The ‘scandalous’ life of Ethel Smyth

She was a force of nature, a feminist composer of phenomenal talents, whose music set records and won great acclaim. She had passionate affairs with prominent women – including the celebrated suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst – and a married man, and a lasting friendship with Virginia Woolf. Her unstoppable spirit shocked polite society, her bigotry offended, her activism landed her in prison. She has been a figure of fun as well as adulation, and viewed as both problematic and brilliant.

More like this:

– The black composer erased from history

– Inside Kate Bush’s alternate universe

– How the first pop star blazed a trail

Ethel Smyth was one of the early-20th Century’s most original and controversial voices in classical music and social politics. Composer, conductor, author and suffragette, Smyth was famed for her operas and vibrant character. All her life she continued to fight to be heard and have her music performed in the face of misogyny and male critics who would dismiss her as a “lady composer”. Her defiant riposte was to write “masculine” music and wear manly tweed suits.

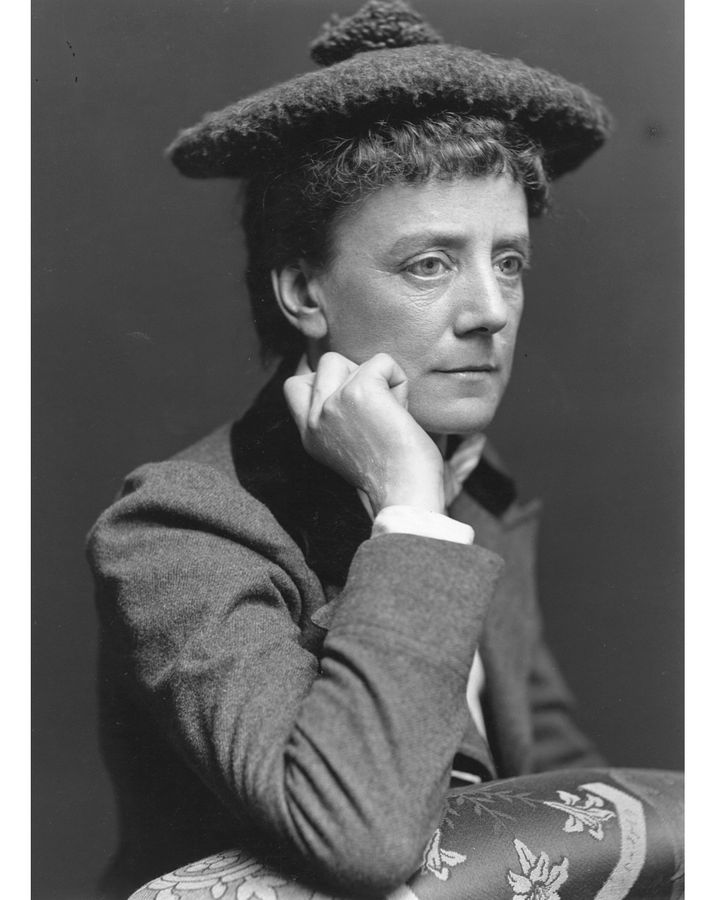

Ethel Smyth, photographed circa 1901 – from childhood onwards she was defiantly unconventional (Credit: Getty Images)

After Smyth’s death towards the end of World War Two, her music all but died with her. But in recent years, there’s been a revival of her work, and interest in her unstoppable personality. There have been performances in 2018 of Smyth’s rousing suffragette anthem, The March of the Women – to mark the centenary of many women winning the right to vote – and a Grammy-award-winning recording of her 1930 opera The Prison. And crowning it all, her most impressive work, the opera The Wreckers, opened the prestigious Glyndebourne festival in May, to glowing reviews for, as the Times said, its “wild waves of passion”. The opera will also be performed at this summer’s Proms, with other of her compositions. Smyth is back in the limelight, just as she would have loved it.

Smyth was a disruptor and a rebel from a young age. Born in Kent in 1858 into an upper-middle class family, she railed against the restrictions of her Victorian-era girlhood. Her father was a major general in the Royal Artillery, and strongly opposed her desire to study music – so she locked herself in her room and refused to eat or leave it until he capitulated. Having got her way, she went on to study at Leipzig Conservatory, in Germany; there she met Tchaikovsky, Dvořák and Grieg, and through a tutor was introduced to Brahms and Clara Schumann. Smyth began confronting the gender bias that would relegate her to performer-teacher instead of her career vision – a composer of full-scale works.

Dr Amy Zigler, assistant professor of music at Salem College, has presented research on Smyth since 2005. “The obvious answer is her gender,” she says, in response to why Smyth might have been under-appreciated. “In reviews of her music from the 1880s, 90s and early 1900s, at a time when she was building her career, there is almost always a comment about her gender.” It was not only Smyth who suffered discrimination: “For more than a century, the gatekeepers believed women weren’t capable of writing music on a par with male composers.”. If Smyth and others wrote music that was “energetic, loud, forceful or ‘virile'” it was damned as “unnatural and unbecoming of a woman” says Zigler. If they wrote music that was “graceful, soft, lyrical or sentimental, it was deemed to be just ‘parlour’ music for young women to play at home – unimportant or inferior.”

While fighting sexist attitudes, Smyth won the support of conductors like Sir Thomas Beecham and patrons, to the extent that “almost everything she composed was performed” says Zigler. “She pursued her passions, in her music and personal life. She was ambitious and unapologetic. She didn’t seem afraid to knock on a conductor’s door or smash in a politician’s window – both were the necessary course of action her mind.”

A production of Smyth’s opera The Wreckers opened 2022’s Glyndebourne festival to great acclaim (Credit: Richard Hubert Smith)

Writings by feminist musicologists like Sophie Fuller and Elizabeth Wood have helped drive interest in Smyth’s and other women’s music, says Zigler, whose website ethelsmyth.org is a wellspring on the composer. For those exploring her work afresh, she suggests the chamber pieces, songs, and huge choral and orchestral works: Smyth’s Sonata for Violin and Piano, Op 7 from 1887; the Kyrie from her Mass in D (1891), On the Cliffs of Cornwall from The Wreckers (1906); Possession for voice and piano, 1913; and the opening of The Prison (1930).

The latter, a choral symphony, was conceived by Smyth and Brewster as a philosophical dialogue between a prisoner and his soul. It was her final major work, and its first performance in Edinburgh, February 1930, with Smyth conducting, was acclaimed – but it would be nine decades before it was recorded. When it was, in 2020, by Chandos (a record company noted for reviving hidden gems), Zigler attended at the invitation of conductor James Blachly.

“I think The Prison winning the Grammy in 2021 definitely drew attention to Smyth,” she says, but she feels interest surged in 2018 when various organisations were performing March of the Women, and looking at what else Smyth composed.

Dr Leah Broad agrees Smyth faced “an awful lot of obstacles in her life because of gender”. She is writing a radical feminist history of four women “trailblazers” (out in the spring of 2023); Smyth is one of the four, with other composers Rebecca Clarke, Dorothy Howell and Doreen Carwithen. “I love them all,” muses Broad but feels Smyth “is probably the one I would most loved to have met – provided we didn’t talk about politics.”

Smyth is a pioneer of modern opera and, though her work was forgotten for decades, it is now enjoying a revival (Credit: Richard Hubert Smith)

Broad tells BBC Culture that Smyth “had some very strong political views that she liked to hold court about… She was a staunch conservative, and held a number of opinions that, while popular in her day, are less so now.” Broad told the Guardian that Smyth was “very much a woman of her time, in that she held problematic views about race, and subscribed to the then-popular belief in white English superiority.” She may also have “inadvertently made life harder for female musicians coming after her. Smyth certainly forced many of her critics to confront their own gender prejudices, but she did little to actively uplift or support other female composers.” Still, Broad found her “the most fun to write about”. She enjoyed the story of an interviewer who went to meet Smyth to find she had tied herself to a tree: “She explained it was to help improve her posture as a conductor… she didn’t have a sense of self-awareness like many other people.”

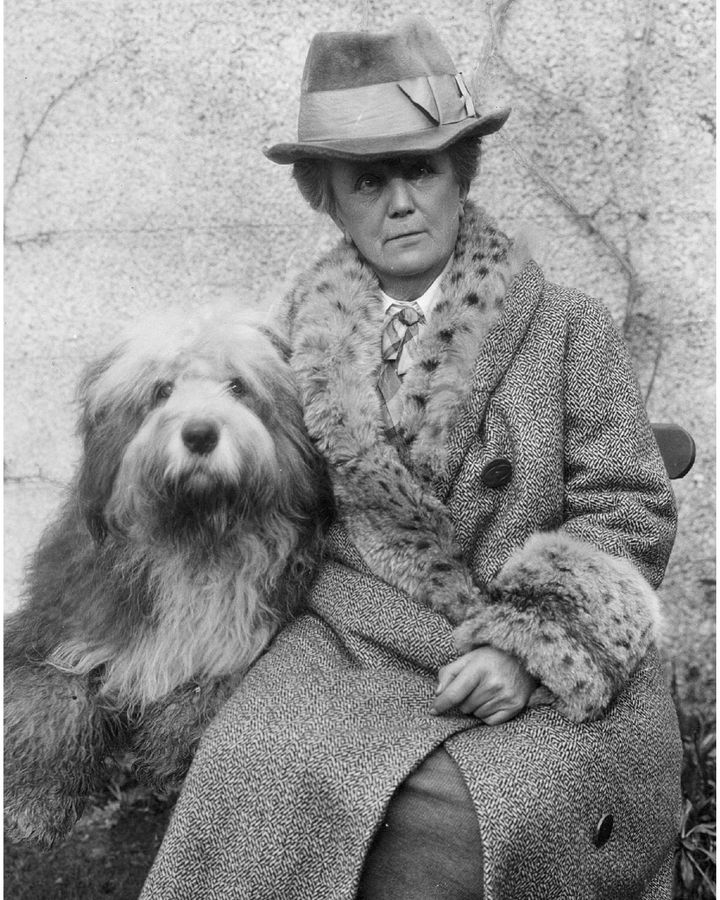

Smyth’s vitality found an outlet in sport as a young girl, and in adulthood she loved mountaineering, tennis, long country walks and a round of golf. She was nearly always accompanied by a pet dog. She could arrive unannounced, expecting to be entertained, as she is said to have done once to Virginia Woolf, who was in bed in her pyjamas. Her rambunctious persona, ripe for parody, was a model for EF Benson’s Dodo novels (1893-1921) about a frivolous society figure, and also inspired Dame Hilda Tablet, in comedy radio plays by Henry Reed in the 1950s.

And then there was her much-discussed sexuality. There was a long list of lovers, including Pauline Trevelyan, Lady Mary Ponsonby, Violet Gordon-Woodhouse, Winnaretta Singer, the Empress Eugenie and Pankhurst. Her only male lover is said to have been Henry Brewster, a philosopher friend and the librettist of some of her operas. She had an intense bond with Brewster lasting decades, and affairs with his wife, Julia, and sister-in-law, Edith Somerville. In 1892, Smyth wrote to Henry: “I wonder why it is so much easier for me to love my own sex more passionately than yours. I can’t make it out, for I am a very healthy-minded person.”

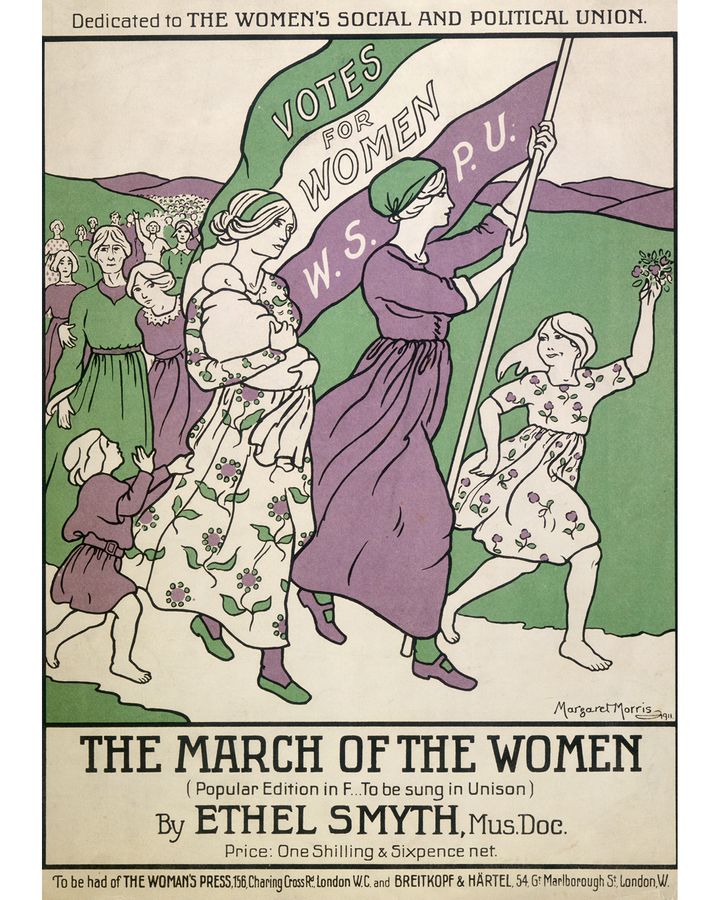

The song sheet of The March of Women, written by Smyth in 1911, and dedicated to suffragette campaigner Emmeline Pankhurst (Credit: Getty Images)

“Smyth was defiantly queer,” writes Professor Sophie Fuller, lecturer in music at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, in a post on Glyndebourne’s website “[and] as open as anyone of her generation could be about the intense, and sometimes sexual, relationships with women that drove so much of her often-turbulent life.”

“She goes through phases of being obsessed with a woman, they’ll have a passionate relationship for a few years, then it will become a friendship,” says Broad. Brewster is “the anomaly. Her sexuality is complex – she herself said she was in a constant process of working it out. What is most exciting is she does not fit into any boxes.”

Melly Still, director of the Glyndebourne production of The Wreckers, studied Smyth’s writings as research. “Henry Brewster was the only man [Ethel] slept with and felt closest to – but she never wanted to marry him, though he did ask her when his wife died. She never wanted to lose her independence. She was more religious and conservative until she met him. He supported her passions, and encouraged her to form relationships.”

Defiant and unorthodox

No relationship dimmed her drive for composing music, however, and at the fin-de-siecle she built her repertoire. The Wreckers – her 1903 masterpiece about a god-fearing community in Cornwall who live off shipwrecks – then broke ground when Smyth became the first woman to have an opera staged at the New York Metropolitan Opera.

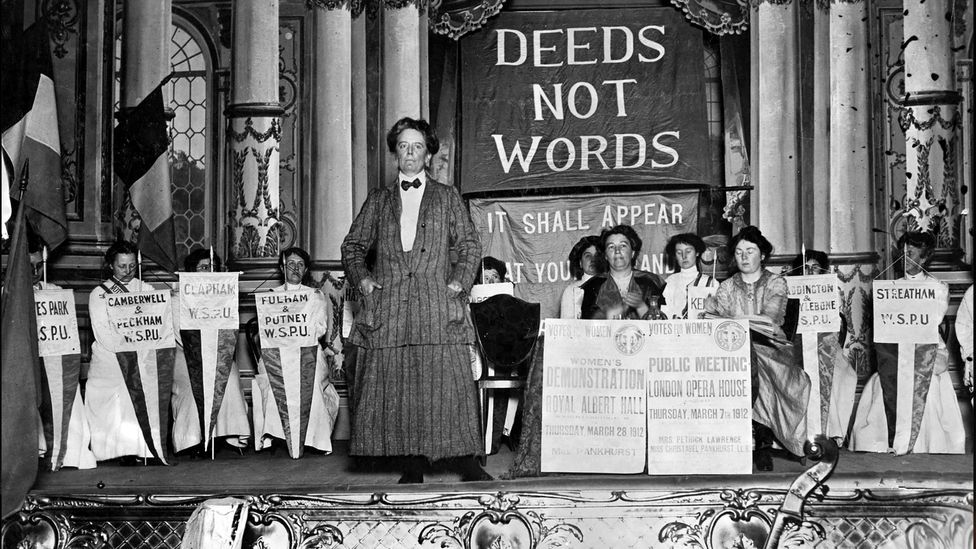

Smyth, pictured here at a 1912 meeting, was a prominent member of the women’s suffrage movement – but she held bigoted views about race (Credit: Alamy)

Melly Still believes The Wreckers reflects the defiant, unorthodox views of its creator: “The [Cornwall] community is really a symbol of an isolated Britain… because she was bisexual and as lovers, he was married. They were trying to manage their worlds at the start of the 20th Century. In a society that was frowning on everything they did… they felt that there was something quite insular about Britain at the time.”

Still describes The Wreckers as a “feminist opera” and says: “It’s about the women in it finding their voice. Its central character, Thurza, tries to break free from the restricted world she is forced to live in. And Smyth subverts all the operatic tropes. She made the moral heart of the opera a mezzo, a voice type normally consigned to the witches/bitches/breeches roles; and the soprano, Avis, is a really feisty character – not the classic transgressor saved by a Prince Charming.”

Musically, too, the opera was innovative for its time. Zigler tells BBC Culture: “What makes The Wreckers so fascinating for me is the drama inherent in the music. Whether it’s the love duet between Thurza and Mark in Act II, or the kangaroo court in Act III, Smyth creates tension through her melodic style and harmonic language, which, coupled with the orchestration, leaves the audience wondering what’s going to happen next. At the heart of the score, too, is the French libretto; Smyth and Brewster collaborated on the opera, and she drew inspiration in part from the French text he created – not only what the words were saying but how they sounded, their rhythm and inflection. All of this combined creates an opera that is exciting.”

Glyndebourne’s production of The Wreckers has attracted praise and glowing reviews. The Observer noted that director Melly Still and conductor Robin Ticciati “have done Ethel Smyth’s 1906 opera proud, with dynamic and intense performances and an excellent cast and chorus”. Meanwhile the Financial Times said “the sheer dramatic force is something to behold”, adding “there is no English opera written before or after The Wreckers that can match Smyth’s open-hearted, unapologetic, no-holds-barred passion.”

The Wreckers has been described as a feminist opera that is also about British insularity (Credit: Richard Hubert Smith)

Smyth won huge popularity in the 1920s, which no doubt led to her being made a dame in 1922, and becoming the first woman to be given a damehood for her contributions to music and publication. In another first, she was the first woman composer to have an opera staged at Glyndebourne. Broad points out, “We’ve still got a way to go before a woman’s name on the concert programme is unexceptional” adding that only 8.2 per cent of orchestral concerts worldwide in the 2019-20 season contained music by women, – “not much better than the Proms were managing in 1940”.

When Stephen Langridge took the role of artistic director at Glyndebourne in spring 2019, The Wreckers was the first opera he programmed, and he feels it “always deserved a place in the repertoire – the reaction to our production shows that plenty of people agree”. He adds: “There are plenty of other operas by women that are equally worthy of this treatment and… more exciting rediscoveries to come.”

In 1910, at 52, Smyth joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, campaigning for women’s suffrage, giving up music for two years to further the cause. With Emmeline Pankhurst, she felt “the fiery inception of what was to become the deepest and closest of relationships”. The anthem Smyth wrote, The March of the Women, was first played on 21 January 1911 on the release of suffragettes who had been imprisoned during a protest of the previous year.

She and Pankhurst went on a campaign in March 1911 in response to adverse comments by a secretary of state about the Votes for Women campaign; they broke windows at the Houses of Parliament, and were arrested, and sent to Holloway Prison, held in adjoining cells. Smyth spent two months there, telling of cockroaches and mistreatment. It was there she made one of her most memorable works. On visiting her in prison, Thomas Beecham arrived in the courtyard at Holloway to see the spectacle of a “noble company of martyrs marching round it and singing lustily their war chant, while the composer, beaming approbation from an overlooking upper window, beat time in almost Bacchic frenzy with a toothbrush”.

The proudly unorthodox Smyth, photographed here in 1922, went everywhere with her dog (Credit: Getty Images)

Age did not wither Smyth’s passion. At 71, she met the writer Virginia Woolf, and was smitten: “I don’t think I have ever cared or anyone more profoundly,” she wrote in a diary. She was 25 years older than Woolf, who wrote “an old woman has fallen in love with me. It’s like being caught by a giant crab”. But she later wrote: “How we differ! Our minds are too entirely and integrally different: which is why we get on,” and their friendship endured to Woolf’s death in 1941.

In her last decades, Smyth lost her hearing and suffered tinnitus; she turned from music to writing, producing 10 mostly autobiographical tomes. She died in Woking, Surrey, in 1944, aged 86.

Leah Broad recalls a passage in Smyth’s diary: “She says the one thing she’s most scared about in dying is that she will no longer be able to control her musical legacy. She worried that when she goes, her music would die with her. And that sort of did happen, but that’s changed, it’s resurfaced now. And I’m so glad of that for her.”

A semi-staged version of Glyndebourne’s production of The Wreckers will be performed at BBC Proms on 24 July, which also features a number of works by Ethel Smyth during their season. A live recording of the Wreckers will be released on Glyndebourne Encore, Glyndebourne’s streaming platform, in August 2022.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.