How the first pop star blazed a trail

Think of an era-defining, wildly popular pop star: are you picturing David Bowie? Prince? Elton John? Maybe Taylor Swift, Lady Gaga or Adele? The solo singer-songwriter, whose persona is as well-known as their music and lyrics, is a cornerstone of popular music.

Yet none of those names achieved anything like the domination of arguably Britain’s first popular music star: Charles Dibdin. If the name isn’t familiar, that’s probably because he died in 1814 – although you might recognise the tune of one of his many nautical songs, Tom Bowling, often featured in the UK’s popular annual classical concert, Last Night of the Proms.

More like this:

– An album that defined the 20th Century

– Is this the greatest song of all time?

– America’s first black superstars

Yet in his own lifetime – and indeed for half a century after his death – Dibdin was no one-hit wonder, but a hugely prolific, extremely famous figure. He performed in operas and then wrote his own, composed more than a thousand songs, toured one-man shows around the country, and opened his own London theatre. He penned several novels and a five-volume history of theatre. His own autobiography also stretched to four volumes – the largest memoir of the period, and a good indication of Dibdin’s remarkable facility for self-promotion.

“He was the most dominant singer-songwriter that Britain has ever had,” insists David Chandler, Professor of English Literature at Doshiba University in Kyoto, who has overseen the recent recording of several of Dibdin’s shows for CD and digital streaming. “Who is the great British singer-songwriter? Most people are going to choose someone alive or recently deceased – but most of those would have some competition [in their respective eras]. With Dibdin, you just have someone with no obvious rival. Nobody else could combine his performance skills and his musical talents, and his facility for writing lyrics, and his ability to self-publicise, all in one. That’s what makes him really unique.”

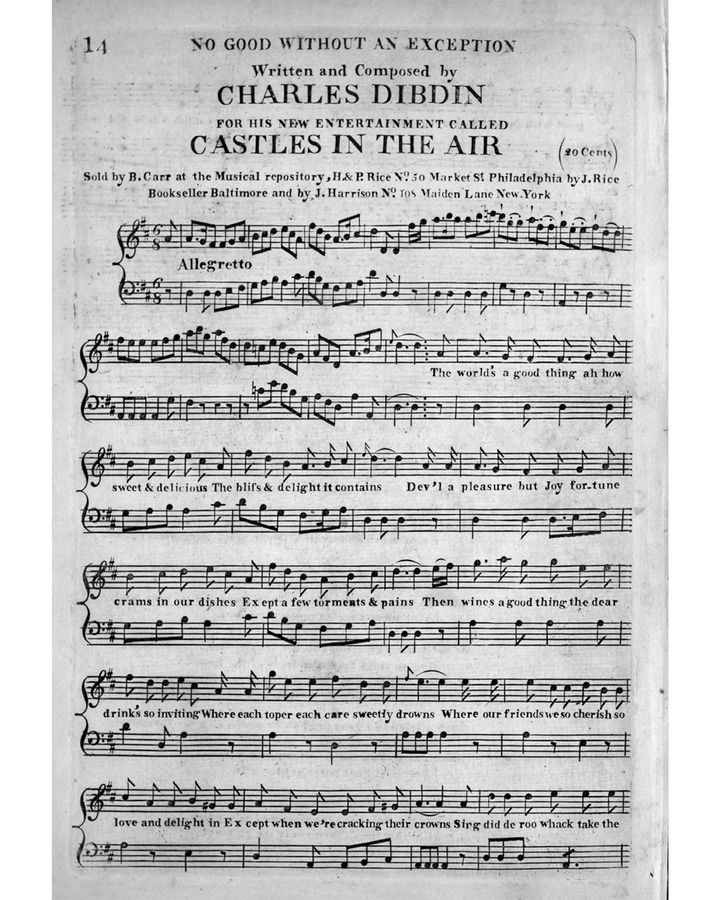

Unusually for the time, Charles Dibdin published his sheet music, which helped to popularise his songs (Credit: Getty Images)

Chandler first became fascinated by Dibdin because, as an academic researching the Romantic era, he kept tripping over Dibdin’s name in newspapers. Dibdin clearly had a rather tempestuous nature, and was often getting into financial difficulties, fighting with the critics, and falling out dramatically with other figures in the London theatrical scene – including David Garrick, who exploited Dibdin’s musical talents for his Drury Lane theatre in the 1760s and 1770s, when Dibdin was a young man.

Dibdin’s reputation as being tricky to work with ultimately led to his staging one-man shows from 1787. He called these innovative, touring performances his “Table Entertainments”, and it is a selection of these – alongside The Jubilee, a work written for Garrick’s bonanza Shakespeare festival in 1769 – that have lately been performed and recorded by Retrospect Opera, with baritone Simon Butteriss bringing Dibdin back to life.

“Dibdin made enemies, certainly, like a lot of large personalities do. And that’s why he ended up having to work on his own,” laughs Butteriss. “It was a struggle – he very much had to do everything himself, having been feted at Drury Lane.”

The Table Entertainments, however, were a hit. A charming raconteur, Dibdin would play multiple characters, blending comic storytelling with songs played on the piano. In his most successful, titled The Wags, for instance, Dibdin conjures up a villa outside of London – a “camp of pleasure” where English eccentrics eat and drink, tell jokes and stories, and sing songs. First performed in 1790, The Wags was his fourth Table Entertainment, and saw Dibdin “able to refine his product to the point where it had an almost perfect appeal,” says Chandler. Dibdin performed it 108 times in its first London season alone – and went on to churn out new Table Entertainments for the next 20 years.

“In the writing, he is so alive,” says Butteriss, when asked about the attraction of Dibdin’s work. “I do the patter parts in Gilbert and Sullivan, and character roles in opera, and because I think more like an actor than a singer, it really appealed to me that there was so much dramatic and comic meat in his writing. He felt like a kindred spirit.”

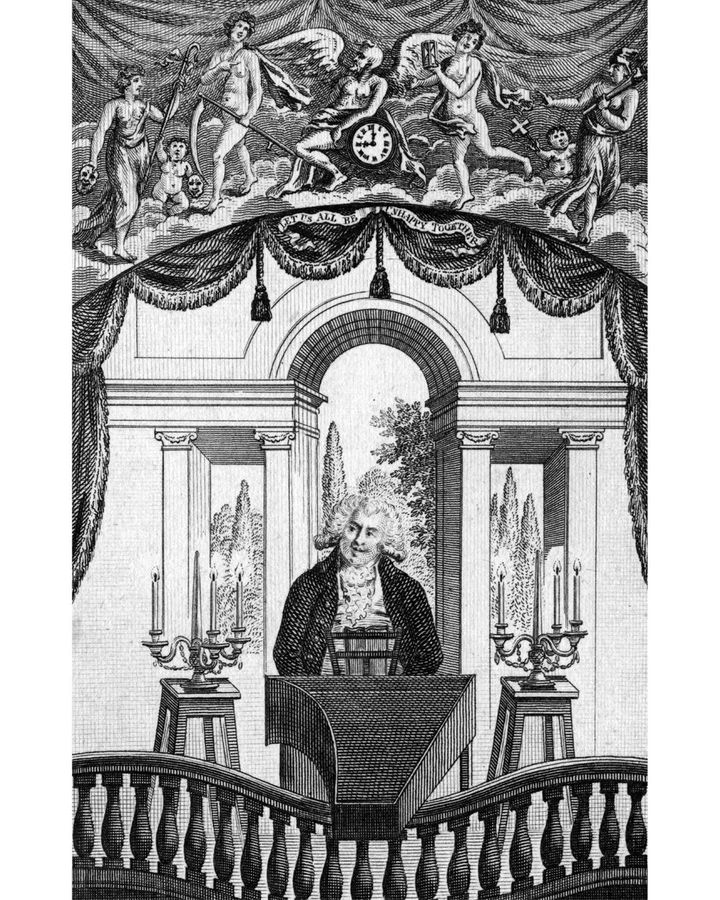

In his lifetime, singer-songwriter Charles Dibdin was hugely prolific, and an unrivalled music star (Credit: Getty Images)

While Butteriss acknowledges that many of Dibdin’s songs wouldn’t stand up as individual pieces, he suggests the narrative that Dibdin writes around them is what makes them compelling. “His characters are brilliantly written, and it’s all carefully devised so he can play all the parts – it becomes a bravura thing. There’s one song called The Margate Hoy in which he plays about 10 characters simultaneously having a conversation with one another. It’s very funny indeed – it’s this tiny, seven-minute opera on its own, really.”

Outside of the London season, Dibdin toured these shows up and down the country – another innovation. “As far as I know, no one had done this before: [touring as] literally a man and piano, and playing in a very wide range of venues,” says Chandler. “Public halls, private venues, clubs… he even did a private show for the Prince Regent.”

That’s entertainment

But key to Dibdin’s success was that his characters, stories and songs had wide appeal – they weren’t just for the upper classes. “Dibdin liked his connections to powerful people; he dedicated a book to the prince,” Chandler says, but adds that Dibdin believed he could entertain anybody: “He had a very broad cross-section of audience, that varied depending on where he was doing the show – the university towns, where you’d get an intellectual, student audience, but also northern industrial centres. He talks about farmers coming to his show.” He always enjoyed playing Liverpool, apparently, where his humour went down particularly well. And Dibdin’s comic timing, stage presence and facility for a quick-witted ad-lib were certainly all part of the brand. “His manner of coming upon the stage was in a happy style,” wrote his contemporary, playwright John O’Keeffe. “He ran on sprightly and with a nearly laughing face, like a friend who enters hastily to impart you some good news.”

You could even see Dibdin’s shows as a very early form of stand-up; there are tales of him sparring with drunk hecklers. “I think he is very much part of the history of stand-up as well,” says Chandler. Such was the success of his solo shows, Dibdin was able to open his own small theatre, the Sans Souci, in London in 1795 to host them – also an unheard-of thing for a performer at the time. “It was a tiny theatre, but it was a place people wanted to be seen,” suggests Butteriss.

Dibdin was not only a composer but also a writer – he penned several books (Credit: Getty Images)

Another of Dibdin’s canniest moves was to pioneer merchandise: he would sell his own sheet music, as well as his books, at performances. His self-publishing approach means it’s hard to tell exactly how popular his three novels really were, although we do know they appeared in more than one edition.

More significant are the song sheets, which featured lyrics and scores for keyboard and a kind of widely played flute. “One of Dibdin’s strokes of genius was to start publishing his own music, which was not at all common [at the time],” points out Chandler. “He’d sign each one – he must’ve had these enormous signing sessions.”

It was another clever innovation – not only offering audiences a chance to take away a signed memento of a good night out, but also a way to make sure his tunes were heard more widely, sung at home or in taverns. As an indicator of how numerous and widely collected his songs were, in the Bodleian Library’s collection of surviving Broadside ballads from the later 18th Century, a whopping 324 are by Dibdin – while his closest rival clocks in with only 11.

And this doesn’t take into account how Dibdin fans might themselves make copies of someone else’s score. Few such hand-written scores survive, but the practice was likely common – and we know it took place with Dibdin’s work thanks to one very high-profile fan: Jane Austen. Her small music collection features several works by Dibdin, copied out in her own hand.

She’s not the only Dibdin acolyte: he’s also thought to have been a major inspiration for Gilbert and Sullivan. “Dibdin invented the English comic opera that they then developed,” says Butteriss.

Dibdin’s operas were enormously popular not only in his lifetime, but throughout much of the 19th Century, and we know WS Gilbert saw Dibdin’s work as a young man. Butteriss thinks his influence is explicit. “[Gilbert] lifts the comedy naval language he puts in HMS Pinafore from Dibdin. And I think the audience would have recognised it – a homage, rather than a stealing.”

Two of Dibdin’s most successful operas, The Waterman (1774) and The Quaker (1775), were performed all over the anglophone world – and in Britain continued to be performed for up to hundred years afterwards, says Chandler. “Which is incredible: no other opera of this period had such a long afterlife as those.”

The singer songwriter – shown here on stage at the Sans-Souci theatre – was a virtuoso performer of his own works (Credit: Alamy)

Both Butteriss and Chandler would love to see his full-scale operas remounted – but we no longer have the original orchestral parts. Those that do exist, for The Waterman for example, hail from those productions from the mid-19th Century. How close these are to the originals is unclear – although they’re potentially interesting in their own right. The 1840s – several decades after Dibdin’s death – proved to be the peak moment for his legacy. As well as his operas still being staged, there was also a flush of interest in his songs, with numerous new editions published, including one ambitious collection by Charles Dickins’s father-in-law, George Hogarth.

And then… a gradual fade into relative obscurity. A version of The Waterman was performed in Covent Garden in 1911. Another opera, Lionel and Clarissa, was revived at the Lyric Theatre in London in 1925. And people continue to record Tom Bowling to this day… Still, it’s a sharp decline from Britain’s most prolific and popular singer-songwriter to being remembered for one tune only.

So can Dibdin’s afterlife tell us anything about what we might expect for the reputations of the pop stars of our own time – what afterlife we might anticipate for David Bowie, or Adele? Well, perhaps.

“For a whole generation after his death, Dibdin was really current, a lot of his songs were known,” points out Chandler – as we now see with the most popular music of the 20th Century. “There was about 60 years where a lot of English people would have known a number of Dibdin songs. But by the time you get to 80 years after his death, he’s fading. So much new stuff comes along, some of the old just has to get displaced.”

Whether such a fate awaits pop stars in an era of Spotify remains to be seen. But as Dibdin proves, fame can be a fickle mistress – and there’s no guarantee that being the most popular figure in one era means you’ll be remembered in another.

Charles Dibdin’s The Wags, The Jubilee, and Christmas Gambols are available on CD and streaming platforms; retrospectopera.org.uk

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.