Seven artworks exploding a myth

From its beginnings, Surrealism’s objective was to subvert the things most people believed to be the very foundations of modern civilisation: logic, convention and reasoning. Surrealism promised intellectual liberty to its followers – initially writers, and only latterly visual artists. These artists aimed to open doorways on to worlds that political authorities can’t penetrate: the imagination, impulses and dreams.

More like this:

– The woman written out of history

– The meanings hidden in a masterpiece

– The paintings that reveal the truth

And subsequently a history was told by scholars to define Surrealism. This involved a condensed cast of (mostly male) heroes including the movement’s father André Breton, who had written the first Surrealist manifesto in 1924. Mostly, it involved his disciples – artists like Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Max Ernst. It also became intimately linked with Western cities: particularly Paris and New York.

“That’s how histories are made and simplified for people to get a grip on,” Matthew Gale, curator of Surrealism Beyond Borders, an exhibition at London’s Tate Modern, tells BBC Culture. “Historians complicate them by doing research.” This research, which was undertaken by Gale, his co-curator Stephanie D’Alessandro and a team of scholars, involved going back to original publications and exhibition catalogues, and discovering many lesser-known artists that deserve re-examination. “We’ve approached it from a transnational and transhistorical point of view,” says Gale, “Surrealism is not a style, it’s a state of mind that leads to a free individual creativity.”

To demonstrate this new perspective, Matthew Gale reveals how artists from six continents – Australasia, Asia, Europe, North America, Central America and Africa – were inspired by Surrealist techniques and ideas.

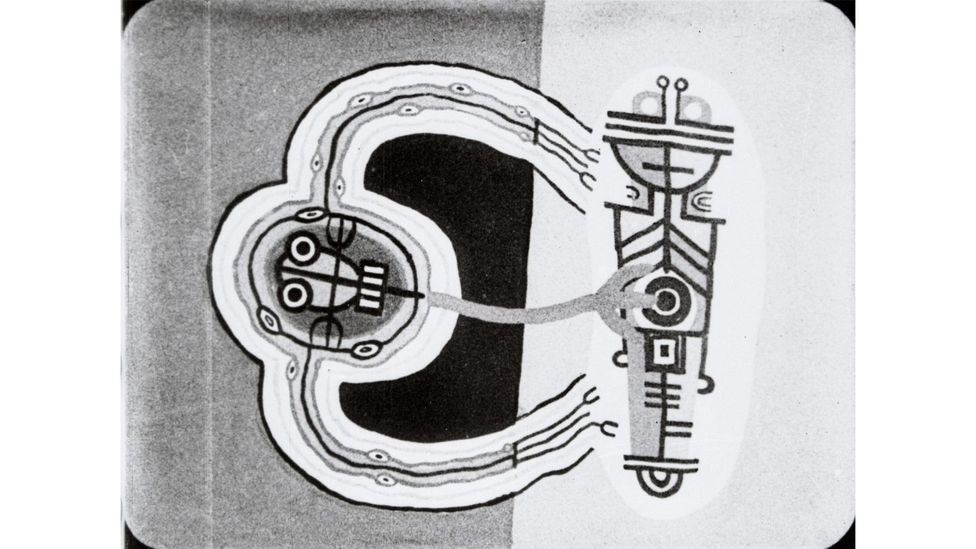

Tusalava (1929) by Len Lye, New Zealand

One of the exhibition’s most extraordinary artworks is Tusalava (1929), a 10-minute animated film by New Zealand-born Len Lye. In it, primordial, worm-like forms wriggle out of a void, give birth to a humanoid figure, and then vanquish him. Lye was inspired by tales of the witchetty grub which came from the Arrernte people of Central Australia, and used imagery inspired by Māori and Samoan art. But these cross-cultural interests were combined with a technique beloved of the Surrealists. “It is painted directly on to the film, so it is a sort of doodling automatism made directly on to the celluloid,” Gale explains. Automatism is a characteristic Surrealist process that involves “free” writing or drawing, in an attempt to decouple expression from conscious control. The film – the result of two years’ worth of painstaking work – brings the spectacle of automatism breathtakingly to life.

Tusalava (1929) by Len Lye (Credit: Stills Collection, Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision / Courtesy of the Len Lye Foundation)

Sea (1929) by Koga Harue, Japan

With its factory, sea vessels and airship, Japanese artist Koga Harue’s monumental painting The Sea (1929) seems to be a paean to technology. This was an intentional rebellion against what Koga and his colleagues disliked in European Surrealism. They thought that Breton and his followers were decadent in disengaging with modern progress, and proposed a ‘”scientific” Surrealism in Japan. But they retained a technique favoured by the Surrealists in Paris: the combination of otherwise disassociated symbols to create magical effects. “What Koga Harue does is to show that through unexpected juxtapositions, there is something perhaps irrational in the rational,” Gale says. This is born out in uncanny visual relationships, such as the oversized Western bather contrasted with a factory’s clockwork logic, and the mysterious world of the seabed confronting the deadly stealth of a submarine.

Sea (1929) by Koga Harue (Credit: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo / MOMAT/DNPartcom)

Lobster Telephone (1938) by Salvador Dalí, Spain

Surrealism was born in Europe, and Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone, made in Paris in 1938, is one of its most famous icons. “It is a brilliant combination of unconnected things that becomes an object that is both functional and completely irrational,” Gale explains. “It’s a totally marvelous thing, made at that critical moment when Dalí is managing to establish himself as a celebrity around the world.” Indeed, one of the things that popularised Surrealism internationally was Dalí’s involvement in advertising and with Hollywood. He devised a dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) and briefly worked at Walt Disney Studios. “You can’t downplay the significance of Dalí’s celebrity moment because that’s what fixed it in people’s minds,” says Gale. Lobster Telephone was made for Edward James, the London collector, for his house in Wimpole Street. “As far as I am aware James actually used these phones,” Gale explained. “I’m not sure what one does with the claws…”

Lobster Telephone (1938) by Salvador Dalí (Credit: Tate Purchased 1981 / Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS)

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943) by Dorothea Tanning, USA

The traditional story of Surrealism tells us that it began in Europe and migrated to the US at the outbreak of World War Two, as intellectuals and artists fled from the Nazis. But Gale disagrees. “There were different points of contact and different points of departure for Surrealism within the United States – much more complex than just the Europeans arriving in 1940.” Dorothea Tanning, however, did benefit from the appearance of European Surrealists in the US. She saw a Surrealist exhibition in New York in 1936, and visited Paris three years later. She married Max Ernst after his emigration to the USA, and the pair eventually lived together in a remote outpost of the Arizona desert. “She found in Surrealism a sense of autobiographical release,” says Gale, “a way to plumb her personal experience, and find a way to express that through her work. The dreamscape that is implied both by the imagery and the title is a fundamental thread in Surrealism that you can penetrate to the subconscious to elicit new poetic and pictorial images, but also to release those repressed ideas and fears.” Eine Kleine Nachtmusik hints at imponderable desires, and acts with its ambiguous symbols. These include a life-sized doll, and a girl whose approach to an ominously open door is blocked by an oversized sunflower with ripped petals.

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943) by Dorothea Tanning (Credit: Tate / DACS, 2022)

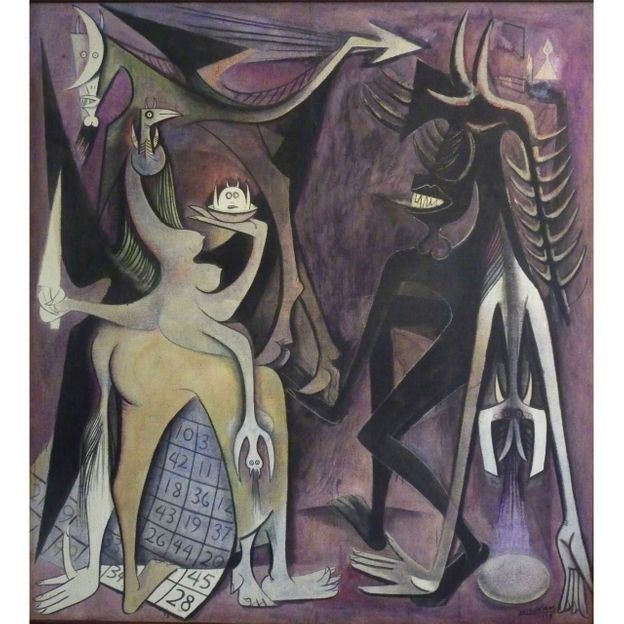

Bélial Empereur des Mooches (1948) by Wilfredo Lam, Cuba

Wilfredo Lam’s art exposes an incredibly rich vein of Surrealism in South America. His father was Chinese, his mother was Afro-Cuban, and after studying in Cuba he travelled through Europe to work alongside Surrealists in Paris. On the way, he fought on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. Leaving Europe at the outset of World War Two, he found himself on the same ship as André Breton. “When Lam returned to Cuba, he found it a corrupt place, and was deeply shocked by its racism, and its financial and social inequality. He turned this into the fuel for his art which drew upon Afro-Cuban traditions, and turned them against the dominant society – and by implication against the neo-colonialism of the United States,” says Gale. Bélial Empereur des Mooches translates as “Belial Emperor of the Flies”. Venus, the Roman goddess of love, stands on the left, and on the right is a figure who is a hybrid of Mars, the god of war, and Changó, the Yoruba thunder god. The title refers to Belial, an alternative name for the devil in Christianity, and also uses forms reminiscent of Vooduo ceremonies Lam witnessed alongside Breton in Haiti. It’s testament to one important thread of international Surrealism – its adaptability to local traditions and beliefs, and its frequently vocal opposition to colonialism.

Bélial Empereur des Mooches (1948) by Wilfredo Lam (Private collection / SDO Wifredo Lam/ DACS, 2022)

Untitled (1967) by Malangatana Ngwenya, Mozambique

Malangatana Ngwenya was a Mozambican artist, whose Untitled (1967) gives us one example of how Surrealism had an impact in Africa. A committed Marxist and a member of Frelimo, the anti-Portuguese freedom movement during the time of Mozambique’s struggle for independence, he bore witness to the tragic civil war that followed separation from Portugal. In the 1960s, Malangatana was invited to exhibit alongside other Surrealists at the Luanda Museum in Angola. “He is an interesting figure in relation to Surrealism because other people saw his work and said: ‘this looks like Surrealism’. He later showed work in Surrealist exhibitions in Portugal and in Chicago. He is a Surrealist by invitation,” explained Gale. Like a medieval depiction of hell, Untitled shows figures dismembered and eaten alive by monsters – Malangatana has conveyed a historical tragedy as if perceived at the height of a fever dream.

Untitled (1967) by Malangatana Ngwenya (Credit: Tate)

Long Distance (1976-2005) by Ted Joans, USA

Artists from around the globe were electrified by the promise of imaginative freedom offered by Surrealism. They used Surrealist techniques like automatism, juxtaposition and dream imagery to explore the inner life of the mind, sometimes using indigenous cultural forms to make a political – often anti-colonialist – point. The US poet, musician and artist Ted Joans epitomises the uniquely international character of Surrealism. “Joans was incredibly energetic and constantly on the move in his lifetime,” Gale explains. Joans’s Long Distance exemplifies his life’s work. It is a 10m-long game of consequences – the children’s game where one player draws part of a scene and covers it for the next player to add to, and pass along for the next turn. “But this is on a mammoth scale and made over a couple of decades. There are poets and musicians, writers and political thinkers as well as artists who have contributed. Joans was the thread that brings these people together and he made it in Paris, Mali, North and Central America and London.” You can see all kinds of familiar names involved in the game including Malangatana, Dorothea Tanning, Paul Bowles, Allen Ginsberg, William S Burroughs, James Rosenquist, Roland Penrose and Jacob Lawrence.

Long Distance (1976-2005) by Ted Joans (Credit: Private collection / Ted Joans estate, courtesy of Laura Corsiglia)

It seems to bring all the most wonderful aspects of Surrealism together – the playfulness, the political commitment, the view that the movement aimed to be above creed, race or ethnicity. Gale agrees. “It embodies the fundamental idea that Surrealism was an international community.”

Surrealism Beyond Borders is at Tate Modern, London, until 29 August 2022.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.