The paintings that reveal the truth

Portraiture’s growing importance was solidified in the 17th Century when the French Royal Academy created a hierarchy of genres and placed it second only to history painting. The assumption was that it would document the great and the good, and thus serve as an accompaniment to the highest of all genres. This newly designated role for portraiture was behind the formation of the earliest portrait galleries, such as Charles Willson Peale’s Gallery of Illustrious Personages which opened in Philadelphia in the 1770s, and featured many figures who had signed the Declaration of Independence. The UK’s National Portrait Gallery followed in 1856 with the very first work to enter the collection being a portrait of William Shakespeare.

Although these galleries only collected portraits of those they considered to be notable, with all the class, sex and race biases that this inevitably involved, outside their walls the genre was becoming ever more diverse. As the 19th Century progressed, portraiture became increasingly associated with the rising bourgeoisie. Their perceived vanity was mocked by many writers and critics but the rise in this form of portrait was indicative of the major social and political changes sweeping throughout western Europe, which saw the middle classes gaining more power and influence as monarchs were forced to bow to the authority of parliaments. The advent of photography was an important factor in democratising who could be portrayed but so too were changing views about the roles of individuals in society. Artists themselves played a major part in deciding who was worthy of depiction, boldly challenging social conventions as they did so.

The self portrait has of course also been an important part of artistic expression. Van Gogh’s iconic Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear, painted after he cut off part of his ear following an argument with Gauguin, is a powerful demonstration of his determination to continue painting despite the trauma. It takes centre stage at the Courtauld’s current exhibition of his self-portraits.

‘Fellowship of human beings’

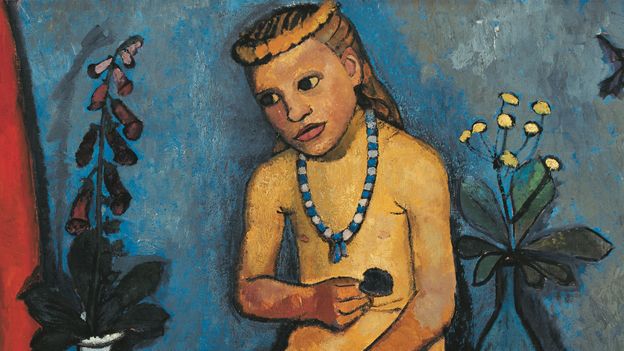

Paula Modersohn-Becker, recently the subject of a major retrospective at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, also famously made herself the subject of her portraits, along with other women, children and the local peasantry. Influenced by the Fayum mummy portraits which she discovered in Paris around 1905, her portraits have a psychological intensity rare in depictions of women at the time. Although her choice of models was at least partly down to convenience, she nevertheless treats the humblest of subjects with the utmost dignity. “They were the poorest in society and she gave them an air of timelessness, almost holiness,” says curator Ingrid Pfeiffer.