passive female nurturing role with a type of ‘I’ll do whatever the heck I want’ outlaw power that you ordinarily only see associated with men. You could say then that Baba Yaga crosses the wicked witch trope with the fairy godmother trope to create an ultimately far more unpredictable and powerful role than either of those.”

Izzy was born and grew up in Northern China, and as a great deal of Russian literature was translated into Chinese, Baba Yaga crossed the border and into the Chinese psyche. “My first exposure to Baba Yaga was a Chinese cartoon I saw when I was very young. I remember this cartoon because I told my grandmother that Baba Yaga looked exactly like my Big Uncle. This made her laugh. Big Uncle did not laugh,” says Izzy.

The John Wick films are some of the unlikelier cultural works to reference Baba Yaga, as the name given to Keanu Reeves’ anti-hero by his enemies (Credit: Alamy)

The trope of the mountain or forest crone or witch is a popular one across East Asia, mainly because, says Izzy, “the mountains are associated with great spiritual power and with hermit figures who decide to live life on their own terms – much like how Baba Yaga is very much her own woman”. She adds that in Japan there’s a character called Yamamba who is “strikingly similar to Baba Yaga – she too is often portrayed as having repulsive physical features and a taste for children. She is also morally ambiguous, alternately described as a monster cannibal or an agent of change and transformation, and a guardian of heroes”.

For Lindy Ryan, the concept of a women-centric horror anthology came before the idea of a Baba Yaga-themed book… but the great witch of the forest exerted her influence. “I wanted the anthology to feature the voices of women around the world who were unafraid to tell their stories, to tap into their own wildness and wickedness, and in that way I feel like Baba Yaga came to me as a muse for the anthology,” she explains. “What was perhaps most surprising was the readiness with which contributors took to the task, and the resonance that Baba carries across the world. She truly is a universal character, and I was amazed at the responses from women around the world who united their voices with hers.”

Izzy’s contribution, The Story of a House, explores one of the unique facets of the Baba Yaga myth – her ramshackle cottage that walks on chicken legs, recounting its creation and construction. “I was just charmed thinking of the little chicken legs of this big old house. This directly led me to wanting to write something about the house. As well, I had just come off translating The Shadow Book of Ji Yun – a collection of 18th-Century Chinese weird tales. It’s filled with fox spirits, Tibetan Red-Hat black magic, and other flavours of shamanism, as well as stories of preternaturally intelligent or empowered animals and weird metamorphoses. This inspired the atmosphere I wanted to create in The Story of a House and its themes.”

Does the legend of Baba Yaga have any lessons for us today? Izzy thinks so. “She’s a shamanic trickster, a category and boundary-crosser, a [reminder] that freedom lies a little beyond the border of social norms, and that we can learn as much from the dark as the light. Ultimately, I think she teaches ‘Both/And’ logic. She reminds us that we are both hero and villain, that a chicken can also be a house, and that we can embrace both the desires of the flesh and the secrets of the spirit.”

Ryan agrees, and has a salutary warning for those who would dismiss the power of Baba Yaga, and in doing so, women everywhere. “I think we’d do best to remember that Baba Yaga may hide herself in the woods, but she is watching and she is remembering,” she says.

Into the Forest: Tales of the Baba Yaga, edited by Lindy Ryan, is out now from Black Spot Books.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.