The powerful paintings reframing black experience

Consider the human figure. Not a huge ask given how much of modern life revolves around taking stock of our image: from time whiled away in front of the mirror – the average Briton, it was reported in 2016, spent nearly five hours a week in the company of their own reflection – to time devoted to burnishing our online avatars. Reaching further back – dispensing with reflective surfaces and social media feeds entirely – and the human figure still emerges as one of life’s central preoccupations:an object of carved reverence and expression for the Ancient Egyptians, a site of radical experimentation for the Impressionists of 19th-Century Europe. Figuration – the depiction of the human form as derived, in one way or another, from reality – has yoked life and art together, our bodies keeping the score and telling our stories. But the question of which bodies and whose stories have been deemed worthy of consideration – and why – is a central one.

More like this:

– The WW2 trauma that inspired Yoko Ono

– What the purple dress in Oprah’s portrait means

– 10 of the most iconic portraits from a lost US

Taking up the charge, in the here and now, of reconsidering the figure – and reckoning with figures long unconsidered, othered and erased by the art world – is The Time is Always Nowat London’s National Portrait Gallery. The exhibition gathers the work of 22 contemporary black artists who have made the black figure the object of their concern in order to “illuminat[e] the richness and complexity of black life”.

The Time is Always Now is an exhibition exploring black figurative art of the 21st Century – pictured, 1975 (8) (2013) by Noah Davis (Credit: National Portrait Gallery)

Ekow Eshun, curator of The Time is Always Now, approached the National Portrait Gallery with the concept for the show in 2019. Since then, the effects of the marginalisation of black people have gained considerable coverage. Writing in The New York Review of Books in October 2020, amid the renewal of the Black Lives Matter movement following the murder of George Floyd, Gary Younge observed there is – within the arena of racial subjugation and exclusion – “the violence that is inflicted and the violence that is implied… operat[ing] not separately, but in concert”. Similar sentiments were expressed in the wake of earlier periods of civil unrest and instances of black resistance – these crucibles of direct action brimming with myriad experiences of, perspectives on, and aspirations for black life. The overspill of some of the most resonant of these resistance movements has often been channelled into art, hence the Black Arts Movement in the US emerging during the advent of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, and the British Black Arts Movement following the uprisings – in cities including London, Bristol and Liverpool – of the early 1980s. So, what is it about this particular moment in time that has made The Time is Always Now imperative?

“We’re in a moment of extraordinary flourishing [with regard to] black artists working in figuration,” Eshun tells BBC Culture. “I wanted to mark this moment, but also to say – with an emphasis on the ‘always’ [in the show’s title] – black artists, black audiences, black people have always been in a conversation about the nature of black living.”

The exhibition takes its name from a line in a 1956 essay by James Baldwin – the phrase being preceded in Baldwin’s writing by another maxim: “the challenge is in the moment”.

“The amount of world-leading artists that are working and have worked with extraordinary skill, ambition, creative reach, imagination – it’s really tremendous,” says Eshun. “And [this] work comes out of a lattice of associations – of histories, of relationships – to previous generations of black artists, and also to the art history of the West as a whole. So, I wanted to think about how these artists are interrogating the past, while simultaneously exploring the texture of the present.”

The work of Nigerian-born, LA-based Toyin Ojih Odutola is featured in the exhibition (Credit: National Portrait Gallery)

With three thematic strands – “Double Consciousness”, “Persistence of History” and “Our Aliveness” – the exhibition traces where “now” and “then” come into contact. Within the exhibition catalogue, the contours of black intellectual theorising, political organising and image-making are explored as far back as the late 19th Century, when leading African-American sociologist W E B Du Bois popularised the term “double consciousness”. The exhibition itself, though, only features work created from 2000 onwards. This means missing some of the classics of the genre such as Kerry James Marshall‘s Invisible Man (1986) – a personal favourite of Eshun’s – or Howardena Pindell’s Autobiography: Water (1988).

However, the strict starting point does make for incredibly focussed curation. As Eshun tells it, one of the rewards of working with this threshold was finding he did not need to “impose” interpretative readings nor reverse-engineer relevance across the widest sweep of black art history; the more precise the span of time covered, the more “threads and affinities” between works and themes surface unforced. “I just wanted to think about how the act of figuring the black body opens up a number of different territories and perspectives,” he adds.

Standout works featured in the exhibition include those by US artists, such as Amy Sherald and the late Noah Davis, along with the Nigerian-born, Los Angeles-based, Toyin Ojih Odutola. If there is a common thread to be unpicked between Sherald’s A certain kind of happiness (2022), Davis’s 1975 (8) (2013), and Ojih Odutola’s A Grand Inheritance (2016) it would be their zeroing in on the black figure at ease. With Sherald and Ojih Odutola, this takes the form of figures in static, solitary repose: the young woman portrayed in A certain kind of happiness – rendered in Sherald’s signature grisaille – looks straight ahead at the viewer, appearing to take the measure of them as much as they would her, with a gentle smile and arms in the balletic bras bas position; meanwhile, the young man portrayed in A Grand Inheritance is comfortably splayed across an armchair – a sumptuous composition replete with Odutola’s rippling, multi-tonal mark-making, entirely unbothered by the gaze that falls upon him.

She was learning to love moments, to love moments for themselves by Amy Sherald (2017) (Credit: Amy Sherald/ Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth/ Joseph Hyde)

Davis takes a contrasting approach to capturing the spirit of black relaxation – and, in doing so, opens up an entirely different territory and perspective on the subject: 1975 (8) depicts a scene of black sociality, inspired by photographs taken by Davis’s mother in the 1970s on Chicago’s South Side. An outdoor swimming pool offers the black figure a stage to present how time might be whiled away in the company of others. In the foreground is the arched figure of a young black diver – heels to the heavens – not yet submerged; in the middle distance and background is a throng of black figures enjoying the water and proximity to one another.

This is a communal space enlivened by the black figure. It is also a space established –presumably – as a result of the US segregation of municipal swimming pools, which was only glacially eroded following the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. As such, what Davis also conjures in the unseen outer edges of 1975 (8) is all that has been – all the anti-black violence inflicted and violence implied, that should never have been.

‘Imagining from scratch what might be’

Arguably, few other works featured in The Time is Always Now attend to what Eshun describes as black figuration “imagining from scratch what might be” more than those by British artist, Kimathi Donkor. Speaking to BBC Culture, Donkor revisits the path that brought him to artistic figuration.

“I think one of the things about making pictures for me has always been, I suppose, to do with the difficulty of speech,” he begins, before righting himself, “Well, actually, I don’t have difficulty speaking – I can talk the hind legs off a donkey! But, I suppose, I was quite interested in comic books [as a child]. When I first told myself that I wanted to be an artist, it was because I wanted to be a comic book artist. The idea of being able to tell the stories through pictures – and to hold a certain symbolic significance within particular images – was quite important to me when I was young. And so that relationship between narrative and imagery has always been really powerful.”

Nanny of the Maroons’ Fifth Act of Mercy by Kimathi Donkor echoes High Renaissance style (Credit: Kimathi Donkor/ Courtesy of artist and Niru Ratnam/ Tim Bowditch)

Donkor was born in 1965 in Bournemouth to parents of Anglo-Jewish and Ghanaian heritage, before being adopted into a family of mixed British and Jamaican descent. He went on to spend his formative years in the UK and Zambia, this cross-continental living kindling his early love of the diversity of what could be configured as art, from comics to the works of artisans of the Kingdom of Kush and Tutankhamun’s gold funerary mask. He then studied for a Bachelor’s in Fine Art at Goldsmiths University in South London. “I found it quite a difficult experience for a variety of reasons,” Donkor says of his undergraduate years. “I think one of them was to do with the political awakening that had been occurring within me for quite a while before I went to university.”

The 1980s were marked by profound disaffection and deep pain for scores of black Britons. The long arc of “complex political, social and economic factors” – as it was put in the Scarman Report of 1981 – resulted in frustrations, and the social order fracturing, in cities across the nation, from London to Leeds. Donkor found himself, at this time, pulled toward black community organising and the spaces where art interfaced directly with issues of the day, joining the discussion forum Black History for Action and, later, designing flyers for the Black People’s Campaign for Justice. However, the curriculum at Goldsmiths – which was, at the time, “overwhelming[ly] Eurocentric” – was not conducive to the parallel development of political principle and artistic practice.

Donkor did, eventually, find tutors who allowed him to “feel validated in [his] interests”, including the academic Sarat Maharaj and sculptor Pitika Ntuli – both of whom had found ways to situate their backgrounds (Indian South African and amaZulu South African, respectively) and commitment to anti-Apartheid activism within their work.

This newly minted sense of validation was parlayed into a successful appeal, led by Donkor and a cohort of like-minded peers, to the faculty at Goldsmiths to commission a group of then-emerging black artists to deliver a series of modules at the university. One of Donkor’s fellow students was Mark Sealy, now Director of Autograph ABP; and one of the emerging artists commissioned was Sonia Boyce, who became the first black woman to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2022 and went on to win the Biennale’s most prestigious award, the Golden Lion, that same year.

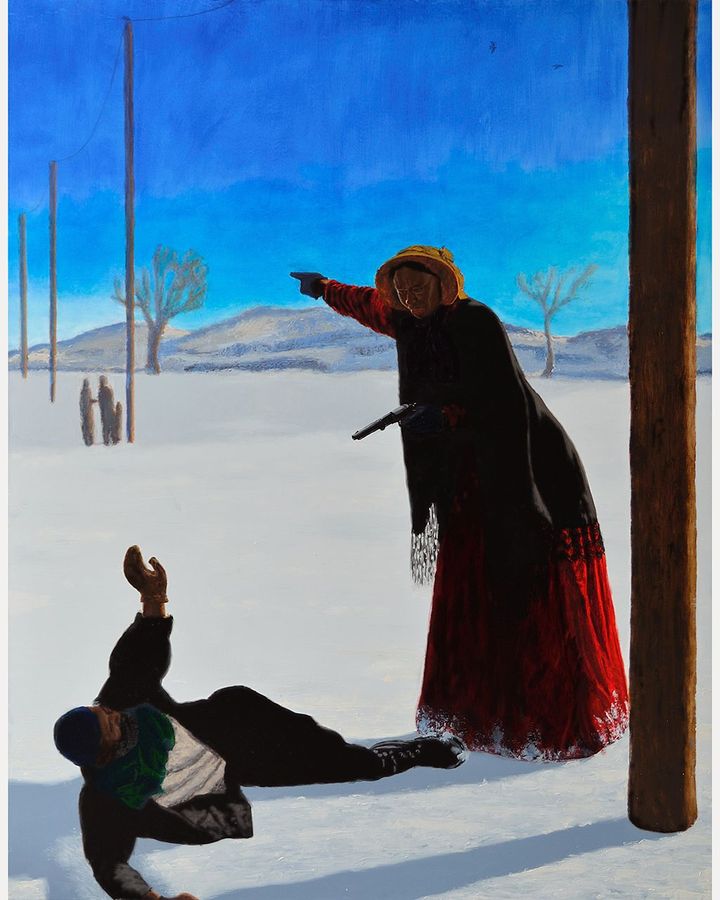

In Harriet Tubman en route to Canada (2012), Kimathi Donkor envisages a scene from the life of the abolitionist (Credit: Courtesy of artist and Niru Ratnam/ Tim Bowitch)

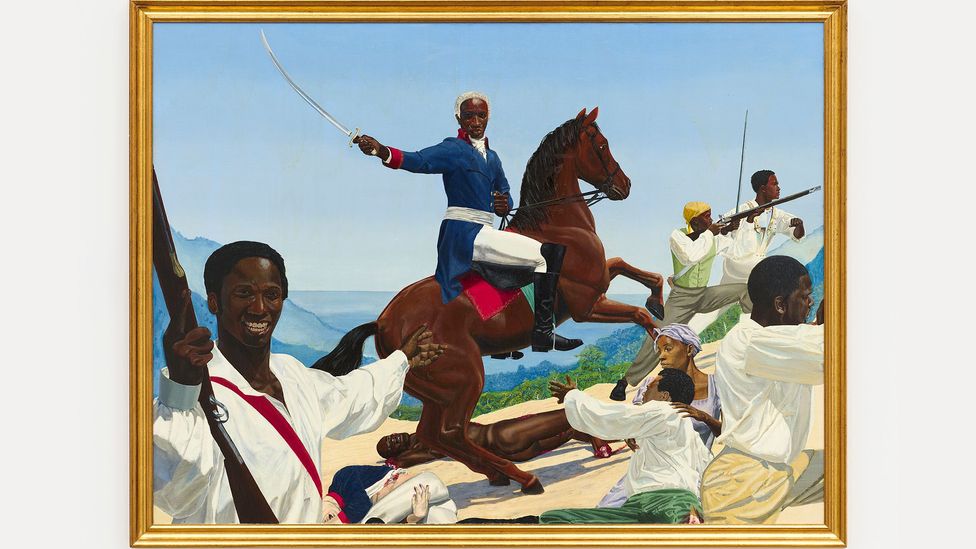

Seeking “emotional truth” in the face of a lack of available “details” has been a strong motivation, says the artist. Donkor’s Nanny of the Maroons’ Fifth Act of Mercy (2012) is an arresting work of figuration depicting the much-revered Nanny of the Maroons (or Queen Nanny), an 18th-Century rebel leader of the Jamaican Maroons. While it harks back to the Grand Manner artistic tradition through its composition – Queen Nanny’s silken garments, all billowing sleeves and a swathe of green and gold, along with her look of sobering equanimity are hallmarks of this High Renaissance style – Nanny of the Maroons’ Fifth Act of Mercy ultimately registers as a postmodern fable of black sovereignty and sacrifice.

“There’s not much documented in the records [about Queen Nanny],” Donkor explains, “But what we can glean from what is [present is that] she was a very powerful, charismatic, determined, strong, resilient, courageous and clever person. She was able to force the British Army into a truce, and negotiate an autonomous area of Jamaica during the [period of] slave colonisation [for] a refuge community of the Maroons.”

Armed with these “bare facts” about Queen Nanny, Donkor began to think about the kinds of image and allied narrative that could be assembled from the archival record, as well as that which could be retrieved in the absence of certain details. “What kind of dramatic impact might she have made on Jamaican society? And how might that relate to the story of art in Britain, and to the story of British artists and their dependence upon slave-produced wealth?”

This approach is also known as “critical fabulation”, a method developed by cultural historian Saidiya Hartman. It is a form of speculative address that emphasises the “figurative dimensions of history”, by leaning into both the extant historical record and that which was left unrecorded, so as to relay “an impossible story and amplify the impossibility of its telling”.

“In my painting of Queen Nanny, the face of the woman is my wife, [Risikat] – she modelled for me. But the figure [itself] is actually drawn from a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds called Portrait of Jane Fleming,” Donkor shares. “Fleming [later Countess of Harrington] came from a family that was deeply involved in enslavement – specifically in Jamaica, but also other Caribbean islands – and her stepfather was a very wealthy plantation owner. When she got married, one of the first things she did was she financed her husband to take a regiment of soldiers to Jamaica as part of a garrison there. That’s how rich she was. So, I just thought there was a really strong relationship between this aristocratic, English woman; between the Jamaican slave plantation; and between Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts… And that [figuring Queen Nanny through these relationships] would be the perfect fit: a way of reappropriating some of that cultural wealth, which had been essentially stolen and ‘slave-washed’ into a beautiful painting [originally by Reynolds].”

Donkor seeks ’emotional truth’ in his work – pictured, Toussaint L’Ouverture at Bedourete (2004) (Credit: Courtesy of artist and Niru Ratnam/ Tim Bowitch)

Donkor is still drawn to beautiful images, though. He has two daughters, aged three and seven, and since becoming a father has found himself “very taken by the amazing flourishing of illustration, particularly illustrated books for children of African heritage”. The diptych, Descending a Dune (2020) and The Hikers (2022), hangs behind Donkor as we speak on our video call: sherbet-hued scenes of gently sloping valleys and unguarded copses – an idyll – dotted with serene black figures. They seem to exist outside of time itself. And so, time – and how Donkor balances time across his artistic practice and his role as course leader and interim programme director of Fine Art at Camberwell College of Arts – is the topic we alight on.

“You get to a stage as [an artistic] practitioner where a lot of things are second nature or very obvious, but when someone’s just starting out they’re completely oblivious to it. And so it’s really joyous [in having an academic career] to be able to say to somebody, ‘have you thought of this?’ or ‘have you seen that?’ or ‘have you tried this?’ And then, they might say ‘oh, I can see how this works’ or ‘well, no, that’s not for me’. But, either way, just to be able to help expand people’s horizons,” Donkor concludes, with a smile, “And, in that sense, [teaching] does have a similarity to working as an artist, because I suppose that’s kind of what we do. We open up a [field of] vision for people that they hadn’t previously experienced.”

The Time is Always Now is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, until 19 May

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.