The most shocking film ever made?

But there was a faction beneath the umbrella of J-horror – a term that perhaps better describes the influx of evocative Japanese films in the West during that period rather than a uniform style or genre – that arguably left an even greater impact than these more traditional horror films, like Ring and Dark Water. Whereas these titles favoured subtle psychological tension, drawing upon Noh and Kabuki theatre and Japanese folk mythologies for their visuals and themes, films like the aforementioned Audition, Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale (2000) and Sion Sono’s Suicide Circle (2001) did away with long-haired ghosts and subtle psychological tension, instead emphasising ultra-violent set-pieces and taboo subject matter such as torture, child murder and mass suicide. “They were something we’d never seen before,” Adam Torel, managing director of the UK’s leading Japanese film distribution label, Third Window Films, tells BBC Culture. However he asserts that one film in particular led the field with the boundaries it dared to push.

‘Garish and perverse’

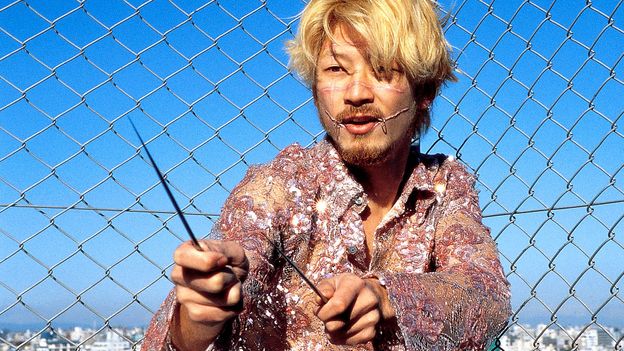

Ultra-violent and provocative, Ichi the Killer lays out its super-charged film language in just a few delirious moments. Chaotic, jerking camera motions and a hyper-kinetic editing style transform Tokyo’s Shinjuku district into a neon blur as the film opens, as the bustling drums and industrial guitar sounds of Karera Musication (a side project of avant-garde noise-rock band Boredoms) provide a disorientating soundtrack. Soon after, the fate of the missing yakuza boss Anjo is confirmed to the audience with a cut to a room covered in CGI blood and cow intestines – and the film’s intense visual identity is made plain.

“It comes straight from V-Cinema,” Chika Kinoshita, a professor of Film Studies at Kyoto University, tells BBC Culture, of the low-budget film’s frenetic filmmaking style. She refers to the thriving straight-to-video market that emerged in Japan in the late 1980s, just as the economic bubble burst; a new arena that opened up avenues for young directors like Miike, Nakata and Kurosawa to prove their worth. Having established themselves in a field that emphasised cheap thrills good for eye-catching VHS box covers, these filmmakers would graduate to the big screen at almost exactly the same time that Japan had landed its historic triple-win at the world’s leading film festivals.

While Miike shared the benefits of these industry changes with many of the emerging J-horror directors, Ichi the Killer drew its aesthetic influences from elsewhere. Traditionally, “J-horror is much more muted and atmospheric,” Kinoshita explains, and indeed, the parallels between films like Ring and Ju-on: The Grudge with classic Japanese horror texts such as Kuroneko (Kaneto Shindo, 1968) and Kwaidan (Masaki Kobayashi, 1965) are evident. Ichi the Killer instead had a closer affinity with the brutal and energetic gangster thrillers of the 1970s, such as Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honour or Humanity series, says Kinoshita. These films were marked by violent acts filmed on handheld cameras, set in the chaotic black markets of post-war Hiroshima in what was an economic crisis that, in many ways, anticipated that of the ’90s. Indeed, Fukasaku’s cult classic Battle Royale – an ultra-violent Lord of the Flies about a class of children instructed to fight to the death – cemented his own position as a central part of the “Asia Extreme” revolution. Miike would acknowledge his debt to the master explicitly a year after Ichi the Killer’s release, when he remade Fukasaku’s 1975 gangster classic Graveyard of Honour.