The greatest Star Trek episode ever

When it comes to big film and TV franchises, few are as gratifyingly diverse these days as the Star Trek universe. Creator Gene Rodenberry had a fundamental belief in the innate goodness of diversity – “[It] contains as many treasures as those waiting for us on other worlds. We will find it impossible to fear diversity and to enter the future at the same time,” he once wrote – and that ethos has been increasingly reflected in the different Star Trek iterations. Star Trek: Picard, which is currently in its second season, features an array of great, complex characters played by actors of colour, including Whoopi Goldberg, Michelle Hurd, Isa Briones and Santiago Cabrera. Meanwhile Star Trek: Discovery, just finishing its fourth series, includes a black woman as its ship’s captain and series lead – Sonequa Martin-Green’s Captain Michael Burnham.

More like this:

– Why Trekkies are the greatest fans

– Buffy at 25: how tainted is it?

– 10 of the best TV shows to watch in March

But the franchise, which has encompassed 10 different captains in its voyage so far, has not always provided adequate representation of marginalised voices or told their stories sympathetically or in ways that avoid crass stereotyping. The original series, for example, may have been ground-breaking in the 1960s for featuring Lieutenant Uhura, played by African-American actor Nichelle Nichols, who created US TV history by kissing her white captain – but Martin Luther King Jr had to beg her to not leave the show when she grew tired of how little her character participated in storylines.

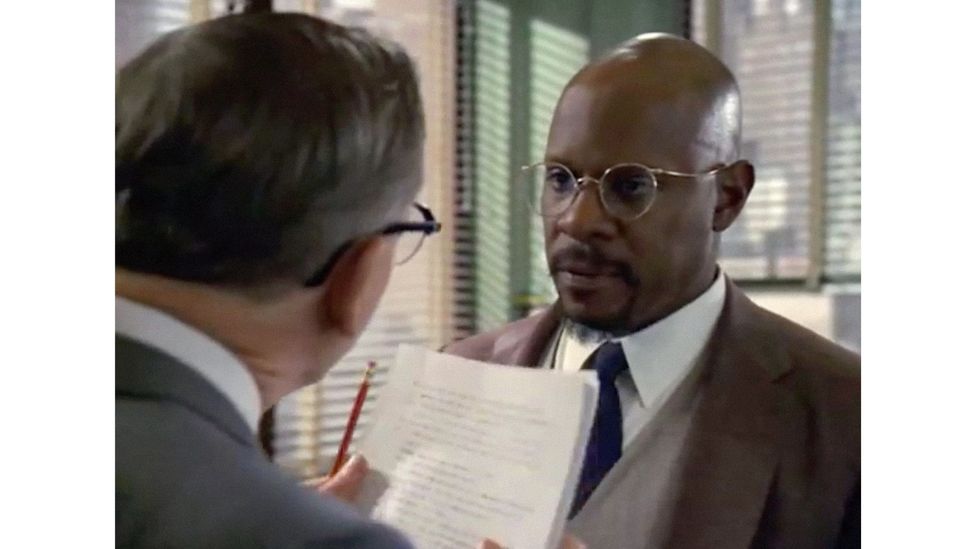

Far Beyond the Stars sees Benjamin Sisko hallucinate that he is Benny, a sci-fi writer in 1950s New York (Credit: Star Trek: Deep Space Nine / Paramount Television)

“She wanted to quit that show,” says African-American sci-fi novelist Steven Barnes. “Because she felt that she was not being allowed to do anything. But there are little girls who grew up and are now in the astronaut programmes, who saw Uhura and they believed. They believed that there was something more than poverty.”

Also, in both the original Star Trek series and its successor, The Next Generation, there was a dispiriting trade-off between inspiring casting – as well as Nichols, Japanese-American actor George Takei was also prominent in the first Star Trek crew – and problematic storylines, suggests Dan Hassler-Forest, pop cultural theorist and assistant professor of media studies at Utrecht University: he points as an example to the fact that while “the first inter-racial kiss was a big historic moment, in the context of the plot they’re being forced to [kiss] against their will by mind-controlling aliens”. It is notable too that the villainous Klingons were conceived as darker-skinned, while The Next Generation episode Code of Honour featured a human warrior species ruled by their sexual appetites played exclusively by African-American actors.

A watershed moment

So what was the turning point that moved Star Trek away from these dated follies to the kind of thoughtful, genuinely progressive representation seen in Discovery and Picard? For this answer we have to look back to two pivotal years: 1998 and 1953. The former was when Far Beyond the Stars, an episode of Deep Space Nine, the fourth show in the Star Trek franchise, was first shown – and the latter was the year the episode was based in. It was a huge departure for the series, the Star Trek universe and science-fiction at the time more generally, as instead of featuring 24th-century spaceships, it took the audience back to a post-war New York where police brutality was common and African-Americans weren’t allowed to live everyday lives without constant racist persecution.

The episode was directed by the show’s star Avery Brooks, who played Deep Space Nine captain Benjamin Sisko and was the Star Trek franchise’s first African-American leading man. Brooks had already starred in another ground-breaking show, 1989’s crime drama A Man Called Hawk, which also featured legendary Shakespearean actor Moses Gunn. Although it only aired for 13 episodes, it was significant for its nuanced portrayal of African-American culture; Hawk was a mythological street hero who loved African art and jazz, and Brooks made him authentic by enlisting his mentor, writer and thinker Calvin Hernton, to give him advice. “I asked him specifically to help me do this,” Brooks said in a 2008 interview. “[With Hawk] We are looking through the world in brown eyes. It was very carefully crafted – visually, music[ally] and culturally.”

Brooks, who started an all-black theatre company called Psuekay when he was at Ohio’s Oberlin college in the 1960s, wanted to take roles that offered African-American children hope, and with Star Trek’s Sisko, he thought he could show them how people of their colour could thrive in positions of power. The character introduced at the opening of Deep Space Nine was quite complex – he was angry that his wife had been killed and, uniquely among the Star Trek crew, he didn’t really want to be in space but back on Earth with his son, who now had only one parent. Brooks was also drawn to the role so that he could present to viewers a strong African-American father figure – in fact, he was so committed to this paternal element that he considered his on-screen son, Jake played by Cirroc Lofton, as family in real life, inviting him to join the Brooks’ family holidays.

As well being a captain, Sisko was also a prophet figure (an Emissary of the Prophets within Star Trek lore, specifically), making him more spiritual (and less scientific) than previous Star Trek captains. For Brooks, this fitted with the character’s African lineage: “Everywhere African people are, there’s a relationship to the spiritual and the divine,” he said in a 2007 interview.

Avery Brooks, who played Deep Space Nine captain Sisko, was Star Trek’s first African-American leading man (Credit: Alamy)

At the same time as being spiritual, Sisko is also presented at odds with the chain of command. He blames his wife’s death on former captain, Jean-Luc Picard (Sir Patrick Stewart), who unwittingly murdered her when he was incorporated into cyborg collective the Borg. When the Star Trek captains go head-to-head in Deep Space Nine’s opening episode, “it establishes Sisko’s character very well – that he is not deferential to Picard,” says Kendra James, former managing editor at StarTrek.com. “He really stood out at the time because he was this black man being allowed to dress down this very well established and respected white actor.” After this bold opening, however, Sisko does become more diplomatic, and like a politician, as the series progresses and he deals with the various conflicts that arise among his crew. It’s a smoothing out of the character that feels a bit jarring coming from the white writing team – when, for example, Colm Meaney’s Irish officer Miles O’Brien was allowed to be more nuanced by comparison, at once argumentative and quick to display anger and a loving father and husband.

But then as Deep Space Nine approached its sixth season, the writers decided to take more risks and create an ongoing storyline that saw Sisko having hallucinations. They were brought on by the stress of a long war with a hostile superpower that started in season two, during which his friend died, leading him to contemplate leaving the Starfleet.

It’s in this context that the remarkable Far Beyond the Stars takes place: Sisko’s father, played by Brock Peters (best known for playing Tom Robinson in the 1962 film of To Kill A Mockingbird) is visiting from Earth and during a tense conversation with him, Sisko becomes unwell and is taken for treatment. He appears to be dying and the episode then shifts into his hallucinations about a 1950s New York, in which he and other members of the Deep Space Nine crew are working on a science-fiction magazine called Incredible Tales.

In his hallucination, Sisko becomes Benny Russell, an African-American writer who passionately wants to create stories with black characters, but has to suffer the indignation of his work being censored and being told to stay at home during a staff photo for the comic – “It’s not personal Benny, but as far as our readers are concerned, Benny Russell is as white as they are. Let’s just keep it that way,” says his editor.

Star Trek has a long history of time-travelling episodes – often referred to as Holodeck episodes – where a computer simulator would whisk them to a different era, allowing the characters to play historical figures and briefly turning the sci-fi show into a period drama. These can often be some of the more light-hearted episodes, such as The Next Generation’s Elementary, Dear Data, where Commander Data becomes Sherlock Holmes or Deep Space Nine’s Badda-Bing, Badda-Bang in which the crew find themselves in a simulation of Las Vegas in the 1960s, in which the computer has deliberately “programmed out” the racial tensions of the era.

An unflinching period drama

In Far Beyond the Stars, by contrast, none of the prejudice of the 1950s is erased. On top of his experiences in his workplace, Benny is viciously assaulted by two racist policemen, witnesses a friend (who is actually his son, Jake Sisko) stabbed to death and eventually has a nervous breakdown. In a 2007 interview Brooks said making the episode “was one of the proudest moments I hold in my years in Star Trek”. James recalls a famous story about the episode, that in a scene where Brooks was “on the ground crying, he never broke that show of emotion even when ‘cut’ was called. He just kept crying because he was feeling that emotion so much.”

This episode also benefited from Brooks’ meticulous direction (he held a master in fine arts degree in both acting and directing) which, among other things, concentrated on the finer details of Benny’s character, imbuing him with a rich African-American and African heritage. “That porkpie hat… and the piano in the kitchen [were references to] Thelonious Monk,” he said in 2013. “… [and Benny’s apartment featured] a real door from the Dogon tribe in Mali, [the African people] who discovered [the star] Sirius B hundreds of years before people in the West.”

Benny’s African-American and African heritage were reflected in details like the objects in his apartment (Credit: Star Trek: Deep Space Nine / Paramount Television)

Meanwhile the tragic romance between Benny and his fiancée Cassie treads similar ground to James Baldwin’s novel If Beale Street Could Talk, which is fitting as, in that same 2013 interview, Brooks quoted James Baldwin’s The Price of a Ticket, in acknowledging the forebears who had paid “the price of the ticket” for his acting career. “The reason I sit here before you is not because of me… it’s because of people named and unnamed who have prayed for me, who have sung for me, who have struggled for me,” he continued.

For Barnes, who wrote the novelisation of the episode, Far Beyond the Stars was an important piece of sci-fi history and it resonated with his life as a black sci-fi writer, who, along with likes of Samuel “Chip” Delany and Octavia E Butler, has been an outlier in a white-dominated field. “Benny was something we had never seen before in television,” he says. “Benny represented Delany who was writing sci-fi relatively early and could not have his photo on his books, could not really talk about himself. He created entertainment for children of the people who didn’t consider him human and would spit on him. He left the field, as it was not supporting him and he went into academia.”

“Then Butler came into the field and they would put green people on the cover of her books but not black people. I didn’t let this embitter me because then my enemies win.”

Far Beyond the Stars paved the way for the Star Trek franchise to embrace more sophisticated representation, and its legacy can be seen in the way Discovery boasts multiple storylines about systemic racism, queerness and non-binary issues. But it’s also arguably far bolder in its treatment of race and racism than anything that has followed in the Star Trek world.

“I find Discovery kind of insufferable,” Hassler-Forest admits. “Because it sometimes feels more like a TED talk about social injustice. But Far Beyond the Stars is a rare episode that is so compelling because it’s about the historical legacy and the complexities of racial politics.”

The power of Far Beyond the Stars still resonates today. As a writer of colour, like the character Benny, I work in a white dominated industry (92% of UK journalists are white) and every single person who commissions my articles is white. I’ve been told by international publications that stories from marginalised communities “aren’t something their readers are interested in” and my ideas are “too niche”. It feels like the language used is less harsh compared to that which the Bennys of this world would have encountered in 1953, but the result is the same as – like Benny, we’re all operating within a white chain of command.

More widely, Far Beyond the Stars offered a blueprint for how sci-fi can weave tough contemporary issues, such as systemic racism, into a compelling storyline. It’s quite amazing to think that the most disorientating world Star Trek has portrayed was not somewhere in space but New York in 1953, reminding viewers that any threat humankind, and people of colour in particular, faced from aliens could hardly be worse than the hatred that burns within our own society.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.