The six lines that made a masterpiece

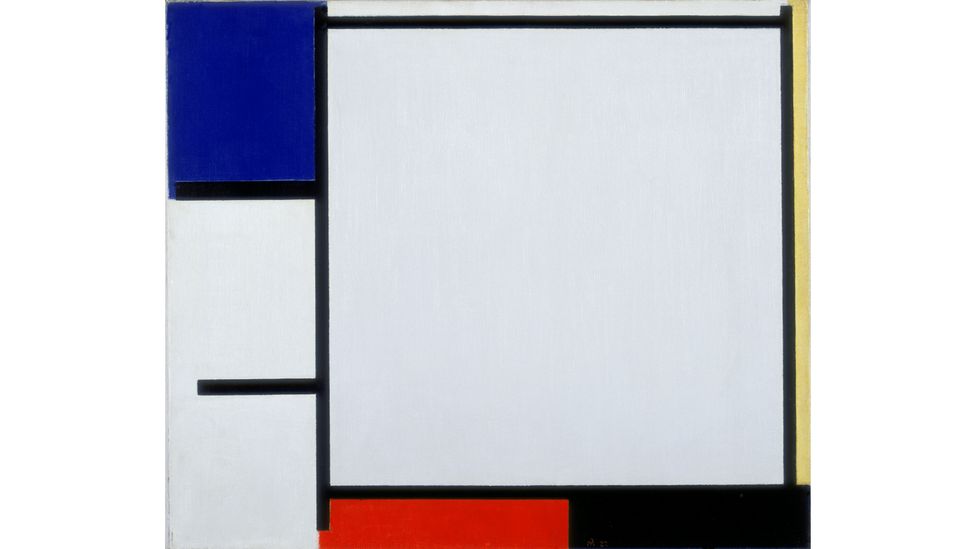

Six lines and five colours was all it took to make a masterpiece. By 1922, the modernist mission appeared to be complete. In Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Blue, Yellow, Red, Black and Grey, only primary colours prevail. The orange and cornflower blue that lingered the previous year had been banished from the grid, and a contemplative grey-white took centre stage. Western art had never seemed so simple or so accessible.

More like this:

– The artist who likes to blow things up

– The eerie allure of stone circles

– How fear shaped ancient mythology

In the same year, the Dutch painter took leave from his Paris studio to celebrate his 50th birthday with a retrospective of his work at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. Today, a century later, Mondrian’s 56 x 63cm Composition with Blue, Yellow, Red, Black and Grey is on permanent display in the museum’s basement, the characteristic “PM” monogram and “22” still visible in scratchy red paint.

Composition with Blue, Yellow, Red, Black and Grey (1922) broke artistic traditions to forge an entirely new approach in art (Credit: Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam)

Maurice Rummens, academic researcher at the Stedelijk Museum, describes the painting as “one of the spearheads” of the museum’s collection. It signalled a transformation in Mondrian’s style – and in painting. Representations of real objects and the use of perspective, seen in the artist’s landscapes at the turn of the century and continuing into his cubist period, were no longer modern enough for him. Instead, he turned to pure abstraction to communicate something more ambitious and intangible: the elementary and universal qualities of the cosmos.

“Vertical and horizontal lines are the expression of two opposing forces,” Mondrian later explained in a 1937 essay. “They exist everywhere and dominate everything; their reciprocal action constitutes ‘life’.”

Mondrian intended the combination of primary colours and bold geometric patterns to convey nature’s inherent connectivity in the most distilled and direct way possible. In a letter to fellow Dutch artist Theo Van Doesburg in 1915, he writes: “I always confine myself to expressing the eternal (closest to the spirit) and I do so in the simplest of external forms, in order to be able to express the inner meaning as lightly veiled as possible.”

“Mondrian was a trailblazer, in the sense that he was very radical, and in his concentration on the very essence of the image,” says Ulf Küster, curator of Mondrian Evolution, an exploration of Mondrian’s modernist journey currently showing at the Foundation Beyeler in Switzerland to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth.

“Minimalism is unthinkable without Mondrian,” he told BBC Culture. “He was one of the first who really did this, this totally non-representational work… If you see modern as something which breaks with all traditions and defines everything new, then Mondrian’s paintings of the 20s are very, very modern.”

While Mondrian’s earlier works, such as Tree (1912), are more figurative, they contain hints of his later Minimalist paintings (Credit: Mondrian/Holtzman Trust/ bpk/Staatsgalerie)

Hints of the revolutionary work that was to come nevertheless reveal themselves in Mondrian’s earlier pieces. The artist’s interest in grids, bold lines and right-angled compositions, for example, can be seen in landscapes where tree trunks slice the horizon (1902/3) or the numerous studies he made of a fenced meadow in 1905.

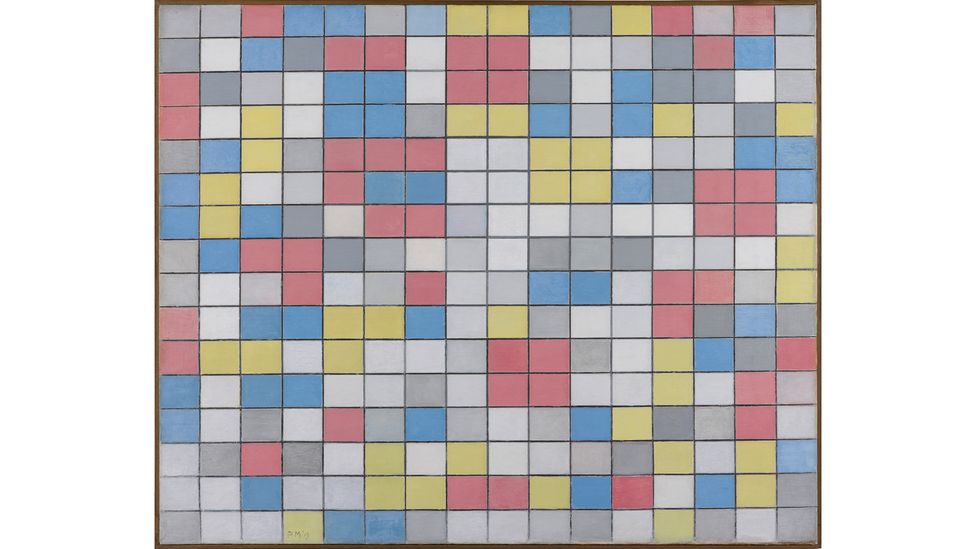

By 1922, Mondrian had adopted the principles of neoplasticism, an art movement also known as De Stijl which included Mondrian, Van Doesburg, Gerrit Rietveld, and Bart van der Leck among its leading members, and which advocated for pure, reductive compositions that were perfectly balanced. Mondrian disapproved of Van der Leck’s use of background and foreground, and opposed Van Doesburg and Van der Leck’s use of the diagonal – a determination to take the aesthetic all the way that created the iconic images he is known for today.

On the grid

Right-angles, he insisted, must stand upright; and colour now had to be primary, and most often pushed out to the extremities, giving primacy to white. In 1922, coloured planes exist in tension within a dislocated floating grid, keeping the eye and the painting in motion, and creating a composition that is both satisfying and unsettling.

Mondrian’s commitment to the grid was complete; the painter objected to the use of diagonals (Credit: Kunstmuseum Den Haag)

The simplicity of the finished piece belies its slow and laborious creation. Much of Mondrian’s working day was spent waiting and looking, staring at the canvas or pacing in his studio. “I am searching for the proper harmony of rhythm and unchanging proportion,” he wrote to Van Doesburg in 1919. “I cannot tell you how difficult it is.”

For Mondrian, however, balance did not imply perfection; a sense of the painter behind the piece was also important. In Composition with Blue, Yellow, Red, Black and Grey, colour bleeds beyond the imperfectly painted grid (Mondrian, it’s said, did not use a ruler), threatening to invade the whitish canvas. We are reminded of the painter’s part in making a masterpiece, and the interplay of the two opposing elements that he saw as central to his work: “individual” and “universal”.

Despite Mondrian’s orthodox and measured approach to his art, it was this human, “individual” side that drew bohemian society to his smoky Paris studio at 26 Rue du Départ, a living work of art laid out according to neoplastic principles.

Although his compositions could be seen as austere, Mondrian lived a bohemian lifestyle (Credit: Alamy)

“It was not at all true that he was isolated,” said Caro Verbeek, curator at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, where the world’s largest collection of Mondrian works reside. “He was a very charismatic person… He had a sense of humour, enjoyed hanging out with people. He loved women and women loved him.”

Mondrian’s circle of friends included the dancer, singer and actress Josephine Baker, who he saw as a kindred spirit. He filled his studio with the sound of his beloved jazz, and immersed himself in the cultural and intellectual life of Paris, going to the cinema, taking up dancing lessons, and attending concerts.

This love of music, in particular, brought an often-overlooked dimension to Mondrian’s paintings, currently explored at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag’s exhibition Mondrian Moves. The museum app pairs music and paintings, showing how the positioning of colours replicates the beats and the dance steps Mondrian knew so well, with the black, white and grey areas denoting non-tones or noise.

“Mondrian could hear, dance to and visualise neoplasticism,” Verbeek told BBC Culture. “All his neoplastic paintings were highly musical.” Verbeek hopes to take the experience a step further with Clapping to the beat of Piet, a tour which will use dance and clapped rhythms to bring everyone, including the visually impaired, closer to Mondrian’s work.

It was 1922 that saw Mondrian make the link between art and music more explicit. No doubt influenced by the experimental “noise concert” he had seen the previous year by Futurist Luigi Russolo, Mondrian proposed a “promenoir”, a concert space where abstract, electrical colour projections, so-called “sound colours”, would combine with music to create an immersive experience.

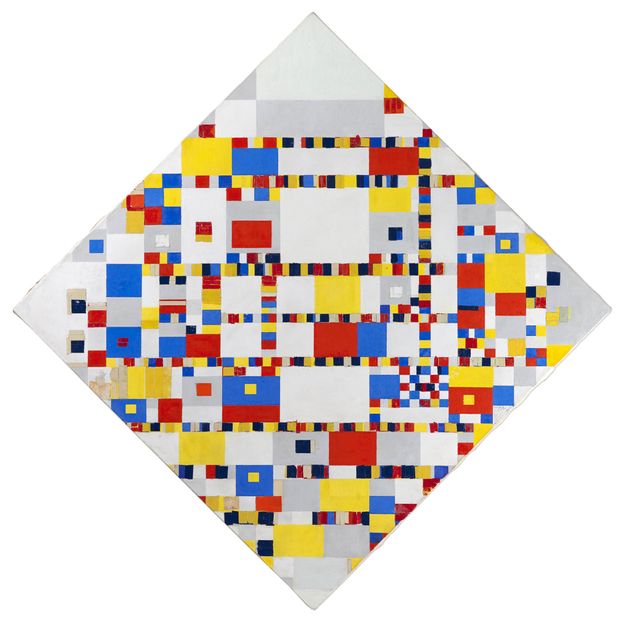

Mondrian’s last, unfinished work Victory Boogie Woogie – left incomplete in 1944 – symbolises the link between music and his paintings (Credit: ICN, Amsterdam)

This multi-sensory engagement with art, Verbeek explains, is also invited in Mondrian’s 1922 Composition with Blue, Yellow, Red, Black and Grey once you appreciate its musicality. “What I love about this composition is how he changes your sense of verticality and horizontality. It’s not just that you move your eyes, it’s also that your whole mindset changes… in the same plane,” she says. “That is how you are supposed to look at a Mondrian. Not as a picture that you scan, but as a change in direction, in movement, in rhythm, in pace.”

Contemplating a Mondrian, she explains, is a visceral experience: “The members of the Stijl want to evoke a bodily sensation, a very physical type of aesthetics.” Years later, Mondrian would go further, ascribing specific dances to his works. There was a Foxtrot series in the late 1920s, for example, and his final painting Victory Boogie Woogie (1942-4), was a celebration of the syncopated rhythms he adored.

Even the brush strokes perpetuate motion, explains Verbeek. The thin, vertical yellow plane, for example, is painted – counterintuitively – in painstaking horizontal strokes, creating that characteristic duality and opposition, while at the same time reminding us of the individual, the artist’s steady hand, within the universal.

Even appreciated at their most superficial level, Mondrian’s appealing and immediately recognisable grids have made a lasting impression, emboldening and democratising the art world and elevating the status of the graphic and the geometric.

We see the influence of Mondrian’s colour palette and sharp angles in Lichtenstein‘s Pop Art, and echoes of his checkerboards in the painted mosaics of Gerhard Richter. Architects from Slovakia to the US still experiment with the principles of De Stijl, and fashion brands such as Yves Saint Laurent, Hermès, Moschino and even Nike have all brought Mondrian’s grids to life on their runways.

In the Stedelijk Museum, where a century ago Mondrian raised a glass with friends, the 1922 masterpiece hangs innocently, its central white square staring blankly at passing visitors, directing their gaze on a perpetual journey in and around it. Is the work a pattern, a painting, a design or a dance?

For those who know, there’s music within, but most just look on inquisitively. The colours appear to flee the frame and the unfinished grid lines keep up their tease. “I think he just wanted to keep the image as open as possible,” muses the Beyeler’s Ulf Küster. “All good artists ask more questions than they give answers.”

Mondrian Evolution is at the Foundation Beyeler until 9 October 2022.

Mondrian & De Stijl is on permanent display at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Mondrian Moves runs until 25 September 2022.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.