The man who painted while bombs fell

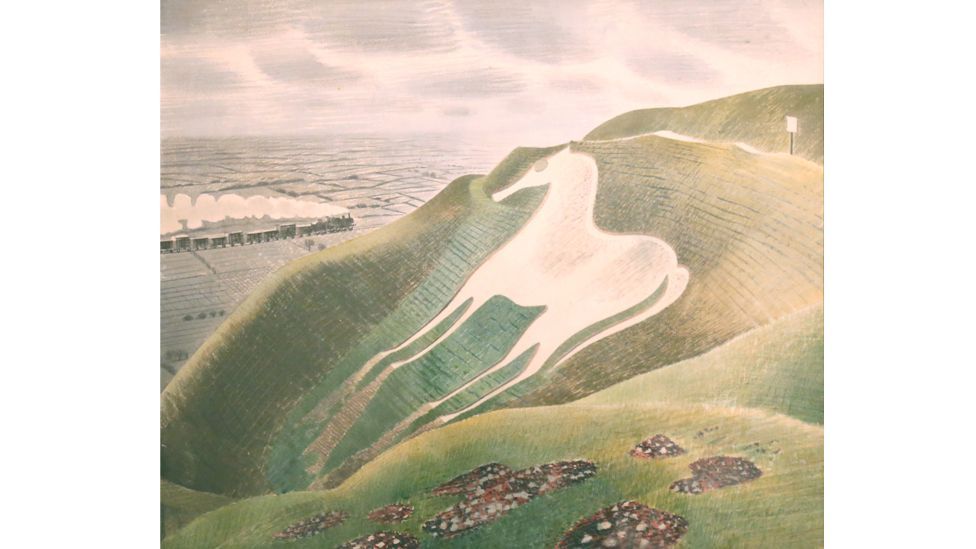

He was one of the greatest watercolourists of the 20th Century, loved for his paintings of famous English landmarks like the Westbury Horse, Beachy Head and the Long Man of Wilmington. He was a chronicler of mid-century British life, whose subject matter is now seen as the epitome of traditional Englishness: tea on the lawn, cricket on the green, and keeping the home fires burning.

More like this:

– Haunting paintings from the battlefields of war

– The story of a painting that fought Fascism

While Eric Ravilious was a master painter, designer and engraver, his other great role was as a war artist. Among the finest and most prolific of his generation, he died while on active duty during World War Two. This year marks the 80th anniversary of his death which, with the release of a new film on Ravilious, his life and his war art, raises the question: what makes a great war artist?

Watercolourist Eric Ravilious chronicled mid-century British life, painting landmarks including the Westbury Horse (Credit: Private collection, Towner, Eastbourne/ Foxtrot Films)

Joining the debate is Ai Weiwei, the Chinese artist and documentary filmmaker, himself a war artist, having made work responding to conflict. “In my opinion, Eric Ravilious is great because he uses accessible language and a calm manner to express our understanding of the cruelty of life in reality, in such a way that everyone can relate to,” he tells BBC Culture.

Ravilious’s war art is outstanding for its “innocence and purity”, observes Mr Ai. Certainly Ravilious’s character – his lightheartedness and sense of joy – infuse the watercolour HMS Glorious in the Arctic, 1940, in which a ship sails forth, more pleasure cruiser than vessel of destruction, while planes glide gaily overhead in an exquisite composition of deceptive simplicity. Or his painting Dangerous Work at Low Tide, 1940, depicting naval officers at the oyster beds in Whitstable, Kent, on a mission to defuse a German mine. Ravilious’s soft pastel colours, cartoon-like figures, tranquil tide pools and sky, can’t help but also defuse the apparent danger or threat.

Contrast these soft-focus, dreamy visions with work by his war artist contemporaries, such as Henry Moore’s Shelterers in the Tube, 1941, in which piles of dark bodies lie slumped on a sooty floor, or sitting bolt upright in a rictus of anxiety. Or Edward Ardizzone’s Scout Cars of a Regiment of Hussars Liberating a Stalag, 1945; a pathetic scene of starved, tortured figures clinging to wire, unable to leave. One wonders what Ravilious would have made of these assignments, given that he approached all subjects with a kind of irrepressible joy and optimism.

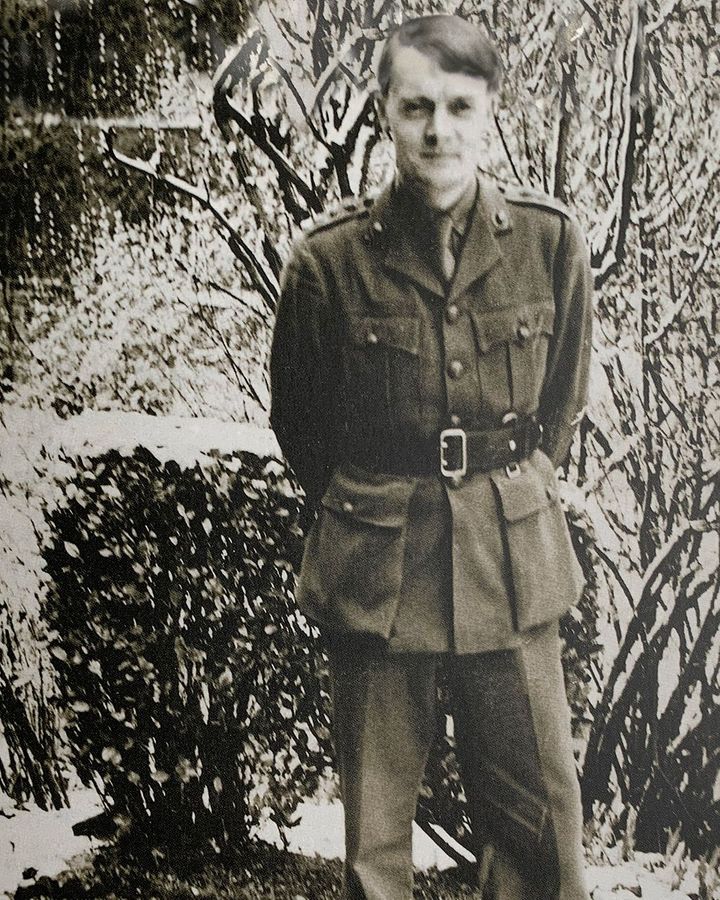

Captain Eric Ravilious was assigned to the Admiralty and then the RAF – a new documentary, Drawn to War, tells the story of his life and work (Credit: Private collection)

To make sense of Ravilious’s style, one has to look to his background and character. Ravilious was known as an affable personality who loved dancing and pub games, and was always whistling. He had an “extraordinary Pan-like charm”, according to his artist friend, John Lake. Artist Edward Bawden, a lifelong friend he met at the Royal College of Art (RCA), where they both trained in the 1930s, called him “the Boy” because of his youthful vigour. The artist Douglas Percy Bliss, another RCA friend, said: “I never saw him depressed… Even when he fell in love – and that was frequently – he was never submerged by disappointment. Cheerfulness kept creeping in.”

Ravilious had met his future wife, Tirzah Garwood, when they were both at Eastbourne College. Tirzah, or Tush, was a brilliant artist and engraver in her own right. She was 18, he was 22. Aware of his reputation as a flirt, she was anxious when he asked her to go for a walk, as to how “not-quite-a-gentleman might behave under such intimate circumstances”. He made a drawing of her, which seems to have won her confidence: they were married within a year.

He went into the design department at the RCA, which shaped him as an outstanding decorative designer and wood-engraver. His RCA teacher, Paul Nash, had been a war artist in World War One, and would be one of his greatest influences. Struggling to make ends meet, it was his commercial work, such as his Wedgwood commemorative china for Edward VIII, George VI and Queen Elizabeth II, that paid the bills. He also designed jackets for books, magazines and a long run of covers for Wisden, the “bible of cricket”.

As the threat of war loomed, Ravilious showed his anxiety about the impending conflict in a letter he wrote in September 1937, submitting work to the Artists Against Fascism and War exhibition: “Dear Sir, please accept my painting… Like many artists I am drawn to war as a subject, but deeply troubled by it…”

Tea at Furlongs was painted as war began – Alan Bennett notes: “It’s seemingly a very peaceful scene but its emptiness is ominous” (Credit: Fry Art Gallery/ Foxtrot Films)

When war did break out in Europe, Kenneth Clark, then director of the National Gallery in London, appointed artists to respond to the conflict and to create a permanent record of war from an eye-witness point of view. More than 300 artists were commissioned by the War Artists Advisory Committee, the scheme Clark devised, including Stanley Spencer, Henry Moore, Bawden, Paul and John Nash. Ravilious got his commission on Christmas Eve, 1939.

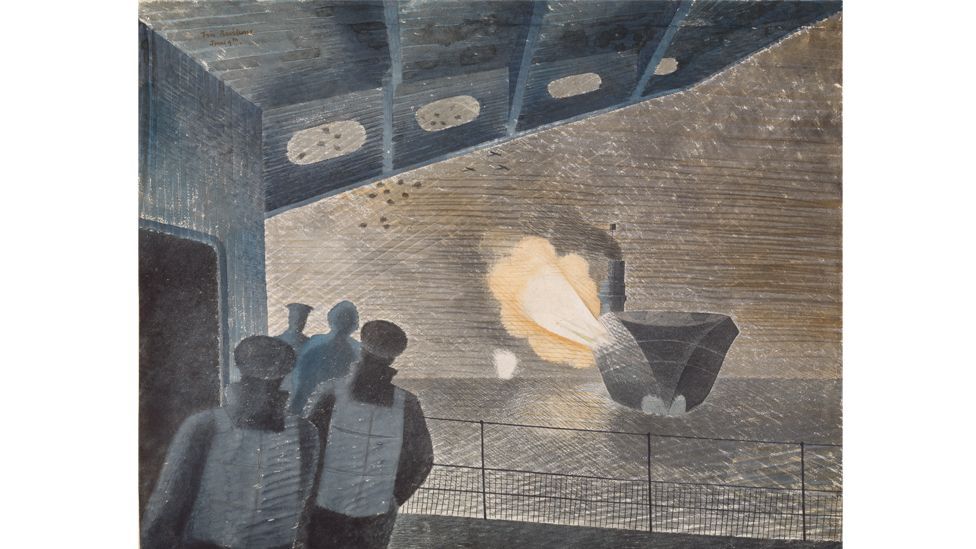

Assigned to the Admiralty, Ravilious set to work, painting ships and submarines at the Royal Navy Barracks at Chatham and coastal defences at Newhaven. Posted abroad, he painted fjjords in Norway and aircrafts over Iceland, always working in his distinctive style. Ravilious created around 100 art works while on commission as a war artist. He seems to have loved his war-artist duty; “I enjoyed it a lot, even the bombing which is wonderful fireworks,” he reported in 1940, in the midst of a grim sea battle off Norway. The following year, by this time with the RAF, he wrote home: “It was more lovely than words can say, flying over the moors and the coast today in an open plane, just floating on great curly clouds and perfectly still and cool.”

His war art drew criticism from some of the military hierarchy for not tackling panoramic views or varying his work’s shape and size, or for its detached or innocent stance. However, Alan Ross, in his book Colours of War, praised the detached stance of Ravilious’s art: “The battle area may be a long way off but this, tenuously, is where it all begins. In most of Ravilious’s war pictures, ships and sea, aircraft and landscape blend together, camouflage having transformed machinery and nature into a single abstract.”

Art of war and peace

However, Ai Weiwei believes staying true to his style was one of Ravilious’s greatest strengths: “From his paintings I can see his firm control of the watercolour, [his] calm expression, attention to detail and meticulous care, showing his extraordinary insight and expression.” He adds: “He did not focus on style, but rather on his attitude and way of expression. He added a strong personal touch to the themes that he depicted. That is why he is great.”

There is a deceptive lightheartedness and simplicity to works such as HMS Glorious in the Arctic, 1940 (Credit: Imperial War Museums/ Foxtrot Films)

In July 1940, an exhibition of war artists’ work was hung in London’s National Gallery. Paris Agar, a senior curator specialising in art at the Imperial War Museum (IWM), notes it was the first public exhibition of art from World War Two, and the speed of its display was a great achievement. Despite any criticism, Ravilious “was the artist with most works on display”. The collection was later dispersed to galleries and museums all over the world.

Fifty of the works Ravilious created as a war artist were retained in the IWM collection. “Using watercolour, he could work at speed,” says Agar. “His work showed people what was going on outside Britain – his art made in Norway in particular.” Ravilious was “a shining light… [whose] work is aesthetically pleasing and accessible,” she says. He often worked in very dangerous situations; sometimes painting on the deck of a military ship with Spitfires flying overhead, or moving at such speed his paints might be flying everywhere; in the light of the midnight Sun, making him more of a target; and sketching the evacuation of Narvik in Norway from a ship that, a few days later, was sunk.

In his last letter to his wife, Tirzah, he wrote from abroad of having “an unbelievable lunch of caviar, pate and cheese”, and asked if she’d like a pair of gloves made of “sealskin with fur on the back”, telling her to draw around her hand so he could get the size. “Goodbye darling. Hope you feel well again,” he signed off. This was three days before he took off on a search-and-rescue mission, on 2 September 1942. The plane he was flying in went missing off the coast of Iceland. The wreckage was never recovered. He was the first of three official war artists to die during the conflict.

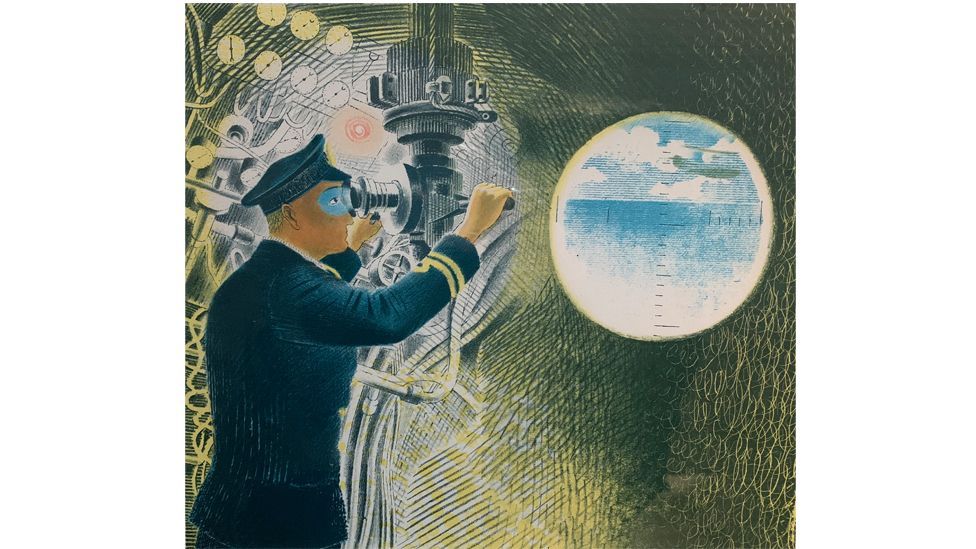

Three decades after Ravilious’s death, a portfolio of his art was discovered under fellow artist Edward Bawden’s bed, where it had been stored for safekeeping. Ravilious had made a series of paintings and lithographs inside submarines, including Commander of a Submarine Looking Through a Periscope, featuring fine crosshatched lines and a graphic depiction of the officer’s view above sea level; and The Ward Room, depicting a mess cabin, both made in 1941. Some of these had been rejected by the War Office.

Three decades after his death, a portfolio of Ravilious’s war art was discovered, including Commander of a Submarine Looking Through a Periscope (Credit: Foxtrot Films)

“They were ahead of their time,” Margy Kinmonth, director of the documentary Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War, tells BBC Culture. She says the fact that many of these works went into private collections “is part of the reason we know him so little”. Her film draws together many of the unseen artworks, and features interviews with Ai Weiwei, British artist Grayson Perry, and writers Alan Bennett and Robert MacFarlane, exploring what they feel made Ravilious a great – and underrated – artist.

Kinmonth, whose previous films include Royal Paintbox, made with Prince Charles on the subject of Royal art, and War Art with Eddie Redmayne, set out to make “a portrait of a marriage”; her script was based on Tirzah’s autobiography, which she calls “an important feminist document… powerful, strong, immediate, funny”. She also had full access to the family archive of photographs and Eric’s letters: a prolific letter writer, he sometimes sent four or five a day.

The writer and actor Alan Bennett says in the film that he has long tried to define what it is to be English, but is sure “Ravilious is part of it”. He feels the artist “might not be properly estimated… [and that’s] because he’s so easy to like. He’s so loved yet he nevertheless is a shared secret”. He appreciates the childlike and innocent aspect to Ravilious’s style, but notes a Surreal edginess in it, citing the 1939 painting Tea at Furlongs, the flint Sussex cottage Eric and Tirzah shared with artist Penny Angus: “It’s seemingly a very peaceful scene but its emptiness is ominous, and I think it could equally be called Munich, 1938.”

Ravilious made more than 100 artworks as a war artist, including HMS Ark Royal in Action (Credit: Imperial War Museum)

Artist Grayson Perry recalls his time spent living in Great Bardfield, in north Essex, where Ravilious once lived and which was an important artists’ community from 1930 to 1970. He says paintings, such as A Farmhouse Bedroom 1939, “take me back to my childhood, wandering in an imaginary world, across the stubble”, he says, to houses that “didn’t even have electricity… very primitive, you can almost smell the damp”. He concludes: “What Ravilious does very well is he takes what seems like unprepossessing subjects and makes them into masterpieces.”

The IWM continues to commission war artists to record conflicts in which Britain is involved. Agar highlights the work in recent decades by artists such as Linda Kitson, who was the first female artist to go into a war zone, when she responded to the Falklands War in the early 1980s; Peter Howson, who responded to the Bosnian war in the 1990s; Langlands & Bell in 2002 and Mark Neville in 2014, who both produced art about Afghanistan.

In August 2020, Ai Weiwei’s artwork History of Bombs was installed at IWM, which commissioned it. It was part of IWM’s Refugees season, reflecting the personal stories of people forced to flee their homes owing to conflict. For the site-specific work, he covered the atrium’s floor in fabric printed with images of bombs, including the Soviet Union’s Tsar Bomba, the most powerful nuclear weapon ever made. He says he “shares some common points” with Ravilious because “we are both phenomenologists,” he says, referring to those who study phenomena and how we experience them. “For History of Bombs… I researched who created these bombs, when they were used, and how to talk about the origin of war in a more conceptual and rational way.” He says he relates this to Eric Ravilious’s works “[which] give us an almost Surrealist sense because of their calmness and a kind of a detached angle of an observer”.

Ravilious went missing, presumed dead, while flying over Iceland, though the wreck was never found (Credit: Imperial War Museums/ Foxtrot Films)

Ai Weiwei reiterates his belief in Ravilious as a great artist, and great war artist to boot. “His war paintings are very much like childrens’ depiction of war,” he tells BBC Culture. “I saw a lot of paintings by refugee children and adults in a refugee camp in Iraq. They are very similar to Eric Ravilious’s paintings. In their respective ways, they all depicted war in an innocent and almost naïve manner. In fact, the brutality of war cannot be understood by everyone because it is inhuman and inhumane.” He concludes: “Seen in this light, what Eric Ravilious did was enable us to look at war with a calm mind. This is truly special.”

Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War is at selected UK cinemas now.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.